In the span of little more than two weeks last August and September, three Division I schools – Iowa, William and Mary, and Minnesota – announced, collectively, they were cutting 14 non-revenue, or “Olympic,” sports. While all but six of those sports have subsequently been reinstated, at least temporarily, the cumulative shock waves of sports cuts at high-profile schools (e.g. Stanford, Michigan State, Clemson) were enough to serve as a catalyst for the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) and its own Collegiate Advisory Council (CAC) to form a collegiate sports sustainability “think tank.”

On Monday, in what appeared to be a carefully scripted and controlled environment, the initial work of the USOPC College Sports Sustainability Think Tank was presented in a virtual “town hall,” which did not involve any interaction with the virtual audience despite the encouragement of questions and several posed in the Zoom chat.

Positioned as “a first-of-its-kind effort to convene leaders from across the collegiate and Olympic and Paralympic landscapes to ideate around keeping sports in our country strong,” the Think Tank is chaired by University of Florida athletic director Scott Stricklin. It includes many prominent Division I athletic directors, conference executives, NCAA personnel, NGB executives, and the occasional athlete or coach.

Kevin White of Duke acknowledged in the opening remarks that these were the “two best teams in the world,” referring to the USOPC and college athletics. Stricklin said in reference to the United States’ education-based sport system that it was the “envy of the world,” in part because the USA won more medals, 121, than any other country at the most recent 2016 Olympic Games. This emphasis on winning seemed to contradict the message from a pre-Zoom call slide of a Pierre de Coubertin quote, “Olympism advocates for broad-based athletic education accessible to all… serving as an engine for national life and as a basis for civic life.” (Italics added on USOPC slide). In many ways, the Olympic movement and college sports live parallel existences, espousing ideologies of the role of athletics in overall education, but rewarding and emphasizing performance and winning.

Since the NCAA’s origins in the early 1900s, college athletics and the Olympic movement have been intertwined. College athletics provides athlete development for Olympic athletes at little to no cost to the Olympic world, but with little revenue in return to the college athletic world. Now, with colleges dropping Olympic sports, a reckoning of sorts is facing the USOPC. Monday’s presentation proved to be a way to keep the dialogue in front of select decision-makers in both spheres at a time when the USOPC is facing Congressional pressure to reform through the Empowering Olympic and Paralympic Amateur Athletes Act.

The group of speakers shared information about three strategic concepts which emerged from “robust discussion in the fall of 2020.” From these concepts, the group will further identify actionable recommendations this spring. While little actual news was disseminated in the “town hall,” some points were raised which suggest what the Think Tank is thinking.

Chris Plonsky of Texas and Rob Mullens of Oregon, who will serve on the EOPAAA committee, spoke first on the concept of sports sustainability, which is defined on the USOPC site as the need for “more flexibility to manage sport-specific expenses and generate revenue in a cost-effective manner.” In particular, Mullens stressed the importance of creating sport-specific rules around recruiting to help alleviate costs, while Plonsky mentioned collaboration with local youth programming. Decreased expenses and grassroots involvement are positive developments which would benefit Olympic sports.

Next up were the Ivy League’s Robin Harris and Ohio State’s Gene Smith speaking on collaborative sport structures between college athletics and National Governing Bodies. “We need to connect college sport leaders with NGBs. They do not work together,” Harris said. For anyone involved in the administration of Olympic and/or college sport, that statement is not a surprise. I have noted previously in this space that college sports and the USOPC do not support one another, and never really have, despite positive public relations statements suggesting “85 percent” of 2016 Team USA competed collegiately.

The third concept was vertical partnerships as presented by North Carolina’s Bubba Cunningham and California’s Jim Knowlton. This discussion actually produced some tangible ideas, including possible NCAA/NGB events which, as Knowlton said, could “make championships more exciting.” The sentiment here was about using shared expertise to reduce costs and support broad-based sport sponsorship, a buzzword used both in collaborative sport structures and vertical partnerships. The Think Tank microsite specifically states it “strongly supports sustaining the sport sponsorship minimum at 16.”

But why even mention that number, 16? Is there consideration by FBS schools to lower that number? Clemson’s decision to drop three sports effective June 2021 gets it to the floor of 16 sports for next year. Mississippi State was already at 16. Would these schools, and others perhaps, go down further if given the opportunity?

And this encapsulates the biggest problem I have found with the Think Tank, and that is they are not thinking about anything but FBS, or, more specifically the Autonomy 5. That arbitrary number of 16 sports only applies in FBS.

There are no administrators from FCS schools, D2 schools, D3 or NAIA schools in the tank. What good is it to have a College Sports Sustainability Think Tank if you are not going to think about ALL college sports across ALL levels.

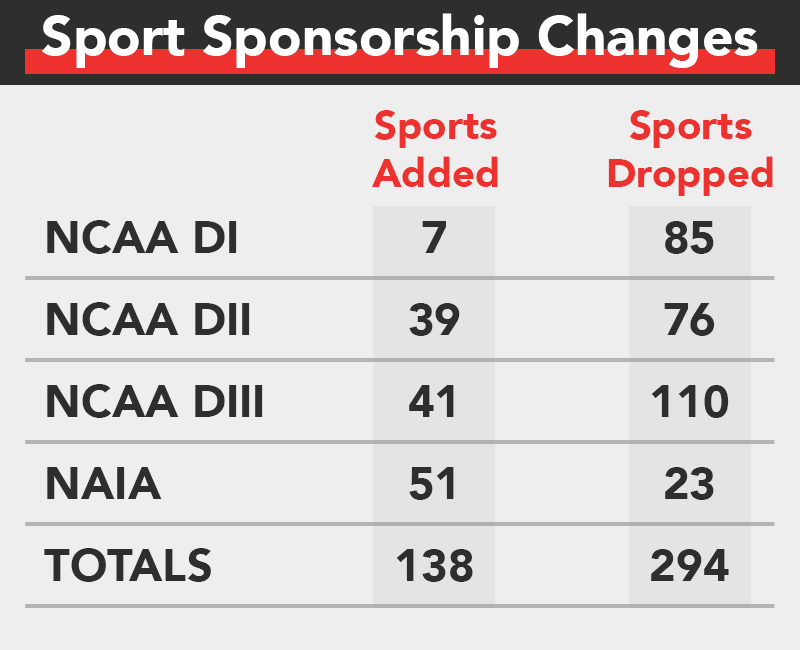

In fact, the whole purpose of the Think Tank appears to be about preserving the relationship between the USOPC and FBS schools. Perhaps that is appropriate since, according to my research, D1 schools have dropped 85 sports since the pandemic, while adding only 7. (That link is to a Google Sheet with tabs for different divisions as best as I have tabulated.) Clearly, the ratio of sports dropped to added is most pronounced in D1, making sustainability at the level a concern.

If we really wanted to think about the direction of Olympic sports in the college athletic space, we would turn to D2, D3, and NAIA where sports such as wrestling, volleyball, triathlon, and swimming have all seen growth. Ten new women’s wrestling have emerged since the pandemic. Exactly ZERO of those have occurred at D1. Men’s volleyball? Up 9 programs, only one in D1.

So, why the focus on D1 and FBS? If few or no D1 schools sponsor women’s wrestling or men’s volleyball but many D2 or NAIA schools do, those institutions should become the strategic partners for the USOPC. If so, more D2 and D3 schools could look to add sports like women’s field hockey, women’s triathlon, men’s volleyball, and women’s wrestling. But what incentive exists for those institutions to do so if they do not have a seat on the Think Tank for their thoughts to be heard?

Within vertical partnerships, Alabama’s Greg Byrne and the Big East’s Val Ackerman discussed the need for elevated recognition of Olympic sport athletes with Byrne suggesting a “broad appetite for the untold story” of Olympic-sport athletes existed. They mentioned the various platforms available to all university athletic departments, citing the networks owned by the Autonomy 5 conferences, but also acknowledged the problem of having Olympic sports rights bundled with football and basketball. Byrne still believed opportunities exist to highlight non-revenue sports. “Everyone has social media,” he said. Ackerman spoke of elevating awareness and recognition of these sports. “It is an opportunity to promote and amplify Olympic sports,” she said while alluding to a possible recognition of a campus contribution to Team USA.

And that’s great, but my question is why are athletic departments not doing this already? It is not like Instagram and Snapchat are startups created in the last few months. If Autonomy 5 schools really wanted to draw attention to Olympic sports, it seems they already have the platforms in place to do it.

Let’s engage in a hypothetical exercise to test the value of that branding opportunity should a D2/D3-NGB partnership emerge. As I mentioned, I think a solution exists in which a handful of D2 or D3 campuses emerge as THE places to go for an aspiring Olympic wrestler or field hockey player or gymnast. Details would need to be worked out, of course. However, I could see how it helps the individual institution through increased exposure and financial resources. Similarly, I could see how it helps the USOPC by being able to influence the coaching and training of athletes.

And, let’s be honest, Olympic sports would also benefit from a promotion and exposure standpoint by escaping the 300-pound gorillas of FBS football and men’s basketball programs which dominate resources and media attention.

The most disappointing things about Monday’s “Town Hall” were the lack of interaction with the audience and the scripted, almost sterile, nature of the presentation. Questions were asked in the chat regarding the role of Paralympic athletes in the Think Tank. A question about Title IX implications was also raised. These were not acknowledged at the time despite the anticipation some Q&A would take place. Instead, a few questions submitted ahead of time by unknown parties were “tossed” to designated responders who answered in a scripted fashion.

So while it is true that 121 medals dwarfed runner-up China with 70 medals, an argument could be made the gap will shrink dramatically in the future if the USOPC only devotes resources to sports contested at the collegiate level. The IOC is increasingly seeking to appeal to a younger audience. With the addition of sports such as breakdancing, skateboarding, climbing, and surfing to the 2024 Olympic program in Paris, the ability for the USOPC to excel will require it to look at resources beyond college sports. Of the 32 sports in Paris, only 16 – exactly HALF of the 2024 Olympic sports – have NCAA-sanctioned national championships.

Or, perhaps the solution will be for college athletic departments to begin sponsoring breakdancing teams. That would certainly be something about which to think.