2017 Was A Big Year in College Sports Law – Will 2018 Be Even More Significant?

2017 witnessed several key developments in the legal and business issues impacting universities and intercollegiate athletics. At the forefront is the recently-signed Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which will have financial implications for many of college sports’ top departments. The TCJA nearly overshadowed the FBI’s investigation into recruiting practices in men’s college basketball, an inquiry promising to profoundly effect the future of the NCAA’s crown jewel sport.

Further, the Supreme Court’s forthcoming decision in the Christie v. NCAA case could open the door for betting on collegiate athletics contests, something NCAA President Mark Emmert has said the Association will resist. The final month of 2017 also saw record numbers of coaching contract buyouts, with some of the payments owed to fired coaches surpassing $10 million. And looming in the background is the In re: National Collegiate Athletic Association Athletic Grant-in-Aid Antitrust Litigation case, more commonly known as the Jenkins case, which could turn amateurism on its head and forever alter the way in which college athletes are compensated.

Here is the 2018 outlook on these developments:

Taxes

While the TCJA will affect almost every level of the American economy, the final bill includes several provisions that will impact college athletic departments specifically. Let’s start first with a potential effect that was averted: In the House version of the bill, private activity bonds used by colleges and universities to finance, among other things, athletic facilities would have lost their tax exempt status, raising some $39 billion in additional taxes over the next 10 years. The Senate version of the TCJA left the private activity bonds untouched, which is how the bonds were ultimately treated in the final version of the bill.

TCJA’s main impacts on athletic operations comes via three provisions: One that charges a 21 percent excise tax on salary above $1,000,000 paid to employees of non-profit organizations (like universities or university athletic/booster associations); another taxing the capital gains of endowments; and another ending the deduction for season ticket donations.

Excise Tax

Under the TCJA, every dollar over $1,000,000 earned by an employee of a tax-exempt non-profit organization is assessed a 21 percent surcharge. The formula for calculating the surcharge is:

For a coach earning $2,500,000, this means $315,000 in taxes for the entity paying the salary. At the FBS level, there are 76 head football coaches earning $1,000,000 or more; when the 76 salaries are assessed for taxes and the numbers totaled, the result is approximately $35.9 million in additional taxes owed. Performing these same calculations for Division I men’s basketball coaches show schools will owe $13.2 million in new taxes. And these numbers underestimate the new tax burdens on university athletic departments because they omit the salaries of athletic administrators and assistant coaches, which can also stretch into the seven figures (especially in football).

All told, it is possible that collegiate athletic departments could incur upwards of $50 million in additional taxes under the TCJA. Many coaches and administrators are paid through external athletic associations, and so a portion of the burden may fall on those organizations. Still, athletic budget makers must account for these new expenses in their 2018-19 projections and determine whether it is necessary to shift resources across their departments.

Also of note here is the TCJA’s treatment of “pass-through” income (income that is earned by personal corporations and individual LLCs). Coaches and administrators may seek to establish personal LLCs and be paid through them to gain more favorable income tax treatment. Kevin Sumlin’s contract with Texas A&M incorporated this strategy, with some of the salary being paid directly to Sumlin and another portion being paid to Sumlin’s corporation, #YESSIR!, LLC. Speaking with tax experts, university counsel, and the coach’s agent may assist ADs in determining opportunities and challenges in this area.

University Endowment Tax

Also new in the TCJA is a 1.4 percent tax on the capital gains of the endowments of colleges meeting certain criteria. The institutions subject to this levy include Princeton, Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Rice, Notre Dame, and Richmond. Of these, Stanford – which maintains an endowment fund solely for athletics – may be affected the most. In 2013, the Cardinal’s athletic endowment was valued between $450-500 million, 5.5 percent of which was released for use each year. Now, any capital gains earned by the endowment will be taxed at 1.4 percent, or less than 2 cents on the dollar. So, if Stanford’s endowment grew $25,000,000 in one year, the taxes on those gains would total $350,000. Because athletic departments will have differing financial relationships with their institution’s endowment, the impact of this new tax will vary from school to school. ADs may find it helpful to speak with their school’s financial officials to determine the potential impact on their departments.

Season Ticket Donation Deduction

Perhaps the TCJA’s most concerning provision for ADs was its elimination of the tax deductibility of the donations many schools require prospective season ticket holders to make before having the opportunity to purchase season tickets. At present, the donations are tax deductible up to 80 percent, lessening the financial hit of seat donations that can often range into the five figures. For instance, under previous tax law, a donor could deduct $8,000 of the $10,000 donation required to purchase season tickets from his or her total taxable income (i.e., if the same donor had $100,000 in taxable income, it could be reduced to $92,000). Now, that deduction is gone.

Prior to the bill being signed, some institutions worked to take advantage of the deduction for as long as possible by offering season ticket holders the option to pay the required donations for future years now. Because giving is often deeply personal and driven by a number of different, individualized factors, it is difficult for ADs and their development staffs to generalize on how the loss of the deduction may impact ticket sales. To gauge the potential impact of these changes heading into the 2018-19 sports seasons, athletic departments can continue the ongoing work to understand the motivations of their season ticket holders – which may help determine whether the required donation is now beyond the individual’s reservation price.

FBI Investigation

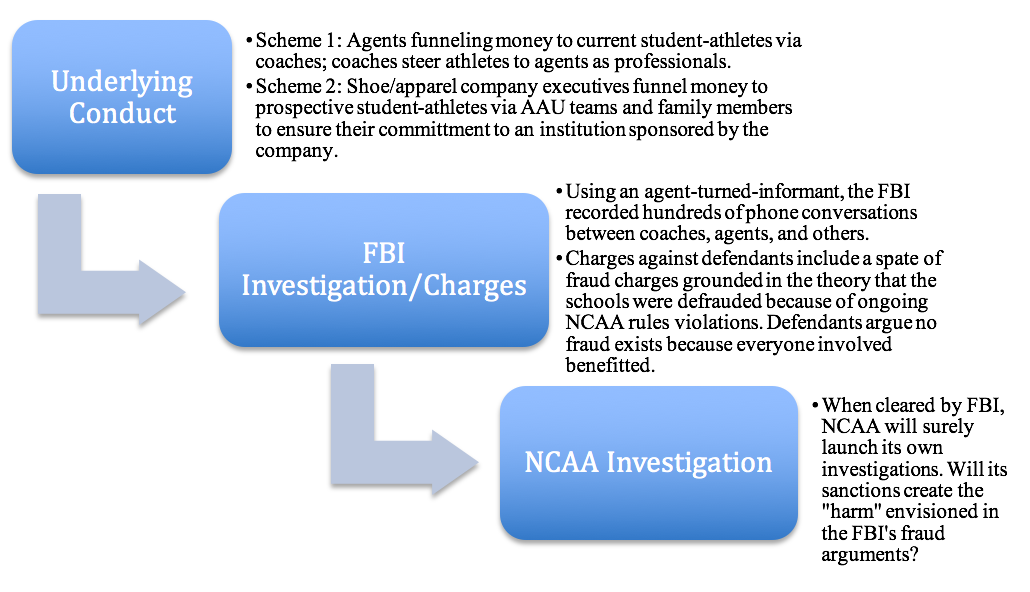

Prior to the TCJA, the story gripping college sports was the FBI’s investigation of recruiting practices in men’s basketball. Probing the “dark underbelly” of college basketball, the FBI uncovered two major payment systems: One in which financial advisors and agents funneled money to college coaches with instructions to steer current athletes to those advisors and agents when they turned professional, and another in which apparel company representatives paid high school athletes (with the money passing through amateur basketball leagues and family members) to attend an institution sponsored by the same apparel company. These revelations were made in September after a nearly year long investigation. The defendants have urged the court overseeing the case to dismiss the charges, arguing their acts benefited – not defrauded – athletes, coaches, and schools. With the FBI still investigating the ties between agents, advisors, coaches, and players, it is important for ADs to understand both the challenges and opportunities presented.

Unlike the NCAA’s enforcement process, which is administrative in nature, the FBI is conducting a criminal investigation. That has several implications for institutions, including in the evidence-gathering process. While the NCAA has rules requiring schools to cooperate with investigations, there is no legal duty to do so. The FBI, on the other hand, can issue subpoenas, compel testimony, secure wiretaps, and utilize other investigatory tools simply not at the disposal of the NCAA. Failure to comply with subpoenas or giving untruthful statements under oath could result in far more than just NCAA sanctions: Criminal and civil convictions, large fines, and jail time are all possibilities. It is critical that ADs educate themselves and their coaches on differences in their obligations with respect to the FBI’s inquiry. Consulting with university and personal counsel could be helpful in this regard.

But with these challenges come opportunities. As has been demonstrated at Louisville, costly contract disputes can arise when schools move quickly to oust coaches and administrators involved in scandals. While most coaching contracts include provisions on NCAA investigations and sanctions, the FBI’s inquiry shows that the NCAA need not be involved for a coach’s actions to land the institution in hot water. Given the money at stake, ADs may find it worthwhile to review their coaches’ contracts to ensure that language addressing criminal investigations – even those in which the NCAA is not a party – is included as a basis for “for cause” firings. This would make the process of removing a coach involved in such an investigation simpler and far cheaper.

Finally, there remains the question of how the Rice Commission will factor into the legacy of this trying chapter in the NCAA’s history. The Commission, formed in the aftermath of the FBI’s press conference announcing the investigation, is chaired by former Secretary of State and College Football Playoff Selection Committee member Condoleezza Rice and also includes former players Grant Hill and David Robinson, two currents ADs and one former AD, and Martin Dempsey, the Chairman of USA Basketball. NCAA President Mark Emmert has said, “fundamental change with the way college basketball is operating” is needed prior to the start of the 2018-19 basketball season, giving the Commission less than a year to suggest major overhauls to the current landscape. At this point, there are understandably far more questions than answers: Will amateurism be tweaked or changed, and if so, how and to what degree? How can the NCAA influence the NBA’s draft eligibility (“one-and-done”) rule? What the impact of federal intervention and possible legislation be on the NCAA’s enforcement structure and mechanisms?

The Future of College Basketball

Although it’s difficult to determine best and worst case scenarios at this juncture, convictions and strong, criminal penalties on the defendants may deter the type of behavior uncovered by the FBI. A lack of federal or NCAA punishment may have the opposite effect. On the other hand, the Rice Commission has the opportunity to help the NCAA strike a better balance between amateurism and permitting athletes to profit from their names, images, and likeness. Entrenching amateurism or enhancing the NCAA’s investigatory powers may do little to solve the problems facing men’s college basketball and the NCAA as a whole.

Sports Gambling

A win for New Jersey in the Christie v. NCAA sports betting case (a likely outcome given the tone of the oral argument) could give states the authority to determine whether to allow sports-related gambling within their borders. Given the ever-increasing appetite for tax revenues and the fact that many states have already moved to legalize and regulate daily fantasy sports, it seems likely many states would expand sports betting should the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA) be struck down. A decision from the Supreme Court should come by the end of March.

Best case scenario: For NCAA President Mark Emmert, it is a Supreme Court ruling in favor of the NCAA and PASPA. Power 5 conference commissioners, however, have been non-committal on their position if sports betting were to be expanded.

Middle case scenario: The Supreme Court permits New Jersey to proceed with the repeal of its sports gaming regulations, but still upholds PASPA as constitutional. In this scenario, other states would be have to undertake legislative action (as New Jersey did) to possibly institute sports gaming in their jurisdictions – and face potential legal challenges along the way.

Worst case scenario: New Jersey wins, PASPA is struck down, states begin implementing sports betting and Emmert cannot build consensus amongst the membership on whether to embrace or resist sports gambling.

Coach Contracts

The Christie oral argument was held on December 4th – right in the middle of what was one the most head-spinning coaching carousels in recent memory. All told, $70-plus million in buyouts will be paid to fired college football coaches, including over $10 million each to Todd Graham (Arizona State), Kevin Sumlin (Texas A&M), and Bret Bielema (Arkansas). Unlike Bielema, however, Sumlin and Graham’s buyout figures will not be reduced by payments from future jobs. This lack of “mitigation,” or offset language, could cost these schools millions. But because the current coaching market may be shifting toward contracts with no offset provisions, ADs may not have leverage to change to negotiate these clauses into their coaches’ contracts.

Grant-in-Aid Litigation

And if all that wasn’t enough, the NCAA also faces what likely will be its most important court battle to date when In re: National Collegiate Athletic Association Athletic Grant-in-Aid Antitrust Litigation (commonly known as the “Jenkins” or “Kessler” case), goes to trial in 2018. The players desire a system in which schools make their own, independent decisions on how and to what degree to compensate their athletes. The NCAA’s lawyers have defended the current amateurism rules, arguing the precedent set in the O’Bannon cases does not permit players to be paid more than a scholarship covering cost of attendance.

Best case scenario: The Court finds the decisions in O’Bannon prevent the players in the Jenkins case from seeking a free market for their services.

Worst case scenario: The players prevail, and schools are permitted to compensate athletes above and beyond their cost of attendance. While a win for the players is far from certain, it may be wise for institutional leaders, including presidents/chancellors, faculty athletics representatives, athletic directors, and coaches to assess their collective priorities and values with respect to athletics, their financial means, and the mood of the athletes. Discussing these issues may assist institutions as they determine whether or not to compensate their athletes at higher-than-current levels, should the Jenkins court allow them to do so.

Conclusion

These five issues have the potential to fundamentally alter the operation of college athletics for the foreseeable future. And their effects may spread even further: From the TCJA to the FBI, athletic directors are now tasked with having at least a working understanding of tax law, criminal law, and variety of other legal and business disciplines that may have been on the periphery in eras past. Now, ADs with backgrounds in law and business can become even more valuable as their institutions navigate the new landscape. It will be telling to track if and how these developments keep the AD carousel spinning as universities seek to install new leadership for their athletic departments. Of course, we’ll follow these and other developments in collegiate athletics on Twitter and beyond.

Glenn M. Wong is the Executive Director of the Sports Law & Business Program and Distinguished Professor of Practice – Sports Law at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law.

Cameron Miller is a 2017 graduate of the Sports Law & Business Program and currently works at the law firm Lieff Cabraser Heimann & Bernstein in San Francisco, CA.