For Dave DeCew, athletic director at New England College in Henniker, N.H., the addition of men’s golf to his department’s offerings had been in the works for a while. So while the current pandemic did not serve as the catalyst for the change, the pandemic did not serve as a deterrent either. “It was something we were planning already. We felt like we had a coach on campus in mind, and it was as good of a potential option as we could find,” DeCew told me.

And so, on March 20, 2020, eight days after the NCAA canceled winter and spring competitions, New England College became the first university to add a sport in the pandemic.

“We had great buy-in from our president and administration. They recognize sports as a vehicle to drive enrollment,” said DeCew, who acknowledged men’s golf had the added benefit of not needing access to existing on-campus athletic facilities which were already saturated.

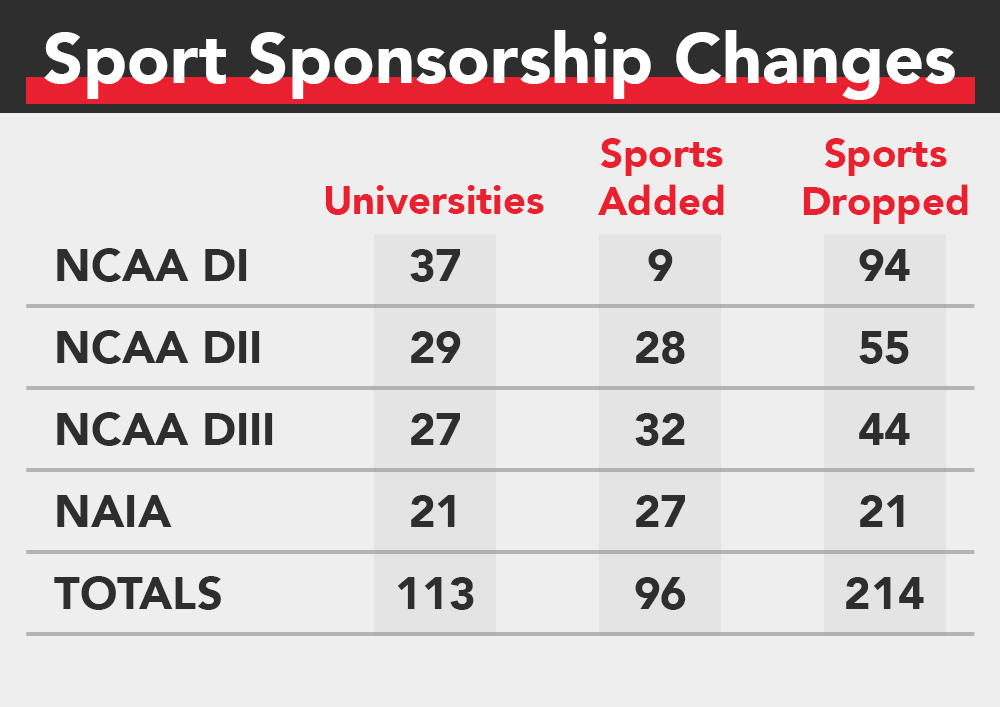

Men’s golf at New England College is one of 32 sports added at NCAA Division III institutions since mid-March, and one of 96 added (as of October 24, 2020) across the entire landscape of college athletics at four-year institutions based on data accumulated and kept by Athletic Director U. And while much of the media attention has focused on the high profile programs cut at Power 5 schools such as Minnesota, Iowa, and Stanford, the reality is the overall net number of sports eliminated since the pandemic, when excluding sports at universities which have ceased operations altogether, is just 46.

As the table below shows, however, that storyline differs dramatically across divisions of college athletics. As of October 24, 2020, NCAA Division I has lost a net of 85 sports, while NCAA Division II is down 27 programs while Division III is only down 8 programs, again controlling for school closures. Meanwhile, the NAIA has witnessed a net increase of 6 sports. Of the 214 sports dropped, 75 are the result of schools closing entirely or ceasing all athletics.

NOTES:

- DI does not include 11 sports reinstated at Brown, Bowling Green, Alabama-Huntsville and William & Mary as either added and dropped.

- DII includes 11 sports dropped by Notre Dame de Namur University ceasing athletics and 17 sports from Urbana University closing.

- DIII includes 13 sports dropped by JWU Denver ceasing athletics and 14 sports from MacMurray College closing.

- NAIA includes 11 sports dropped by JWU North Miami ceasing athletics and 9 sports from Holy Family College closing.

How these figures compare to a normal year is not known. In other words, are the 96 programs added during the seven-month window since March consistent with non-pandemic years? I am not sure. Certainly the elimination of 214 total sports in seven months related to the financial challenges associated with the pandemic is newsworthy, generating increased buzz recently. USA Today columnist Christine Brennan called into question university logic behind cutting non-revenue sports, stating that by “eliminating these sports and driving away these student-athletes, they are weakening their university community.”

Former athletic director Donna Lopiano, writing on Forbes, also questioned the thought process behind cutting sports, although for different reasons, suggesting universities “used Covid as the convenient excuse and smokescreen to justify the sacrifice of non-revenue sports that they have wanted to drop for years so they could redirect those budget dollars back to football and basketball.”

Finally, Tom Farrey of the Aspen Institute wrote in an editorial published in the New York Times, cutting varsity sports might not be so bad because many of them will transition to club sports. “How terrible could that shift be? Club athletes represent their colleges, wear the colors, but play more on their terms, not those of an athletic department groaning under the strain of an N.C.A.A. rule book and of a business model that turns many athletes into employees without paychecks.”

While it is easy to pontificate about sports being cut – heck, I did that several months ago for Athletic Director U. – few people are writing about adding sports. On the surface, adding sports seems like a potential solution for many of the tuition-dependent Division II and III schools staring down a crisis if declining enrollment and shrinking revenues. Even the NCAA’s own chief medical officer sounded the alarm during this month’s Project Play Summit when he suggested 20-30% of Division III schools were not likely to survive the pandemic.

So why should universities be looking to add sports? What benefits could it present to a university and its athletic department? What do the trends tell us about how athletic administrators view the sports to be added?

The answer to the first two questions was explored in a July story by Eben Novy-Williams for Sportico who had sports economist Andy Schwarz analyze the financial cases of Central Michigan, Akron, and Western Kentucky. While WKU has not cut any sports, CMU and Akron both have, and all three have witnessed steep enrollment declines. “In all three cases, (Schwarz) found that the schools would make more money if they nearly doubled the number of equivalency sports they offered.”

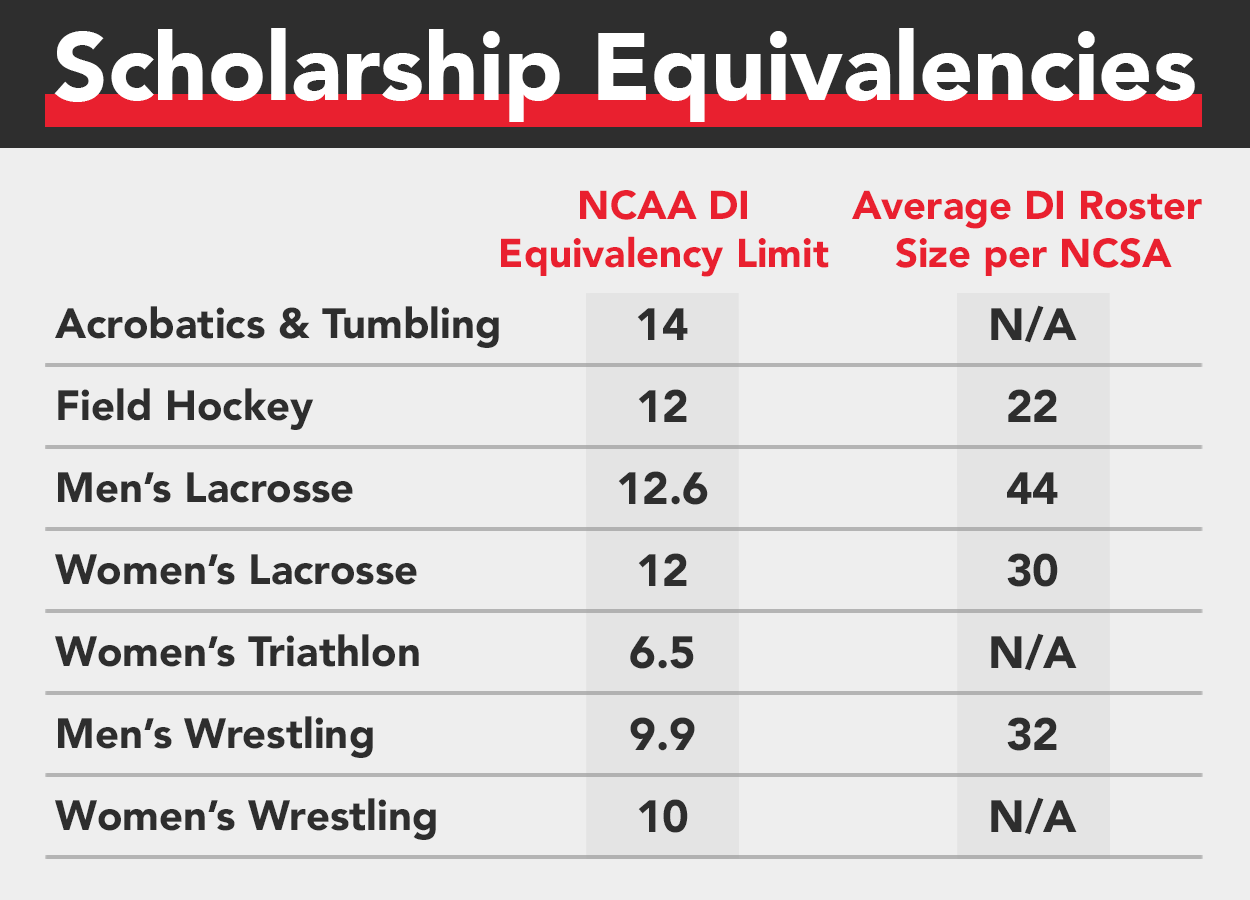

In particular, sports which might fit this description such as field hockey, lacrosse, and wrestling, are those with low NCAA DI equivalency limits but no limits on counters. I also included women’s triathlon in the chart as that is an emerging sport which has seen growth at the DI level since the pandemic. To get a sense for average roster size, I consulted Next College Student Athlete’s (NCSA) recruiting guides for each sport.

Each of these sports exhibits a participant-to-equivalency ratio of anywhere between 2:1 to almost 4:1 (assuming they are fully funded). As Schwarz told Novy-Williams, “I would imagine that for a lot of schools that are really struggling with enrollment, if they could find a way to double the size of the so-called non-revenue portion of the athletic department, they would make more money.”

In fact, the higher the ratio of participants to equivalencies allowed, the more athletes have to cover their tuition through other means, and the more (potentially) profitable these sports can be for the university as a whole. So, are the sports mentioned above being added during the pandemic. The quick answer is, no.

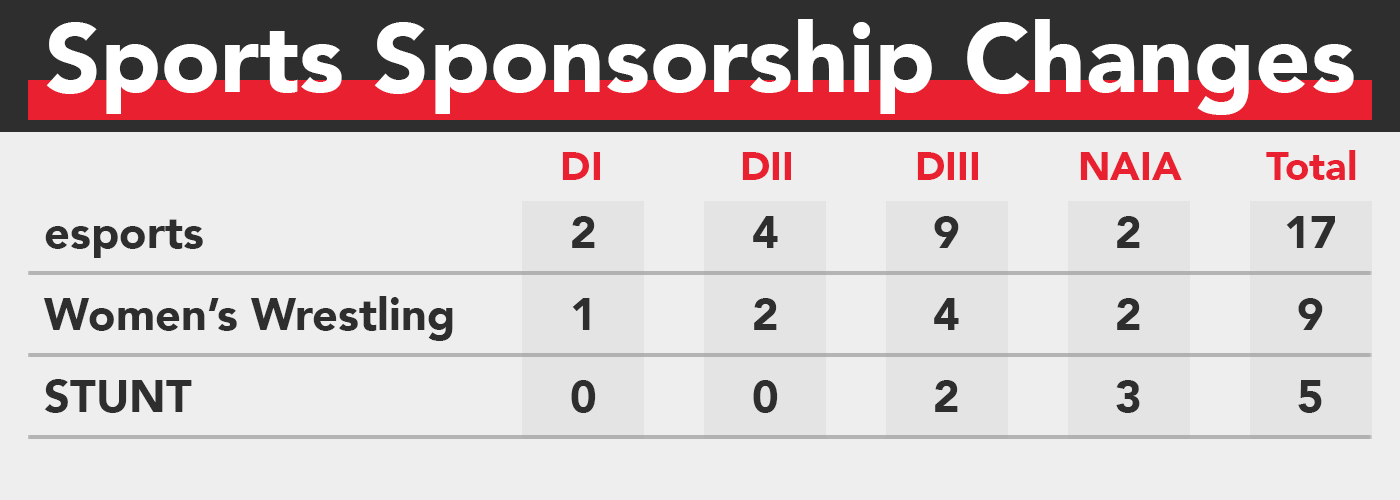

The variety of sports added during the pandemic is significant when viewing men’s and women’s programs as separate, but only three sports saw gains of five or more programs. Overall, sports recognized by the NCAA as Emerging Sports for Women have seen increases with new programs added in women’s wrestling, women’s triathlon, women’s acrobatics and tumbling, and women’s rugby. In addition, STUNT recently received a recommendation from the Committee on Women’s Athletics to join the program. Overall, 19 of the 98 sports added during the period fall in this group, and that is a good thing.

But it is the most-added sport which raises eyebrows. To many, the growth of esports is not surprising. The NCAA featured it on the cover of Champion magazine in March 2018, prompting me to write about its growth in July 2018. Earlier this month, Team Marketing Report asked the question of whether esports could fill a void on mid-major campuses. With 17 new varsity programs since March, most at tuition-dependent universities, it certainly seems that is the case. As TMR reported, “the interest in esports as a viable property that can attract global—and co-ed—teams of students from various disciplines is intriguing to many.”

And, as if esports needed more validation, Learfield IMG College is aggressively entering the esports event and rights space. But before athletic departments rush to add esports programs, administrators need to understand the ecosystem of esports is different than that of traditional sports, and vice versa. Perhaps as a result, we are seeing growth on the academic side of universities to create degree programs which offer students the ability to learn more about the emerging field.

One such program at the Division I level is a new graduate certificate program in esports management from East Tennessee State. Faculty member Dr. Natalie Smith, the program coordinator, characterized the program’s goal as bridging the knowledge gap between esports and traditional sport management. “We have heard from esports practitioners there is a dearth of people who have esports knowledge and management knowledge.” Smith specifically cited areas such as brand alignment, development of public relations and marketing plans, and creation of a labor pool as areas of challenge for esports.

Further, she told me, when in concert with one another, esports varsity and academic programs have the ability to navigate the changing demographics of today’s college students. “We know there will be a dropoff in enrollment of college students and we know there is a dropoff in fanship of traditional sports from today’s high school students.”

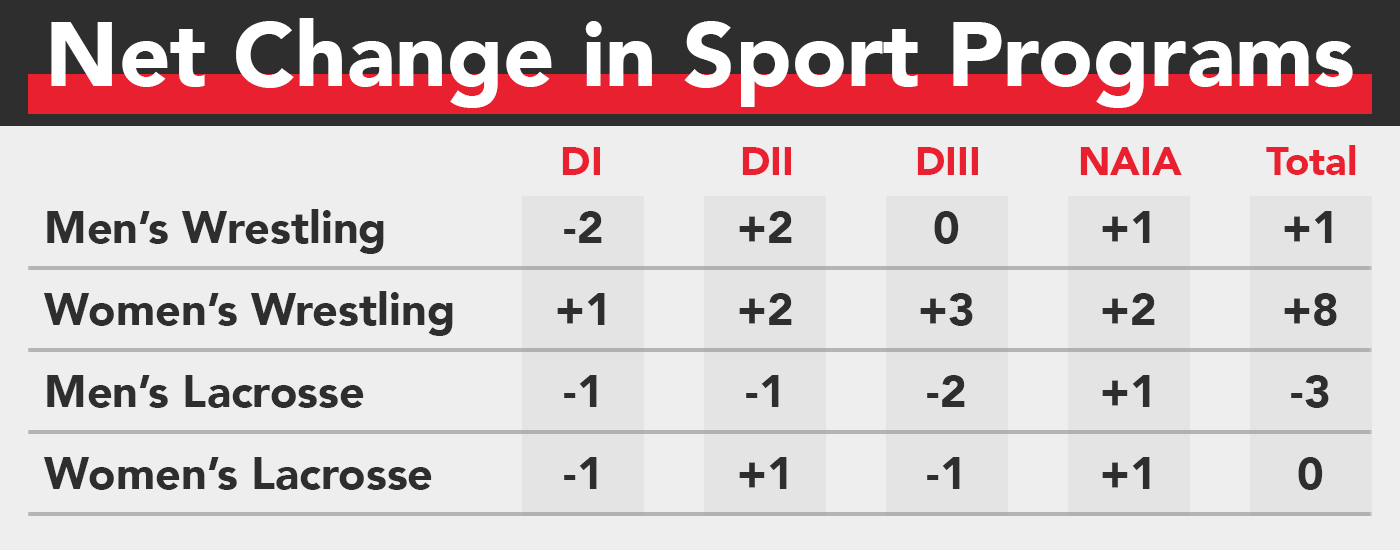

Will universities continue to add esports? Probably. We all know how athletic departments tend toward isomorphism, so copying one another seems likely. Plus, the NCAA does not currently place limits on esports grants-in-aid. But, should universities be adding something different instead? Again, the answer is probably. And those sports, based on participant-to-equivalency ratios, suggest wrestling and lacrosse should be at the top of the list.

The National Federation of State High School Associations is unable to publish its annual participation data for 2019-20 due to the loss of spring sports. So, using 2018-19 figures we find that participation in girls’ wrestling is up 344 percent (!) during a 10-year span from 2009-10 to 2018-19. The number of participants grew from 6,134 to 21,124 while the number of programs grew from 1,009 to 2,890. So, it is not necessarily surprising that since March, universities have added nine women’s wrestling programs.

Similarly, youth lacrosse participation is exploding as evidenced by increases of nearly 1,000 programs each on the boys and girls side at the high school level in the past decade. The number of participants is up greater than 30,000 girls and 23,000 boys. However, as the table shows, lacrosse programs have not only not grown, but they suffered a net decrease of three programs since March.

Even before most schools had announced pandemic-related cuts, Terry Foy, CEO of Inside Lacrosse, was campaigning for schools to ADD lacrosse. “Men’s lacrosse has the capacity to drive more tuition dollars than any other men’s niche/Olympic/non-revenue sport,” Foy wrote in early May. Lacrosse sports a nearly 4:1 participant-to-equivalency ratio on the men’s side, and a 2.5:1 ratio on the women’s side.

I asked him to expand on why adding lacrosse programs makes financial sense for universities, and he immediately pointed to the participant-to-equivalency ratio. “It’s not publicly available how many scholarships a private university’s men’s lacrosse team offers, but based on my significant anecdotal research, I suspect that of the 64 programs that can offer scholarships (74 programs minus 3 service academies and 7 Ivies), the average is about 9 scholarships,” he told me. “Probably 30-35 fully funded, 20 between 8 and fully funded and about 10-15 between 0 and 4.”

Foy estimated for most D1 programs, fielding a men’s lacrosse team would produce the equivalent of 38 full tuition-paying athletes. Yet, despite the seemingly obvious financial benefits to a university, the challenge associated with going all-in on a lacrosse program is too great for many athletic administrators. “In private conversations, many administrators from departments that don’t currently sponsor men’s lacrosse say something like, ‘If we were starting from scratch, of course we’d have lacrosse.’” Foy wrote in May. “Those same administrators, though, mention that their athletic departments are already too large to add another program, and that the pain of dropping sports exceeds (or has exceeded) the economic value back to the department of subsequently adding men’s lacrosse.”