College athletics is at a crossroads. With the passage of California’s SB206 Fair Pay To Play Act, the laws in the state now permit student-athletes to profit from their Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) – in direct conflict with existing NCAA eligibility rules. And while the bill does not go into effect until 2023, legislators across the country are now pushing for similar laws to be enacted in their state, some as soon as next year. Never before has the intercollegiate athletics model faced a more pressing inflection point that threatens to unravel the very foundation on which the amateur sport model is built upon in this country.

In an effort to continue to provide intercollegiate athletics leaders with key industry insights, AthleticDirectorU and AthleteViewpoint gathered information on the topic of Name, Image and Likeness and student-athlete compensation by surveying current Division I athletics directors on the issue. By gathering and aggregating data on the temperament of those directly responsible for addressing the changing rules around pay-to-play for student athletes, ADU hopes to provide clarity on the most important areas of focus for the NCAA and administrators in the coming months and years.

The survey was distributed to 344 NCAA Division I Directors of Athletics. 97 individuals responded, providing a 28.2% response rate. The responses were representative of the population of AD’s across Power 5, Group of 5 and FCS/Non-Football institutions with all three classifications seeing nearly identical response rates. With a 90% confidence interval, the data has a +/- 6.3% margin of error – indicating the views of the AD’s who responded are generally representative of the perspectives of all Division I AD’s.

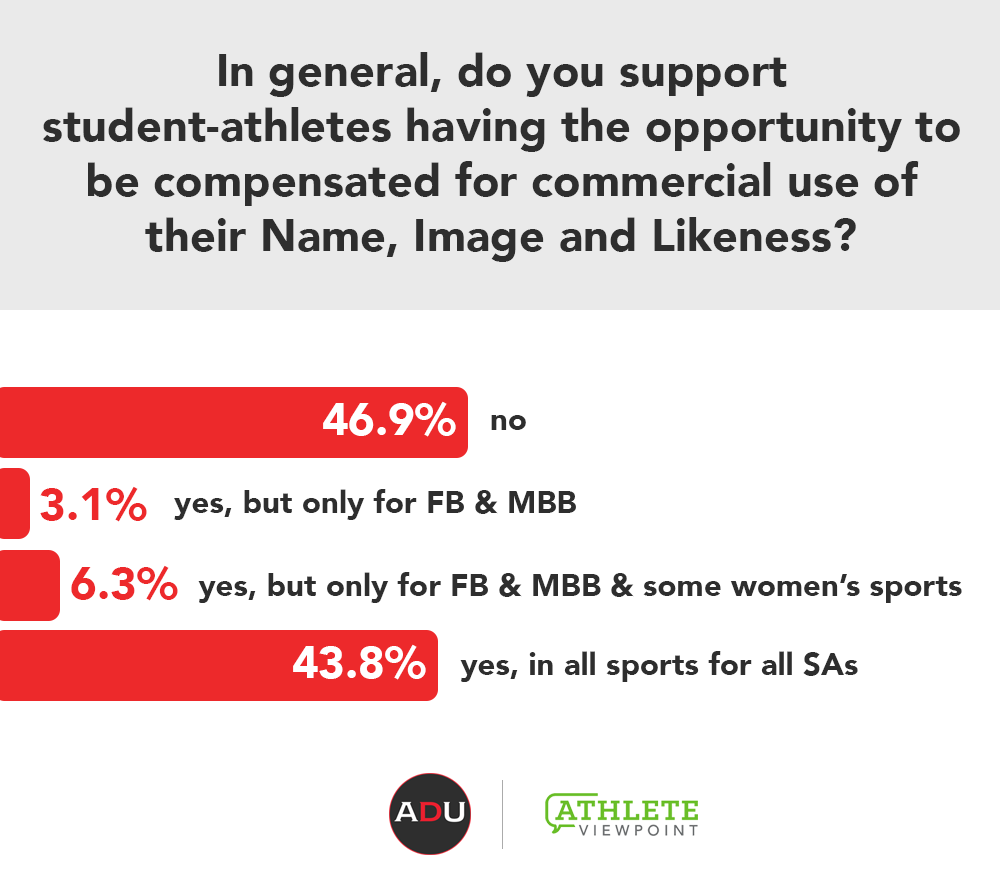

The first, and perhaps most important question, shows a split among ADs. 53% are in support of some sort of student-athlete compensation when it comes to Name, Image, and Likeness. A breakdown of the numbers reveals that ~ 57% of Power 5 ADs support NIL in some capacity while that number is as high as ~ 66.7% among Group of 5 ADs and as low as ~42.6% among FCS ADs.

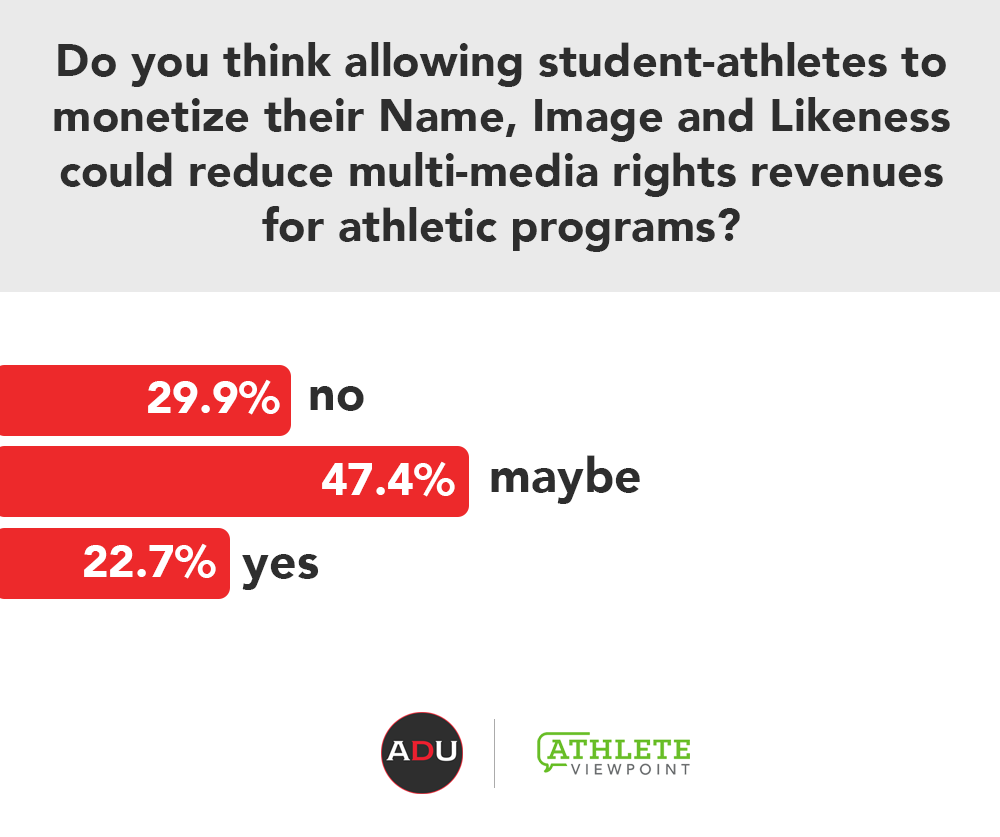

On the question of whether Name, Image and Likeness could lead to a reduction in multi-media rights revenues, ADs are again split, with about half unsure of the long-term effects. This is perhaps the biggest question mark associated with NIL – will student-athletes ability to monetize their own brands lead to them taking a piece of the existing pie of cash flowing into the industry, or will it help make the pie bigger?

As to whether Name, Image and Likeness can potentially lead to a reduction in compensation for coaches and administrators, 59.8% of ADs surveyed believe it will not. Among Power 5 and Group of 5 ADs, that number was even higher, with 64.3% and 76.2% respectively giving no as their answer.

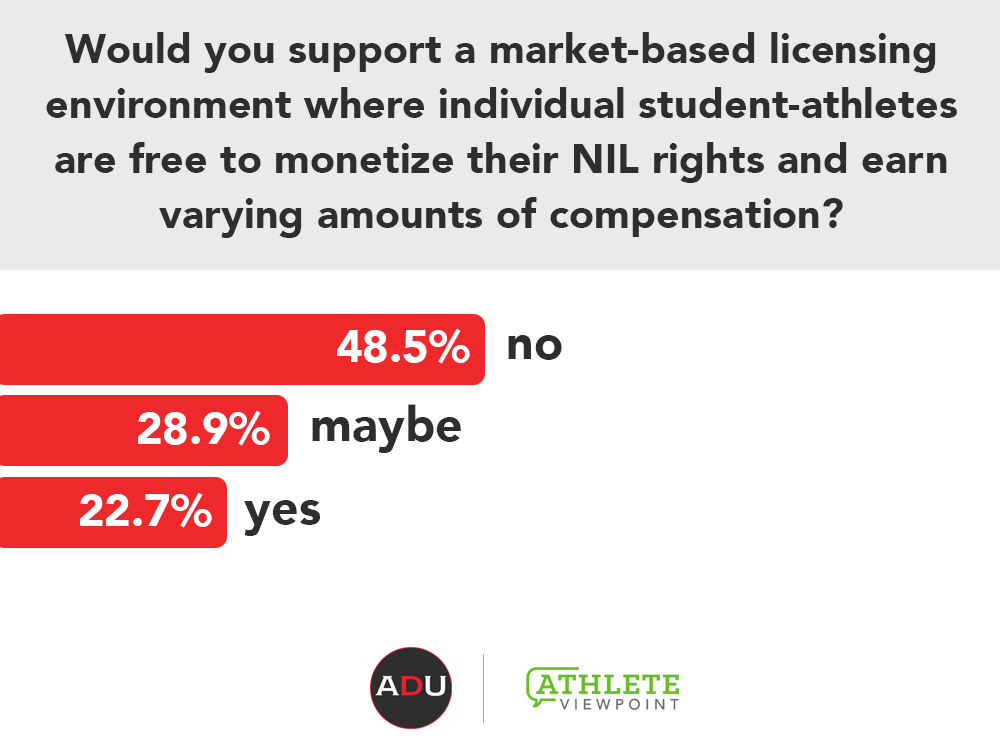

As to the question of whether a “free market” based system should exist in which all student-athletes would be free to monetize their NIL rights, ADs were split, with 49% overall saying they should not.

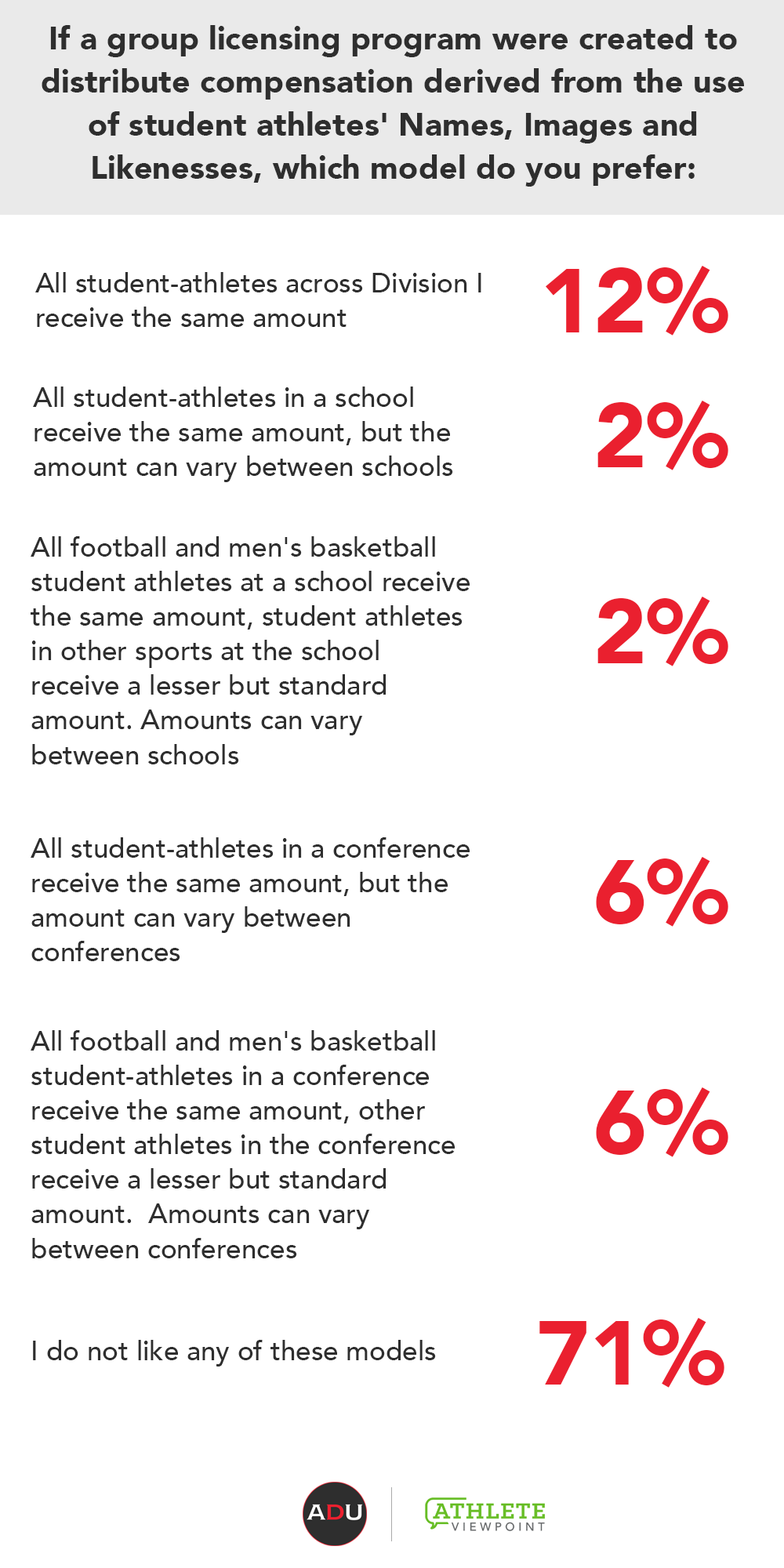

Not surprisingly, when given several models for a group licensing system that have been discussed by members of the media (rather than a free-market), the majority of ADs did not find any of them to their liking. This question, perhaps more so than all others, shows the complexity surrounding the implementation of NIL.

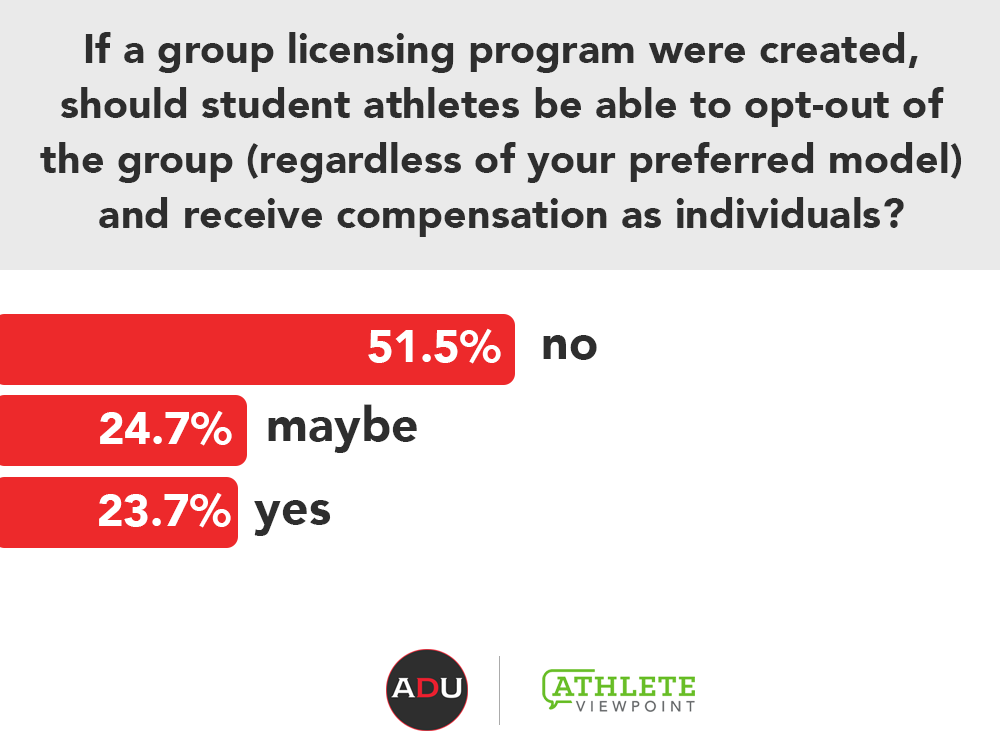

Administrators were again split as to whether if a group licensing program were created, whether student-athletes could opt out to pursue opportunities in the open market. This type of hybrid model would certainly be highly complex and difficult to regulate.

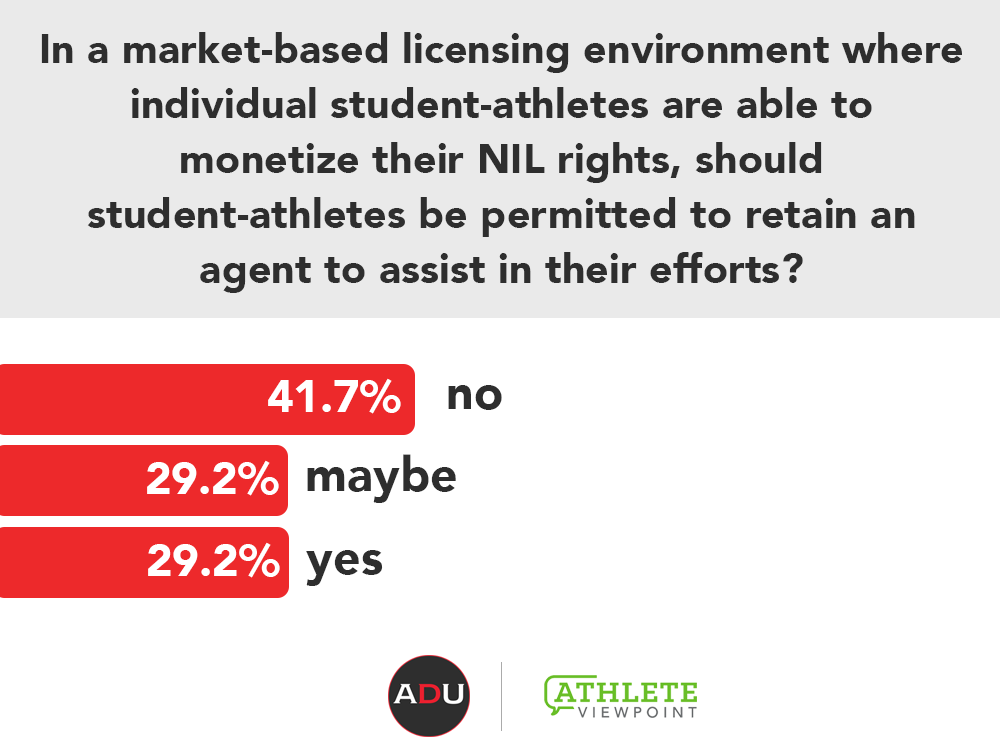

As to whether student-athletes should be able to hire an agent or representative in a free-market system, most ADs were in favor of the idea in some form. Approximately 78.3% of Power 5 ADs answered with a Maybe or Yes to the question.

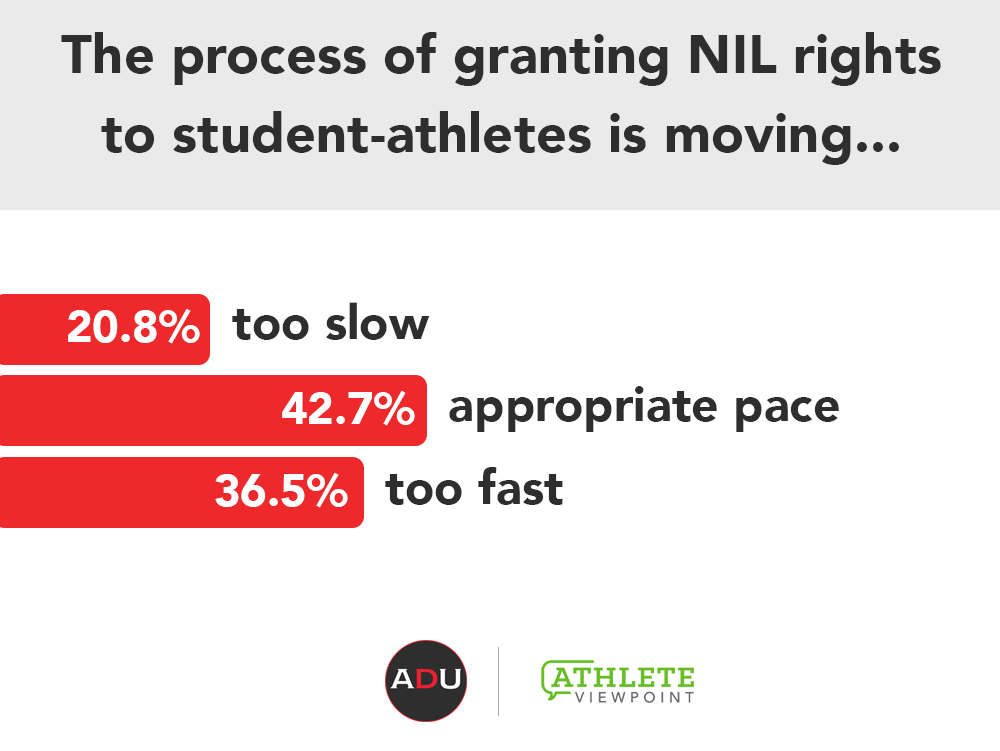

Lastly, a little over one-third of administrators feel that the NIL process is moving to quickly while many believe the pace is just right. AthleticDirectorU also requested ADs participating in the survey to provide commentary and prospective on the question of Name, Image and Likeness and student-athlete compensation. A selection of those comments can be found below:

——

It is unfortunate that much of the public’s understanding of NIL has been driven by the media, many of whom don’t necessarily have a good grasp on how various models would work or the complexities associated with those models. The media members that are most vocal about this topic remain those covering football and men’s basketball, as a consequence, the opinions of other sports are being left out of the equation. It’s important to remember that in any given year there are only a handful of athletes like Zion Williamson, Trevor Lawrence and Sabrina Ionescu that are likely going to be able to draw significant value from third-parties for their NIL rights. These student-athletes have market value that will be established through elite level performance at their particular schools. However, the majority of student-athletes, including those in football and men’s basketball, do not have a value above the cost of their scholarship and the services provided to him or her. Men’s basketball had 5,537 student-athletes participate in 2017-2018 and football had 15,606 at the FBS level. Are all 21,143 generating revenue for their particular school? That is a very difficult argument to make broadly across all of Division I. It is a very complex issue, but there’s no question it needs to be resolved.

——

Like anything else, the market should be allowed to have some say in what happens. By simply redefining “amateurism” in the NCAA rule book to mean that an athlete isn’t compensated by their institution, they could then monetize their own NIL without institutions being at risk. This would allow the market to decide their demand. This would create significant change, but this change will be better than letting lawsuits decide the future of the industry.

——

While I understand the NIL argument, it really only involves football and men’s basketball student athletes at power five institutions. Of course, there will be outliers, but the majority of SA’s earning revenue from NIL freedom would come from those two sports at the elite programs. Once permitted, what would we do to keep say Alabama, from paying their quarterback millions of dollars to use his face on posters and other advertising mediums? How does that shift of revenue impact Olympic sports, that are 100% funded from revenues generated by football and men’s basketball? We as administrators must start finding solutions to these questions, or it appears as though the legislators will end up doing it for us.

——

A group model would be a mistake. That will still not address the elite athletes’ right to fair compensation. A system that pays the projected #1 NFL pick 20% of his fair value as a paid endorser, and pays a women’s cross-country athlete 1000% of her fair value – does not address the elite athlete’s concerns. Take the endorsement/sponsorship dollars completely out of the scope of NCAA rules. There is no Title IX concern regarding what a car dealer pays to a football player to make an appearance at the dealership or on TV. It should go without saying that we also need to let these young men and women retain the services of an agent for these purposes.

——

——

I think the primary exacerbating issue is the extraordinary amounts of money that some coaches (and administrators) are making. Prior to the recent significant growth in salaries, there was much less concern about student-athlete compensation or exploitation. Throughout most of the history of college athletics – i.e., before the current economic paradigm – one could argue that NCAA amateurism rules were fair and worked effectively. In the current environment, there is too large of a disparity between coach compensation and student-athlete compensation. If we believe that providing student-athletes with more compensation runs counter to the educational values of college athletics, then we should figure out ways to re-balance by rolling back and limiting coach (and administrator) compensation.