In 2019, Dr. Kevin Blue, then-University of California-Davis Athletic Director, penned a piece for ADU called the Rising Expenses In College Athletics And The Non-Profit Paradox. In his article, Blue described the structural challenges surrounding the growing expenses in big-time college athletics.

He noted three economic components that inform athletic directors’ financial decisions: A non-profit organizational structure, zero-sum competition, and accelerating revenue.

First, Blue highlighted the non-profit organizational structure of college sport. Athletic departments don’t have owners looking for a return on investment, and thus, sport leaders are not inclined to operate with the goal of turning a profit. With this, economic decisions are informed based on college sport missions, supposedly things like athlete development, gender equity, academic primacy, and long-term sustainability. Financial decisions are also—arguably predominantly—based on winning. Thus, because college sport is a non-profit, when revenues continue to rise, as we’re seeing right now, expenses simultaneously increase in order to achieve the mission(s).

Second, Blue discussed college sports’ zero-sum environment: One team or program must win, and thus, another must lose. The competitive and zero-sum design of intercollegiate athletics creates what Blue called “an insatiable desire for an athletics program to make investments that drive success in the competitive part of its mission.” The drive to win thus increases departmental expenses.

Third, Blue described the trend of accelerating revenues in college athletics, something other non-profit fields do not similarly experience. Once again, since the non-profit mission of college athletics is not to create return on investment or generate surplus revenue, as revenue accelerates, so too do expenses.

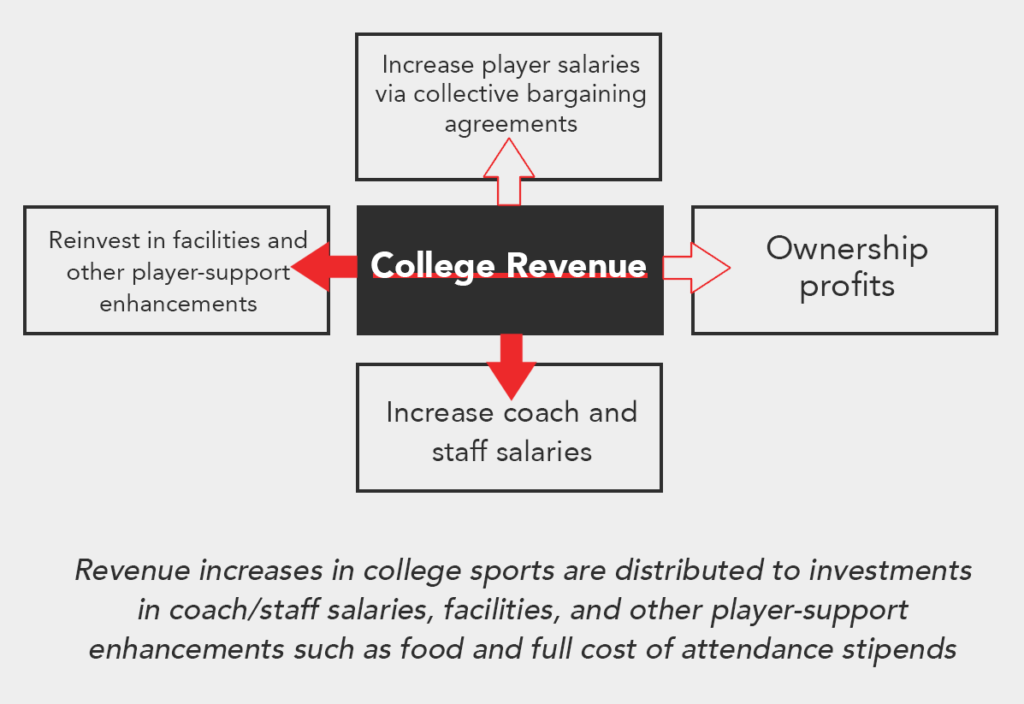

He concluded these three factors pressurize expenses, increasing departmental spending. And because of the design of college athletics, in 2019, expenses were allocated to two areas: increases in coach and staff salaries, and investments in player support enhancements and facilities. See Blue’s Figure 1 below.

In this way, college sport was financially distinct from its professional sport counterpart. Keyword being was.

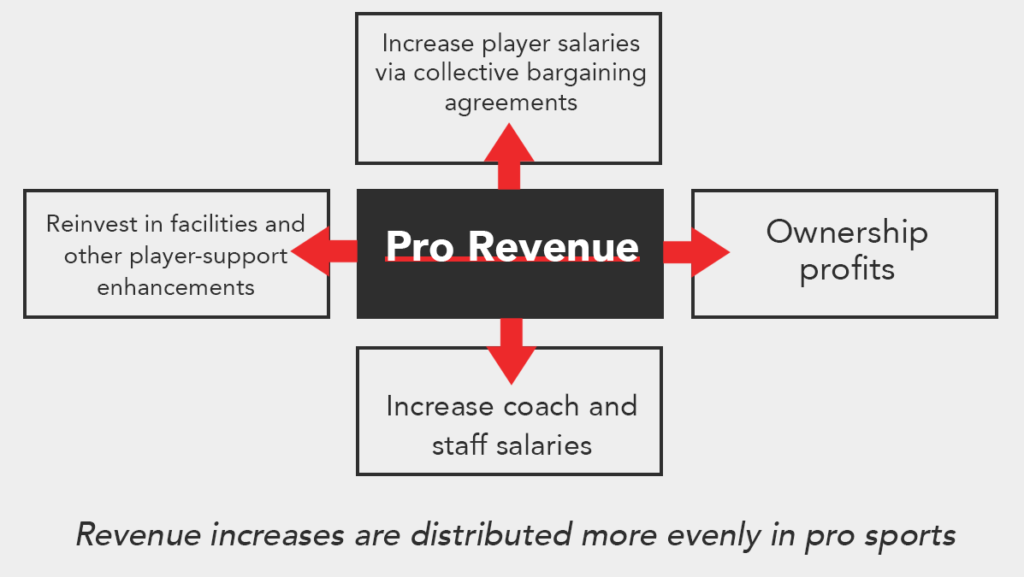

Now, college sport is not all that financially distinct from professional sports. Blue’s Figure 1 shows two unfilled arrows pointing to ownership profits and increases in player salaries via collective bargaining agreements. In recent weeks, significant movements in college athletics—the spark of private equity and the settlement of House v. NCAA—have helped fill in those arrows. See Blue’s Figure 2.

College sport still does not have true “owners” of athletic departments expecting financial returns. However, the introduction and growth in private equity’s presence in college athletics comes pretty close. Recently, Sportico and other outlets broke news of investment funders’ interest in supporting college athletic departments with as much as $2 billion. In lending this money, private equity investors and their firms expect a return, a share of the new revenue generated from the collaboration.

So, athletic departments and sport leaders may not just be making financial decisions based on the non-profit “mission” as Blue sees it, but also potentially on the return to private equity lenders. Such decisions also align with a more for-profit rather than non-profit model. In fact, Casey Schwab, CEO and founding partner of Altius Sports Partners, expressed in an interview that private equity changes college athletics’ “North Star a couple degrees towards for-profit interests.”

Similarly, while employment and collective bargaining rights were not central to the House settlement, it does allow for direct player compensation, akin to player salaries. Player payment and revenue sharing stems predominantly from television/media rights deals. Starting in fiscal year 2025-2026, the House settlement enables athletic departments to share up to $22 million annually with athletes. This, coupled with the potential for NIL deals to move in-house within athletic departments, leads college athletics to more closely resemble its professional sport peers. Similarly, if all college athletes become reclassified as employees, this professionalized model is further bolstered.

The other arrows for Blue’s model remain in college athletics, but given the significant and recent shifts, are likely to change. As expenses in the categories above continue to rise, it is possible, if not probable, that the expenses distributed to coach and staff salaries and player support enhancements and facilities may decrease. This may be necessary to meet the significant demands in the other expense categories.

Indeed, in the zero-sum competition that is college sports, or really all sports, it’s reasonable that more money would be distributed to college player “salaries” (i.e., NIL deals, revenue-sharing, etc.) compared to coaches’ salaries, as is done in professional sport models. A similar divestment in facilities and player support enhancements in favor of other funding strategies is also likely to continue.

While the field increasingly aligns with the professional model, this framework does not have to be the default for college athletics. The question is, will the NCAA, policymakers, ADs, and the athletes themselves step into this moment of opportunity to create and implement a sustainable and stable model?

Blue concluded his piece in 2019 noting, “financial decision-making in college sports has been perfectly rational within the structures of the current system.” Blue’s system, however, no longer exists–except for the rising expenses.