Less than a week elapsed between the time I first heard it mentioned to the actual occurrence. Sport Business Journal editor Abe Madkour theorized during the March 27 Morning Buzzcast podcast “you could almost see sports being eliminated as well” as a reaction to the news that Division I conferences would receive 63% less funding from the NCAA due to cancellation of March Madness and spring sports.

On April 2, it happened. Old Dominion University discontinued wrestling. While ODU says that it was considering this before the virus hit, it most certainly will not be the last time a sport is eliminated as a result of decreased revenues in the wake of the health crisis. And while no athletic director in the country will go on record at this stage saying he or she is considering eliminating sports, the reality is that may be the only fiscally responsible thing to do.

As recently as yesterday (April 8), The Athletic’s Nicole Auerbach said on the daily podcast, The Lead, “You are going to see a ton of sports get cut, a ton of scholarship opportunities get taken away. And it will just fundamentally reshape the way college sports looks.” Auerbach had written previously about the financial challenges facing athletic directors on April 2.

When athletic directors say there will be a football season, whether it is in the fall, the winter, or the spring, what they are really saying is “we need football so we don’t have to cut other sports.” If revenues shrink, expenses need to be reduced. Carrying 24 varsity sports, when the NCAA mandated minimum is 14, makes little fiscal sense.

Even with a football season that is close to normal, the legacy of the coronavirus and the indefinite cessation of college athletic competition may very well be a streamlined offering of college sports, with a heavy emphasis on those sports which attract large fanbases, commonly referred to as “revenue” sports. Those sports not fitting into this category are frequently known as “Olympic” sports. And while that moniker is designed to be more flattering than “non-revenue” sports, the reality is those are the sports in the most tenuous position going forward.

Since no AD will likely have this conversation publicly, let’s have it here. The conversation is very different between Division I and, say, Division III where athletes make up 50% or more of the student body on a given campus. The focus here is Division I, where athlete percentages are typically less than 4% of the student body.

What if, in a post-coronavirus world, Division I athletic administrators say, “finances are squeezed. What is it we really do? We really are in the entertainment business, and while we would like to support student-athletes in a variety of programs, it no longer makes fiscal sense to do that.”

How would that look? Could Division I administrators change bylaws and say, for example, “we want football, men’s and women’s basketball, men’s and women’s ice hockey, baseball, and softball. We want women’s volleyball and women’s soccer because we want girls to continue playing those sports at a young age. Let’s also add men’s and women’s lacrosse because those are fast growing sports and we need some balance in the spring.”

Five men’s sports (football, basketball, ice hockey, baseball, lacrosse) and six women’s sports (volleyball, soccer, basketball, ice hockey, softball, lacrosse). All team sports. All sports which have avid fan bases. All sports which charge admission and are television friendly.

To be clear, I do not believe this will happen. Clearly, this idea has many holes beyond the need for the NCAA to alter its bylaws, and is subject to deserved critiques. Will we see schools in the south like my employer, the University of Arkansas, fielding ice hockey teams? Probably not. Reasonable minds will decide what the appropriate minimum number of sports necessary to be included in the association. But before you @ me, this is just a hypothetical. The result, perhaps, of too many hours inside staring out the window hoping this whole health crisis goes away.

I am not a Title IX expert, and I am not insensitive to that important piece of legislation, but we can argue schools have been manipulating the proportionality prong of the three-prong test for years in order to demonstrate compliance. Why would we expect that to change? Instead of 49-athlete women’s rowing teams (see, for example, Ohio State’s current roster), we might have 49-athlete women’s soccer teams.

The big loser in this scenario is, of course, the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) which stands to see its athlete development pipeline for “Olympic sports” erased entirely. But is that college athletics’ problem?

Is it finally time for the NCAA and its institutions to walk away from the USOPC as it has done on occasion in the past? What does college sports receive in exchange for supporting the Olympic movement beyond the public relations benefit of saying they have Olympic fencers on campus?

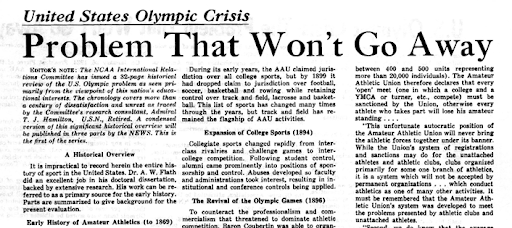

A little more than two years ago, I explored the frequently contentious relationship between the USOPC and college athletics for Athletic Director U. It is now apparent, perhaps imperative, these two organizations come together and figure out how to work together. Absent a sharply increased level of cooperation, it is conceivable “Olympic” sports at the college level may cease to exist.

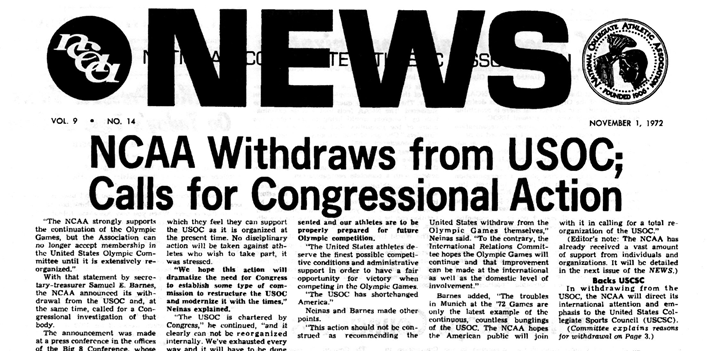

NCAA News, November 1, 1972

In that piece two years ago, I cited Lead1 President and CEO Tom McMillen, himself a former Olympian, and his February 2018 article titled “Without college sports, there would be no U.S. Olympic team.” That statement is as true today as it was then. College athletics provide valuable developmental opportunities for athletes in “Olympic” sports at little or no cost to the USOPC and its NGBs. Further, athletes who have exhausted their college eligibility still train on college campuses.

Just last month, the USOPC asked Congress unsuccessfully for a $200 million lifeline in the CARES Act to provide “financial help for 2,550 athletes, as well as sport NGBs with about 4,500 full-time employees,” according to Will Hobson in the Washington Post on March 26. Hobson correctly points out the struggling restaurant industry employs roughly 15.6 million Americans by industry estimates. Understandably, the USOPC was not high on Congress’ priority list.

To be certain, the USOPC is in complete disarray. Venerable (I hope they don’t dislike the word) Olympic sportswriters Alan Abrahamson and Phil Hersh both authored deserved takedowns of the USOPC for its $200 million ask, criticizing the methodology by which the USOPC arrived at the figure (there was no methodology) and the ridiculously high executive salaries paid by the same NGBs seeking handouts (there are notable exceptions, so please read their pieces).

Andrew Keh and Matthew Futterman wrote in the New York Times on April 4 that of the $200 million the USOPC will lose in 2020 from media rights, just $13 million, less than 7 percent, was scheduled to go directly to athletes, underscoring the importance of the Olympic-college athletic relationship.

Exactly whose responsibility it is to prepare American athletes for international competition should be clear. The Amateur Sports Act passed in 1978 spells this out. In practice, the USOPC has delegated this responsibility to NGBs who have been more than happy to allow college athletic programs to assume development responsibilities at no cost to the NGB.

The challenge for NGBs exists in that their mission also includes sport development at grassroots levels, officials education, coaching certification, and event management. Their revenues are in the form of membership fees, allocations from the USOPC, sponsorship, and, for the lucky ones, media rights.

On the eve of the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, the NCAA boasted that “NCAA student-athletes make up most of Team USA.” By NCAA figures, 417 of the 555 (75%) U.S. Olympic athletes were incoming, current, or former NCAA athletes. But even that figure represents public relations spin. Claiming swimmer Missy Franklin, an Olympic star as a high schooler during the 2012 Olympics before enrolling at the University of California, seems disingenuous at best. Franklin “competed” for two years before announcing she would turn pro since NCAA rules prohibit her from making money in sport while competing. Not all 417 former NCAA athletes in Rio de Janeiro had the same college experience.

Imagine USA Field Hockey with its annual budget of less than $10 million trying to coordinate an elite-level development system, while simultaneously growing the sport at grassroots levels, without colleges to provide year-round practice and conditioning. No wonder all 16 of its 2016 athletes had played college field hockey.

Field hockey was similar to basketball, where 100 percent of the men’s and women’s players had college experiences, even if it was only one-and-dones like Kevin Durant at Texas or Carmelo Anthony at Syracuse.

| Sport | 2016 Team USA Athletes | # of College Athletes | % College Athletes |

| Basketball | 24 | 24 | 100% |

| Diving | 10 | 10 | 100% |

| Field Hockey | 16 | 16 | 100% |

| Rowing | 41 | 41 | 100% |

| Swimming | 47 | 46 | 98% |

| Track and Field | 129 | 124 | 96% |

| Water Polo | 26 | 25 | 96% |

| Soccer | 18 | 17 | 94% |

| Volleyball | 32 | 30 | 94% |

| Golf | 7 | 6 | 86% |

| Triathlon | 6 | 5 | 83% |

| Fencing | 17 | 14 | 83% |

| Sailing | 15 | 10 | 67% |

| Wrestling | 14 | 9 | 64% |

| Synchronized Swimming | 2 | 1 | 50% |

| Shooting | 20 | 6 | 30% |

| Gymnastics | 18 | 5 | 28% |

| Tennis | 11 | 2 | 18% |

Sources:

https://www.teamusa.org/road-to-rio-2016/team-usa/athletes

https://www.ncaa.com/news/ncaa/ncaa-and-olympics/2016-07-29/2016-rio-olympics-ncaa-student-athletes-make-most-team-usa

The NCAA also takes credit for athletes in the following sports which do not have an NCAA championship: canoe/kayak, cycling, rugby, taekwondo, and weightlifting. Those athletes participated in different sports while in college. The NCAA reported zero former athletes in the following sports: archery, which may present products like that target quiver, badminton, boxing, equestrian, judo, modern pentathlon, and table tennis.

In considering the above chart, most of the high percentage sports were, dare we say, “Olympic” sports. Two sports, tennis (18%) and gymnastics (28%), were remarkable for the extremely low percentage of college athletes as Olympians. Which raises the question, why are colleges sponsoring sports such as these?

Back to the hypothetical questions… What if athletic directors decide it is no longer their responsibility to aid the U.S. Olympic team by sponsoring “Olympic” sports such as field hockey, gymnastics, wrestling, and water polo? We could certainly see more sports suffer the same fate as Old Dominion’s wrestling program, which brings me back to tennis. If ever there was a college sport which could be eliminated it is tennis.

Consider this. The U.S. Tennis Association does not need universities to help train future Olympians, the rare Olympic sport that does not need college athletics. Further, the vast majority of collegiate tennis athletes in Power 5 schools come from outside the United States. Scholarships are not going to American high school seniors. And, for those who are domestic athletes, many hail from private academies including an inordinate number from Laurel Springs Online Private School. We can save the debate around awarding athletic grants-in-aid to athletes from online private schools for a different day.

On April 6, 2020, I visited the men’s and women’s tennis web pages for all 14 SEC schools. Sixty percent (76/126) of men’s tennis players listed on the official athletic web page were from outside the United States. Fifty-three percent (61/115) of women’s SEC tennis players are from abroad. At Kentucky, all 11 men and seven women (100%) on its tennis rosters were foreign-born.

According to data from the Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act housed by the U.S. Department of Education, Kentucky spent more than $22,000 per male tennis athlete, the third-most among Wildcat men’s sports (after basketball and football). Kentucky spent nearly $25,000 per female tennis athlete, behind only basketball, volleyball, and softball.

I consulted EADA expense reports for all other universities in the SEC and found Kentucky was in the bottom third of conference schools on expense per tennis player. Mississippi State, where eight of nine men’s players are international, reported spending nearly $38,000 per men’s player. South Carolina, where four of 10 women’s athletes are international, reported spending around $35,000 per women’s player, more than they spend per athlete for its top-ranked women’s basketball program.

I am confident athletic directors are keenly aware of revenues and expenses around each of their sports. Sports where equipment costs are high (e.g. fencing and rowing) or where facility costs are high (e.g. swimming and diving) or where there is limited competitive future beyond college (e.g. tennis and gymnastics) should be concerned.

Pointing this out won’t make me popular among the tennis community, or the gymnastics community, or the wrestling community (a sport in which I worked for several years in the 1990s). For that I am sorry. I like those sports, and I have been privileged to know many student-athletes and coaches in those sports.

And as much as we all like college sports, most of us also really enjoy the Olympic Games. If anything, I am hopeful the stress of the current financial situation will finally force the USOPC and the NCAA to find common ground and work collaboratively to the benefit of college athletes. Otherwise, the alternative, it seems, may be for NCAA institutions to get out of the Olympic sport business altogether.