College athletic departments are preparing for U.S. District Judge Claudia Wilken to potentially provide final approval of the settlement in the House v. NCAA, Hubbard v. NCAA and Carter v. NCAA cases, which would allow for direct revenue sharing with athletes later this year. While many administrators have publicly expressed their school’s intent to participate, most have been understandably shy on specifics. After all, the settlement has yet to be approved and athletic departments are preparing to adjust to new roster limits and how the new category of expenses will fit into their reimagined budgets.

Using a combination of public comments and publicly available data, as well as insights from the collectives powered by the agency Student Athlete NIL (SANIL), here are potential revenue-sharing models, based on different athletic department profiles.

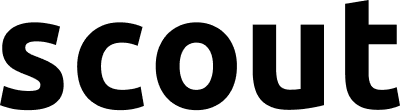

Texas Tech plans to commit ‘about 74%’ to football players

In a rare example of an athletic department publicly sharing its revenue sharing plans, Texas Tech AD Kirby Hocutt and Deputy AD Jonathan Botros shared the school’s plans with the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal in December. The school projects to share the maximum of roughly $20.5 million with “about 74% to football players, 17-18% to men’s basketball, 2% to women’s basketball, 1.9% to baseball and smaller percentages to other sports,” according to the Avalanche-Journal.

Texas Tech’s other athletic programs would share the remaining 4.1% to 5.1% of the pie, which is somewhere between $840,000 to $1.05 million.

The distribution percentages of Texas Tech’s projected annual revenue share by sport are similar to the share of annual revenue attributed to each program. ADU analyzed the three most recent financial reports that the athletic department submitted to the NCAA. Note that over this span, Texas Tech had an additional $20 million to $32 million in annual revenue classified as “not related to specific teams,” which wasn’t included in calculating the revenue percentages attributed to each sport.

Hocutt said the school won’t increase its number of athletic scholarships because that would limit the amount of direct revenue sharing payments. The first $2.5 million in additional spending on athletic scholarships will count towards a school’s revenue sharing allotment.

Texas Tech is also eliminating its education-related Alston awards in order to instead use those funds for revenue sharing, according to the Avalanche-Journal. These are examples of how there will be nuance to how athletic departments choose to structure their revenue sharing if Wilken approves the settlement.

Texas Tech’s revenue-sharing plans are directionally similar to how one Power 5 school and its partner agency have distributed money to athletes for the last year and a half.

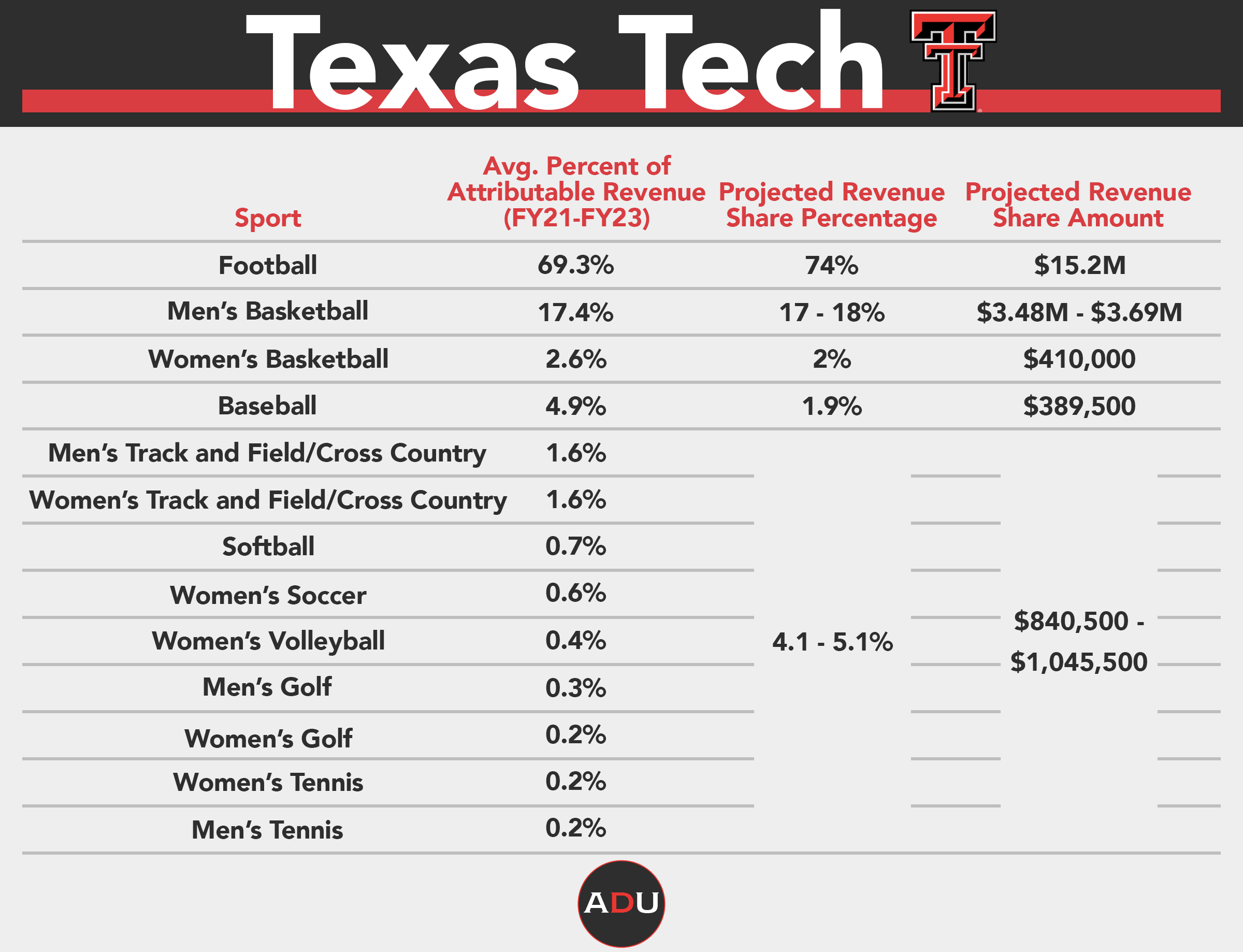

Every True Tiger Brands, LLC, has invoiced Mizzou Athletics for roughly $16.4 million from September 2023 through December 2024. The monthly invoices show the number of recipients and amount owed by sport.

Here’s a comparison between Missouri’s spending and Texas Tech’s revenue sharing plans for the four sports with the highest spending percentages.

Missouri’s payments to Every True Tiger have similarly followed the percent of attributable revenue by sport – at least for the two highest revenue-producing programs.

Missouri has attributed 72.2% of its attributable revenue to its football program, which has received 65.4% of the school’s payments to Every True Tiger. The men’s basketball program is credited with generating 23.2% of the department’s revenue and it has received 23.3% of the payments.

How will ‘basketball schools’ share revenue?

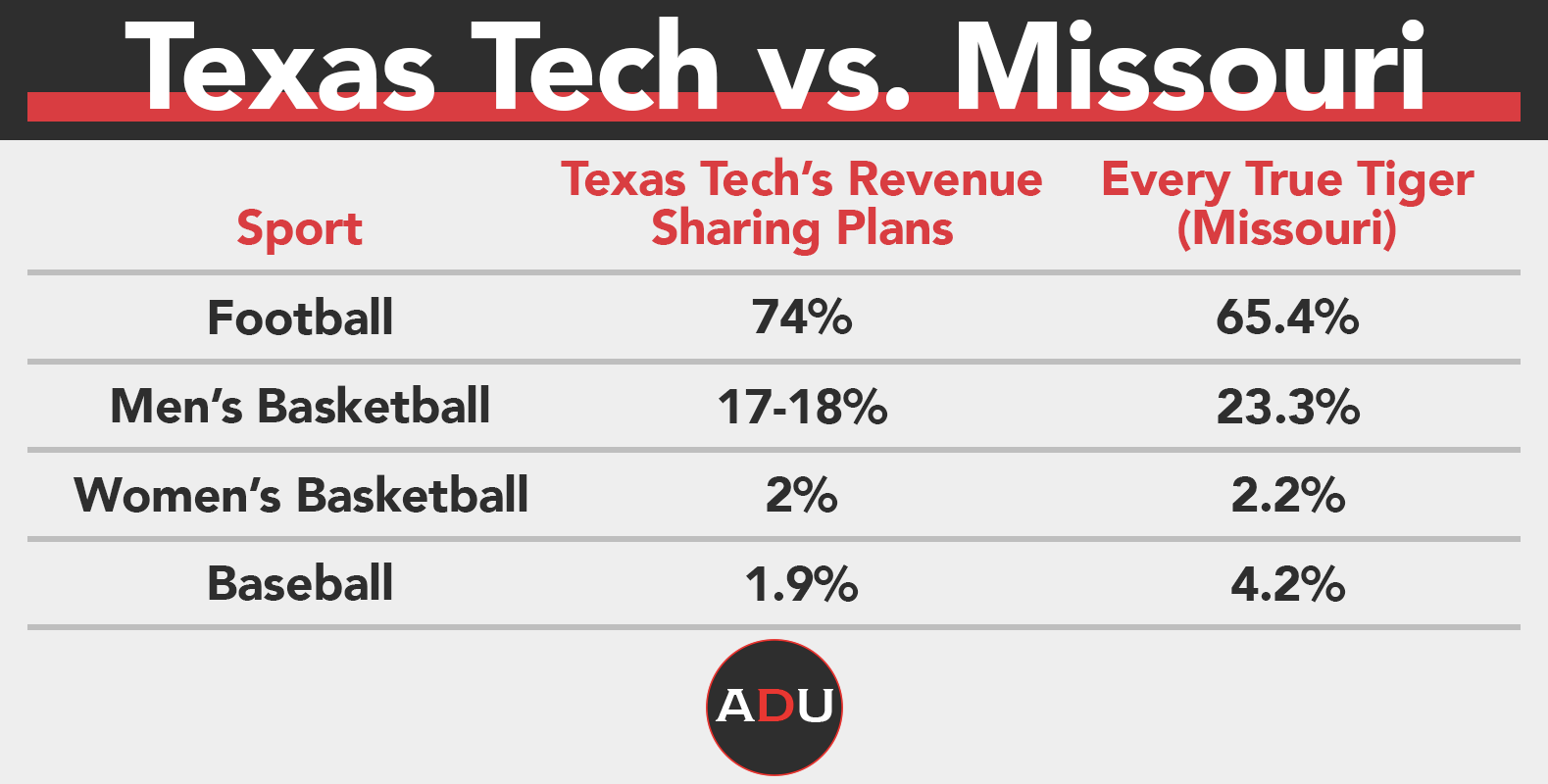

UConn, the two-time reigning men’s basketball national champion, has been among the most aggressive spenders nationally as far as the program’s operating budget, both in its total spending and the percentage of the department’s budget it represents.

While the Huskies’ independent football program has played in a bowl game in two of the last three seasons, the athletic department is known for its men’s and women’s basketball programs.

In the 2022 fiscal year – UConn coach Dan Hurley’s fourth season at the school and the season before his program won back-to-back national titles – the athletic department’s financial report attributed 62% of its revenue to the men’s basketball program.

The men’s basketball program’s average from the 2021 to 2023 fiscal years was 50.3%, followed by football, women’s basketball, men’s hockey and baseball.

Even if UConn only shares $10 million with its athletes of its roughly $100 million annual revenue (or roughly half of the proposed $20.5 million cap), and if UConn’s revenue sharing distribution follows its athletic programs’ recent revenue attribution, the Huskies’ men’s basketball players would hypothetically receive roughly $5 million and women’s basketball players would receive $1.1 million.

Depending on UConn’s long-term goals for its football program, it could provide top-level funding to its elite basketball programs while staying millions of dollars below the cap and within its roughly nine-figure budget.

Some of UConn’s Big East brethren, such as Marquette, St. John’s and Xavier, don’t sponsor football. While these departments have smaller operating budgets than some of their Division I peers as a result, they could also prioritize spending $3 million to $5 million annually on their men’s basketball team without having the eight-figure anchor of revenue-share payments for football players.

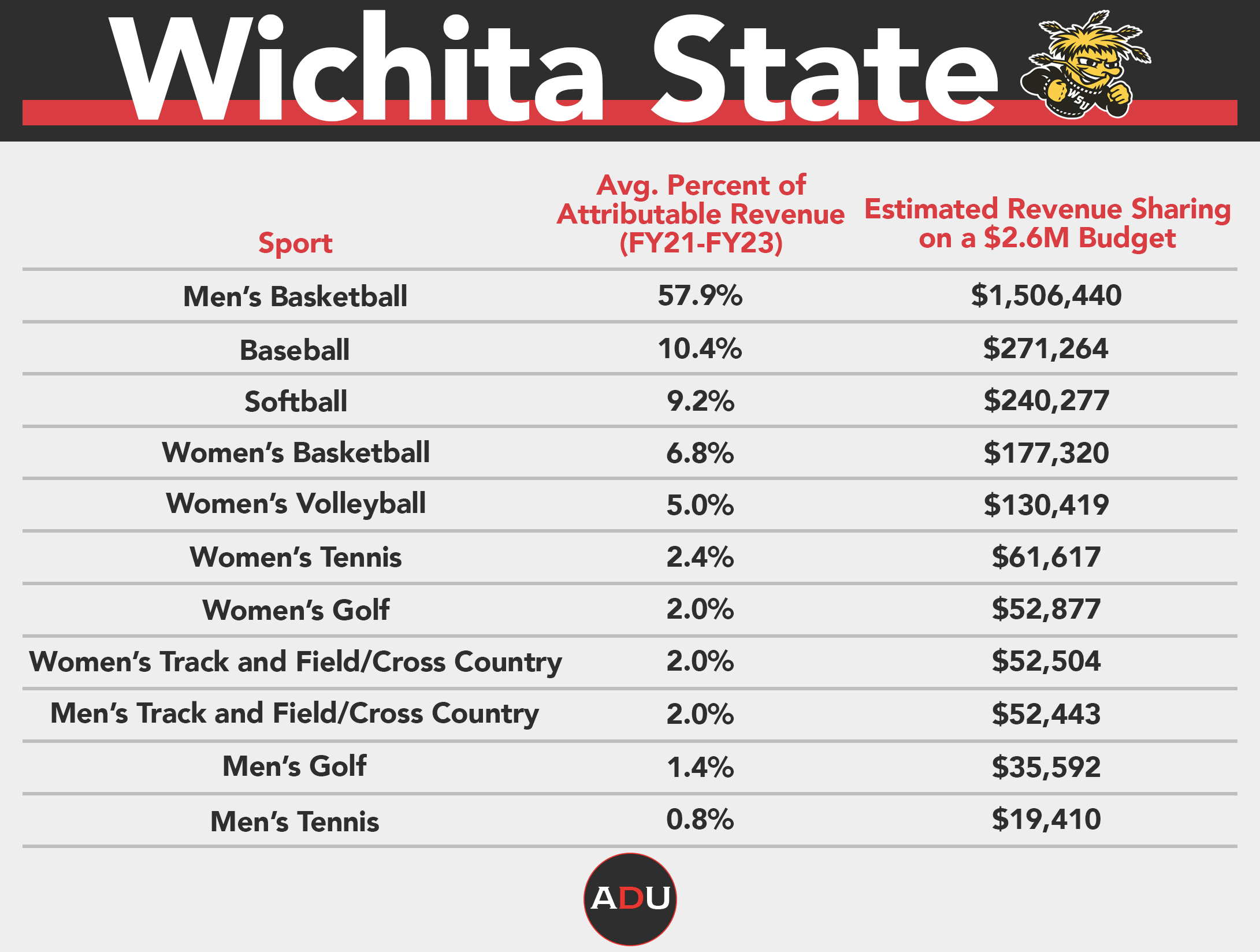

In an open letter to fans last November, Wichita State AD Kevin Saal said the athletic department estimates it will share with athletes a minimum of $2.6 million annually, in addition to $2.5 million in additional scholarship expenses.

If Wichita State only distributes its stated minimum of $2.6 million in direct revenue sharing – and if Wichita State used a similar revenue share model as Texas Tech that followed the percent attributable revenue by program – the Shockers would provide an estimated $1.5 million to their men’s basketball players.

Despite Wichita State having a quarter of Texas Tech’s total operating budget – $34.6 million vs. $136 million in FY23 – at a minimum, the Shockers could potentially afford to pay their basketball team 40 to 45% of what the Red Raiders will, based on the portfolio of sports each school sponsors.

How else could athletic departments determine revenue-share percentages?

While Wilken hasn’t approved the House settlement yet, early indications from Missouri’s recent payments and Texas Tech’s announced plans suggest that athletic departments will generally pay athletes relative to the share of revenue their athletic program produces.

But what other strategies could administrators employ?

They could choose to divvy funds by sport based on raw totals based on what amount of money it’s believed or known to take to stay competitive. If an athletic department needs to pay $12 million to football players, $3 million to men’s basketball players or $1 million to women’s basketball players, it could start with the end number in mind.

“As you can see by the numbers across various athletic departments, distributing revenue is not a one size fits all approach,” says Michael Haddix, founder of Scout, a fintech platform providing student athlete financial execution and athletic department revenue share services. “Every institution is going to have to consider a myriad of factors specific to their circumstances before deciding what works best for them to achieve their goals. Working with partners who can help them develop, analyze and deploy various revenue sharing strategies is what they should be focused on in the near term,” he adds.

Last summer, Ohio State AD Ross Bjork told several media outlets that the Buckeyes’ football players earned roughly $20 million in collective payments and brand deals over the previous year.

It’s also worth considering the post-House collective landscape at a given school. Some collectives have transitioned to act as a true marketing agency or folded entirely. For schools with collectives that will still exist in the revenue-share era, the appetite of the local collective or its donors could give an athletic department more leeway to increase its revenue sharing with athletes who compete in sports like baseball, softball or women’s volleyball if there will still be outside funding for football and basketball players.