When the 2021 college football regular season ended in November, Eli Boettger wondered for AthleticDirectorU whether college football had an attendance problem. His conclusion? “Pandemic or not, college football attendance — as well as many other collegiate and pro sports — has witnessed steady decreases over the last decade.”

If attendance is a proxy for college football viewing demand, so, too, would be television ratings. An inverse relationship exists between attendance and ratings because, by all accounts, 2021 was a good year for football on television. And, if fans are reticent about attending games in person during a pandemic, watching on television would be a good substitute.

I wrote in October 2021 that early season college football ratings were mostly good news for college athletic administrators and their media partners. “Demand for marquee college football games through week six is booming as evidenced by the number of games watched by more than four million viewers.”

That trend continued through the season with Michigan-Ohio State recording an 8.1 rating for a noon Eastern kickoff in late November, the most-watched regular season game in two years. Even Army-Navy returned to pre-pandemic ratings with a 4.2.

As we hit bowl season this past December, a new narrative around college football began to emerge; the playoffs needed to expand because the semifinal games were not competitive. Wrote Chris Vannini in The Athletic, “It’s why the format must expand again. Not to produce different champions, but to give us competitive, meaningful games and change the ultimate goal of the sport.”

Vannini advocated for a 12-team playoff, which would produce eight additional games, four round-of-12 games and four quarterfinals. Ignoring the increased expenses related to more teams playing multiple post-season games, and the associated challenges with end-of-semester finals and holiday travels, Vannini’s assertion that the “CFP has pulled off the remarkable feat of failing to give us good semifinal games while also devaluating the New Year’s Six games outside the CFP rotation” is without merit.

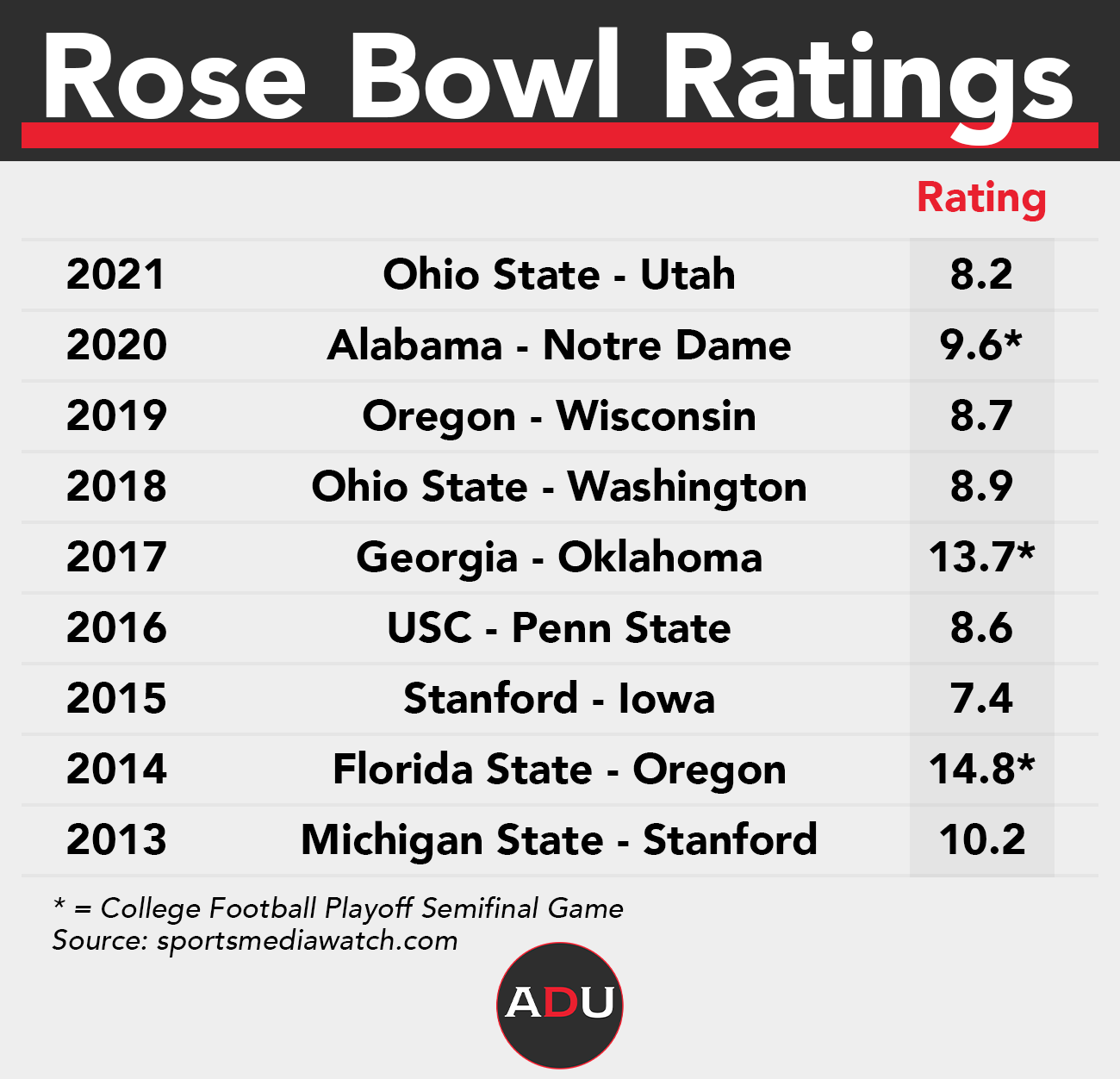

Consider the inference in his thesis that additional playoff games would increase demand via higher television ratings. The 2021 Rose Bowl between Ohio State and Utah, teams which finished the year ranked 6th and 12th, respectively, drew an 8.2 rating, just below the Alabama-Cincinnati semifinal game which recorded an 8.6. Would OSU-Utah as round-of-12 game attract sufficiently more viewers than if it were a non-playoff Rose Bowl? That seems unlikely.

In fact, looking at data since 2013, the final year of the Bowl Championship Series, through 2021, non-semifinal Rose Bowl ratings range from a high of 10.2 in 2013 to a low of 7.4 in 2015. The past four non-semifinal Rose Bowls, presumably between teams that would be in a round-of-12 game, averaged an 8.6 rating, exactly the same number as this year’s semifinal between Alabama and Cincinnati. The Rose Bowl, as a New Year’s Six bowl, has not been devalued because of the CFP.

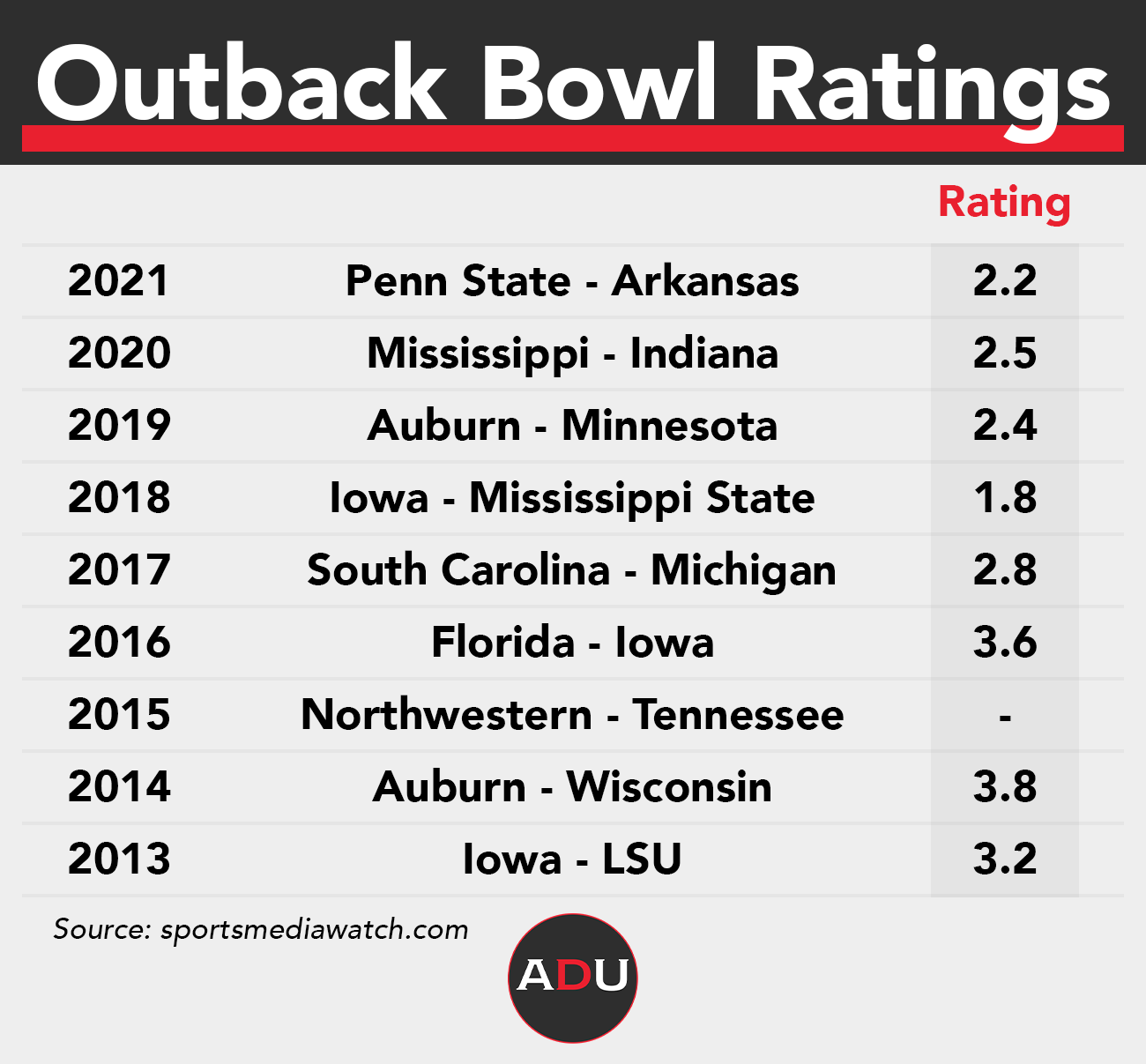

Perhaps a better comparison for a round-of-12 game would be a non-marquee New Year’s Six bowl game – say, the Outback Bowl. This works for a couple of reasons. First, the Outback Bowl kicks off early, in the noon Eastern window. An expanded College Football Playoff would almost certainly have a noon kickoff, particularly since, at the end of December and early January, the CFP is still competing with the NFL, meaning Sunday is not a viable broadcast day. So, a Friday night/Saturday tripleheader is more likely, and that would assuredly involve a noon kickoff.

The second reason the Outback Bowl is an appropriate comparison is that it annually features teams from the Big Ten and the SEC, the two conferences that dominate college football attendance and ratings. It is reasonable to assume that college football fans would be interested in a bowl game such as the Outback Bowl, featuring top teams from the top conferences.

Not so fast, my friend.

Once again using data from 2013-2021, we see the Outback Bowl averages a 2.8 rating over eight years. The 2015 game between Northwestern-Tennessee did not have a rating. This year’s game between Penn State and Arkansas drew a meager 2.2, behind several non-New Year’s Day bowls as well as the Citrus Bowl between Kentucky and Iowa, schools from the SEC and Big Ten, respectively, which kicked off at 1:00 Eastern on New Year’s Day. If anything, the trendline for the Outback Bowl, as shown in the table, is not good.

Is it possible the Outback Bowl is devalued? Maybe. But, probably not. As Matt Brown wrote last month in his Extra Points newsletter, “the 46 games played during the 2021 season between programs that rank in the top 25 in all-time winning percentage among Power 5 programs, plus Notre Dame, received an average rating of 2.85.”

The Outback Bowl’s 2.8 average rating does not differentiate it from games featuring college football’s winningest teams. So why is it lower rated than the Rose Bowl? Tradition? Is it the early kickoff? Is it the matchups? Or, is it the fact it does not have an exclusive broadcast window? This year’s game competed head-to-head with the aforementioned Citrus Bowl and the Fiesta Bowl between Oklahoma State and Notre Dame. Perhaps the New Year’s Six bowl games are cannibalizing one another, rather than being devalued by the CFP.

What does this portend for a round-of-12 college football playoff game that kicked off at noon Eastern? I’m guessing it would have more interest than the Penn State-Arkansas game. But how much? As we learned from this season, fans will seek out a game of interest regardless of kickoff time (e.g. Michigan-Ohio State). Plus, the assumed exclusive window would heighten viewership as well.

When to stage these games is another question. Using this season as a guide, and seeking to keep the semifinals on December 31, the round-of-12 games could have been December 17-18 with the quarterfinals December 24-25. The NFL had game windows on December 18 and December 25 so if avoiding direct competition with the NFL is a goal, this will not work.

As a result, it is not unreasonable to consider games competing head-to-head with one another for viewership. That is not ideal for viewership either. This year’s Citrus Bowl recorded a 3.5 rating while the Fiesta Bowl notched a 4.2. Could we expect an exclusive game to draw a 6 or 7 rating, creating more value for the CFP and its media partner? More games does not automatically equate to increased demand, or better ratings.

Additionally, Vannini argued that by including more teams in a playoff, fewer players will opt out of the bowl game. He cited two star players opting out of the Peach Bowl matchup between Michigan State and Pittsburgh as an example of something that would not occur in an expanded playoff. And while that could be true, it hardly impacted the demand or watchability of the game. The Spartans scored 21 fourth-quarter points to rally and win, 31-21, in a game that drew a 4.0 rating, the seventh-highest among bowl games.

He also cited two Ohio State receivers opting out of the Rose Bowl as something which would not have occurred with an expanded playoff. In the end, the Buckeyes did not need the two players to rally from a 38-28 deficit to win 48-45 in the most watched non-CFP bowl game.

Player opt-outs do not appear to devalue bowl games by decreasing television demand.

To be certain, college football has challenges. The declining in-stadium attendance should alarm athletic directors. The transfer portal has changed how coaches recruit by providing athletes with agency over where they play. Conference realignment always seems to be in motion. Astronomical coach buyouts have justifiably brought criticism upon the sport.

Increasing the number of teams in the college football playoff will not solve any of those challenges. If anything, it has the potential to further devalue the regular season, leading to continued decreases in attendance. It could heighten transfers as players seek to align with “win now” programs. An increased number of teams, and what conferences, if any, get automatic qualifiers, could lead to further realignment and possibly create “super conferences.”

And, it could increase pressures on coaches to be one of 12 teams in the playoff. Winning records and being doused with Duke’s Mayo may no longer be sufficient to save a coach’s, or an athletic director’s, job.