The COVID-19 pandemic is having a devastating financial impact on college athletics. It has created unfortunate layoffs, furloughs, and sport cuts that are impacting many people. And challenges are still ahead as the full effects of a dramatically altered football season are realized. In these extraordinary circumstances, leaders at every school are working earnestly to make the best possible decisions about athletics department finances and overall institutional budgets.

At the Power Five level in particular, athletics departments are experiencing annual revenue shortages upwards of $50M – budget gaps too large to be solved by belt tightening alone. Athletics programs are thus in the process of sorting out financing that will create a way forward.

But as schools confront daunting short-term deficits and additional long-term debt obligations, many will also consider eliminating sports to reduce operating costs. Several schools – including Stanford, Iowa, and Minnesota from the Power Five – have already taken action.

COVID-19 has created an unprecedented situation in college athletics, so it is tempting to attribute sport cuts, layoffs, and other financial disruptions solely to its impact. However, closer examination shows that many athletics departments were financially stressed even before effects from the pandemic. Pre-existing structural problems in the broader economic system of college sports created financial challenges for many schools that are now being dramatically amplified by COVID-19.

In particular, our economic system has encouraged FBS athletics department spending to rise in unsustainable and imbalanced ways, creating the financial overextensions that put the industry especially at-risk of the unfortunate cuts and other damage we are now experiencing.

Different Types Of Sport Cuts

Athletics departments cut sports mostly for financial reasons. But looking more closely at particular circumstances, there are nuanced differences in the ways that financial challenges lead to sports being dropped.

In some cases, there simply isn’t enough money for an athletics department to maintain its existing portfolio of teams. It is already operating with maximum efficiency when unexpected adversity pushes its finances into an untenable situation. The athletics department just can’t continue operating all of its existing teams, even at the most basic level1. Sport cuts due to this kind of absolute funding shortage occur mostly in DIII, DII, FCS, and in some Group of Five situations.

In other instances, sports are cut because schools decide there isn’t enough money on a relative basis to sustain their current portfolio of teams. This is the rationale behind most sport cuts at the FBS level.

In these cases the athletics department could rearrange its budgets to retain all of its teams, but doing so would require a level of frugality deemed unacceptable relative to the resources being invested by its competitors. In other words, Iowa, Stanford, and Minnesota could internally rearrange $120M+ budgets and fund their teams more modestly as revenue recovers, but they would unreasonably be choosing to competitively disadvantage themselves by doing so.

The decision to cut teams in these instances is thus heavily influenced by characteristics of the external environment – such as the amount of money being invested by other schools and the level of resources necessary to maintain an acceptable level of competitiveness. Consequently, dropping sports occurs not only because of local circumstances, but is also driven by problematic effects caused by the broader economic system of college athletics.

Increasing Income Gaps Between Competitors

Two economic system issues in particular affect whether schools can sustain all of their teams. The first is income inequality.

There has long been resource imbalance in college sports, but this trend has accelerated in recent years. Cumulative annual revenue in FBS increased by over $3.5B between 2010 and 20182, but this new income disproportionately flowed to already-wealthy schools. Median revenue in the top quartile of FBS grew during this period by 57% (i.e., a large compounding effect on budgets that were already the biggest) compared to a median change of 37% in the third quartile3.

Income inequality is expected to grow further during the next round of conference media deals, especially within the Power Five. Recent analysis by Navigate Research forecasts the annual difference in revenue between schools in the Pac-12 and Big Ten will increase to almost $30M on average by 20294.

From a school-by-school perspective, it is logical for the most popular programs to capture the largest share of revenue. But viewed collectively, a widening resource gap between a handful of the highest-income schools and everyone else adds more financial stress to our system. Even when prosperous times return, less-wealthy schools at each competitive level will find it more difficult to handle financial setbacks without falling unmanageably far behind. Rising income inequality increases the chances that less-wealthy schools will be forced to consolidate resources behind fewer teams in order to remain competitive.

Lack Of Meaningful Savings

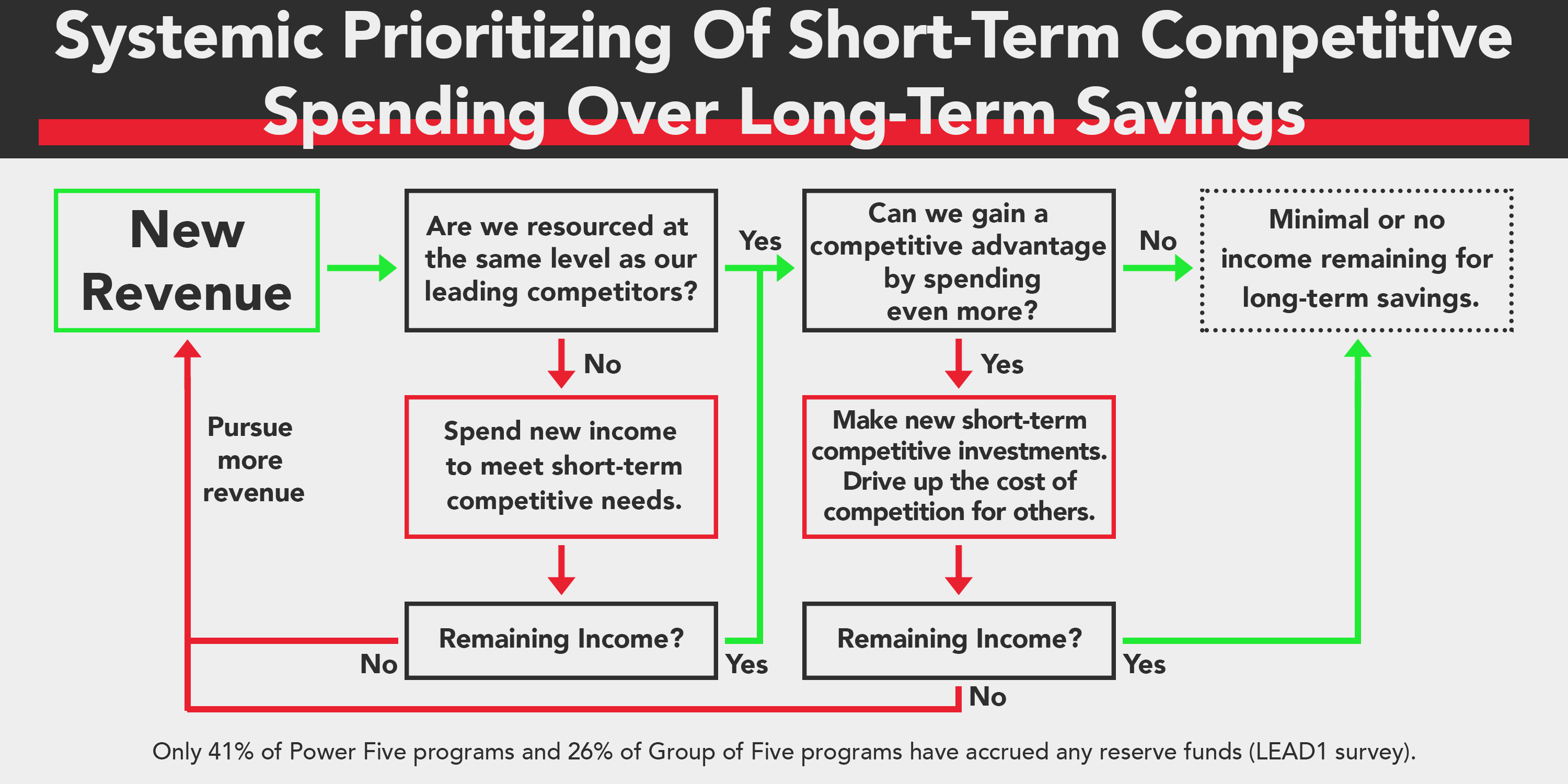

A second problem is that the economic system in college sports is structured to encourage spending and discourage saving. Consequently, few schools have built meaningful reserves that can be used to backstop revenue shortfalls in difficult times.

The non-profit structure of athletics departments encourages increased spending. As is the case with most non-profits, athletics departments spend basically all of the revenue they earn each year on their mission-focused work. Unlike in private business or professional sports, there are no owners with an incentive to retain excess income for profits or future needs.

Accordingly, spending in college athletics always rises in direct proportion to revenue5, and the benchmark for competitive investments is always established by the highest revenue earners. Other schools try to keep pace as best they can, which makes them reluctant to divert income away from current spending in order to build long-term savings.

This tendency to prioritize spending over saving is reinforced by the fierce zero-sum nature of competition in college athletics. Unlike in other non-profit industries, an athletics program can only accomplish its competitive mission (win) if another fails (lose), and there are significant rewards for winning and significant penalties for losing. Accordingly, there is always urgency to fund the next short-term competitive need, and schools are often willing to forgo long-term savings in order to do so.

Systemic prioritization of spending over saving has resulted in only 41% of Power Five programs and 26% of Group of Five programs being able to accrue any kind of reserve fund6 – even despite annual FBS revenue increasing by over 150% since 20057.

The lack of widespread savings following a period of robust prosperity seems surprising at face value, but actually serves to illuminate the deficiencies in our economic system. Athletics departments are less resilient to financial setbacks specifically because of how our economic system works.

Limit Spending For Long-Term Sustainability

We must make changes to our economic system to ensure broad-based college athletics can survive over the long-term. The most important change we can make is to create rules to limit athletics department spending. Limits on spending help for three reasons.

First, they break the direct link between revenue and expenses that problematically drives up costs in non-profit college sports. Slowing down cost growth eases the financial pressure on schools that aren’t at the very top of the revenue generating pyramid.

Second, a limit on spending effectively caps the maximum resources available to any team, thereby limiting the size of possible resource differences between teams. Athletics departments experiencing a financial setback can support teams at slightly reduced levels of investment – i.e., rather than eliminating them – without subjecting themselves to an unreasonable competitive disadvantage.

And third, spending limits create a point above which money cannot be spent on yet another urgent short-term priority. Excess income can thus be saved for emergency use and more athletics departments will be able to build up meaningful reserve funds.

Spending limits should apply on a sport-by-sport basis, be tailored appropriately for each competitive level, and structured to ensure gender equity. An intelligently designed system can also account for cost-of-living differences, tuition-driven scholarship cost differences, and various other idiosyncrasies8. Spending limits also create a number of other positive impacts for student-athletes and ticket-buying fans that are beyond the scope of this article but can be read about in detail here.

Leadership For Positive Change

Creating effective policy to limit spending is feasible. Garnering the political support to actually implement it is the hard part. Especially if salaries are impacted, limits on spending can be perceived as conflicting with American ideals of free markets and capitalism9. Congressional involvement is likely required to navigate antitrust complexities.

Additionally, it is difficult in college athletics to generate public advocacy for ideas that haven’t yet reached a tipping point of widespread support. As is the case in politics, job security in nonprofit college sports depends in large part on popularity (as opposed to shareholder returns in the private sector), so some administrators might be hesitant to visibly support a policy that a portion of constituents could find controversial. Even when many people privately support such a policy, the leadership culture in college athletics simply does not encourage them to speak out about it.

But we’ve arrived at a moment in our industry where people are more willing to consider ideas that might previously have been viewed as unfeasible. The gravity of our current circumstances has sparked an urgency to solve problems and increased our openness to different kinds of solutions. There is a growing collective awareness that change is necessary for the long-term viability of broad-based college athletics. Hopefully, we find the courage and leadership instincts required to rebuild our economic system in a stronger, more sustainable, and more equitable fashion after COVID-19.

- Occasionally a school will cut a team because a change in circumstances means the athletics department must increase spending from its current levels but it can’t afford to. For example, if a school experiences a substantial increase in undergraduate students of one gender, it must grow participation opportunities for that gender to remain in proportionality compliance with Title IX. But if the school is unable to absorb the required increase in spending, the only remaining choice is to cut opportunities for the opposite gender (i.e., even if it could sustain its current portfolio of teams).

- Per Knight Commission’s CAFI database, includes public schools only.

- Per Knight Commission’s CAFI database, includes public schools only.

- Regional differences in fan avidity for college sports drive differences in revenue potential. For example, see this Google Trends page for the relative frequency of searches about college football in various parts of the United States on a per capita basis.

- This effect in higher education more generally is called the “revenue theory of cost”. Indeed, cumulative annual FBS spending grew by $3.6B during 2010-2018, consuming all of the revenue gains during that period. Per Knight Commission’s CAFI, includes public schools only.

- LEAD1 “State of Athletics” presentation (link).

- Per Knight Commission’s CAFI database, includes public schools only.

- For the sake of example, the base spending limit could be set at the 75th percentile of EADA reported FBS expenditures from FY2018. At this level, FBS football teams could not exceed $31,714,090 in total expenses. Men’s (and women’s) basketball teams could not exceed $9,604,624, baseball (and softball) teams could not exceed $3,308,388, and women’s (and men’s) soccer teams could not exceed $1,955,527. Marginal upward or downward adjustments would be made based on local differences in scholarship costs, consumer price index, and other idiosyncrasies where adjustment is justified by publicly available data. These EADA figures include scholarship costs, which would not necessarily be counted as part of the limited expenditures because of tuition-driven differences in scholarship spending. Further analysis could assess whether limits should include or exclude facility expenses, or adjust for conference travel differences, etc.

- These ideological objections are based on a mistaken assumption that college athletics functions like a free market in the first place. Unpacking this point in detail is a worthwhile exercise, but beyond the scope of this article.