The under-representation of women athletics administrators is not a new realization, as researchers and administrators have long noted the lack of female leaders within the NCAA. Even though the NCAA formalized the Senior Woman Administrator (SWA) designation in 1981, women remain underrepresented in leadership positions. For example, the 2010 NCAA report listed 32 female Athletic Directors (ADs) in Division I, which represents roughly 9% of ADs at that level. Furthermore, Associate Director of Athletics were 30% women and Assistant Director of Athletics roughly 28% women. If the intent of the creation of the SWA position was to increase female leadership in the NCAA, why have we not seen a dramatic increase in women in other top athletic department roles?

To investigate this question, we conducted a study comparing leadership networks in the NCAA—specifically, those of SWAs and athletic directors. Our study is based on prior research that demonstrates that interpersonal relationships and social environment affect both leadership emergence and effectiveness. Reaching a position of leadership is not merely the consequence of individual attributes or abilities, but rather a phenomenon influenced by the web of relationships within which an individual operates. To understand the influence and effectiveness of SWAs and ADs, then, requires an analysis of their networks: the people and organizations to which they are connected.

Within sport management, previous researchers have long cited the influence of the “old boys’ network” in the NCAA as a barrier for women striving to reach leadership positions. To our surprise, we were unable to find any research examining the actual networks of NCAA leadership positions; instead, the literature presents mentoring, hiring practices, and social networking as evidence that such a network exists. A network, however, is more than having a mentor, mingling at social events, or even who hires whom. Studies of networks include social structures, relationships among actors, and the influence of social structure on individual attitudes, outcomes, and behaviors. At a minimum, a network study examines some set of social actors, the relationships among them, and the resulting structure based on those ties.

Our study, then, examines the networks of ADs and SWAs by examining the affiliation ties between individuals and organizations. We collected the employment and education history of SWAs and ADs working in NCAA Division I athletic departments to establish affiliation ties: when two people share an alma mater or worked in the same athletic department, they are connected in the network. Each connection may not represent a realized friendship, but sharing such ties has been linked to increased information flow, access to job openings, and other positive outcomes related to career advancement.

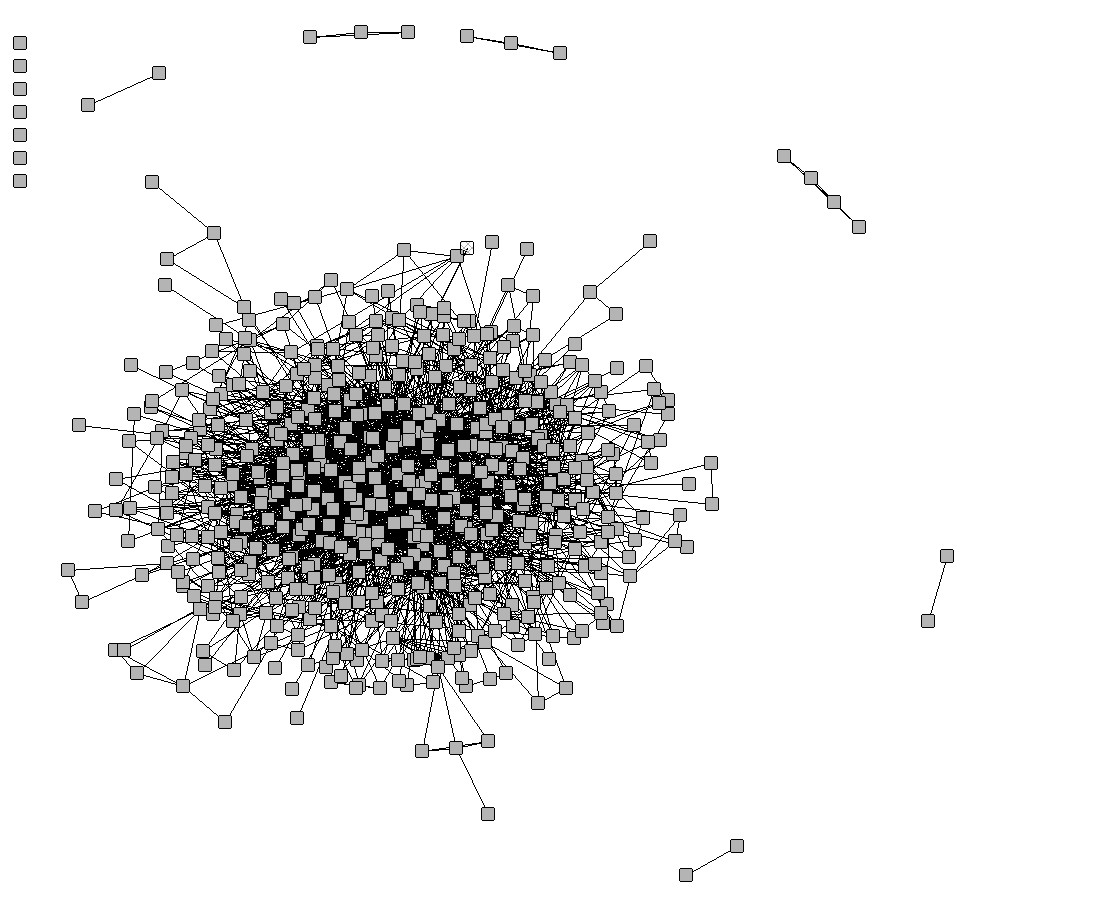

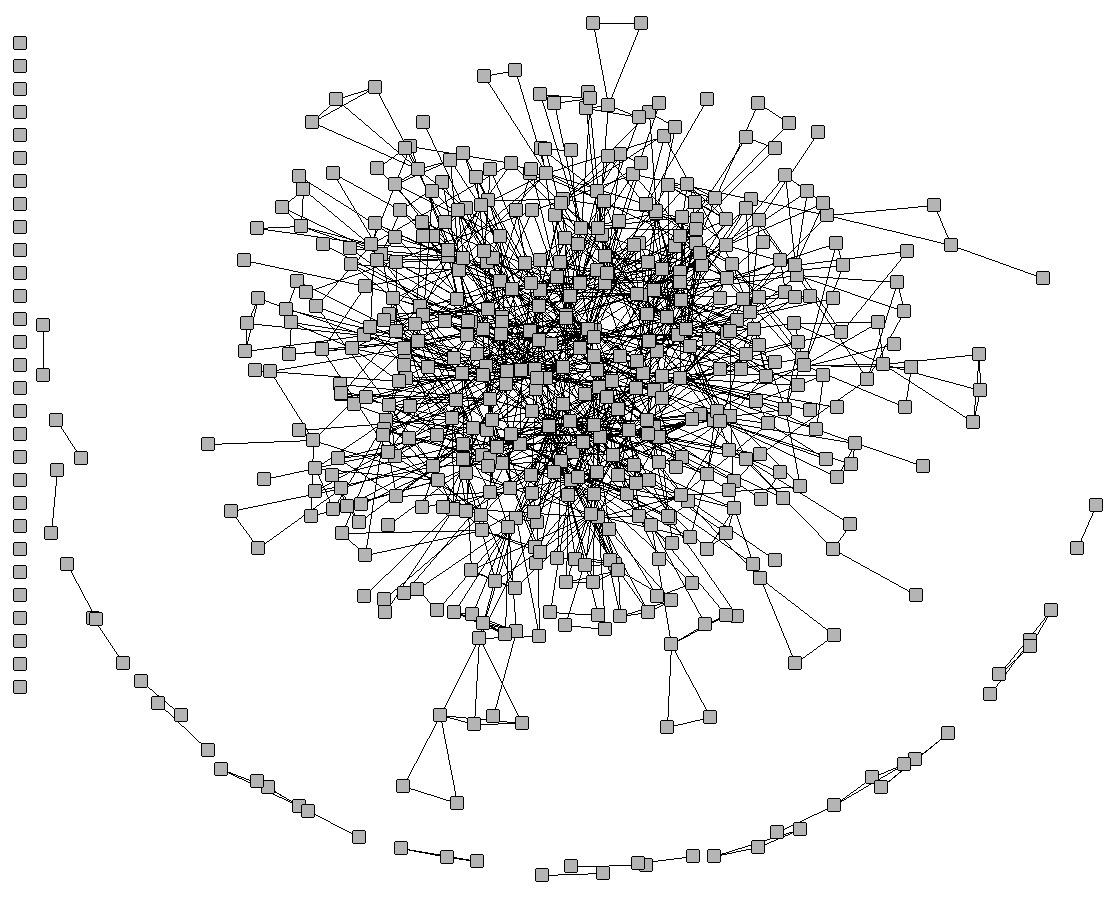

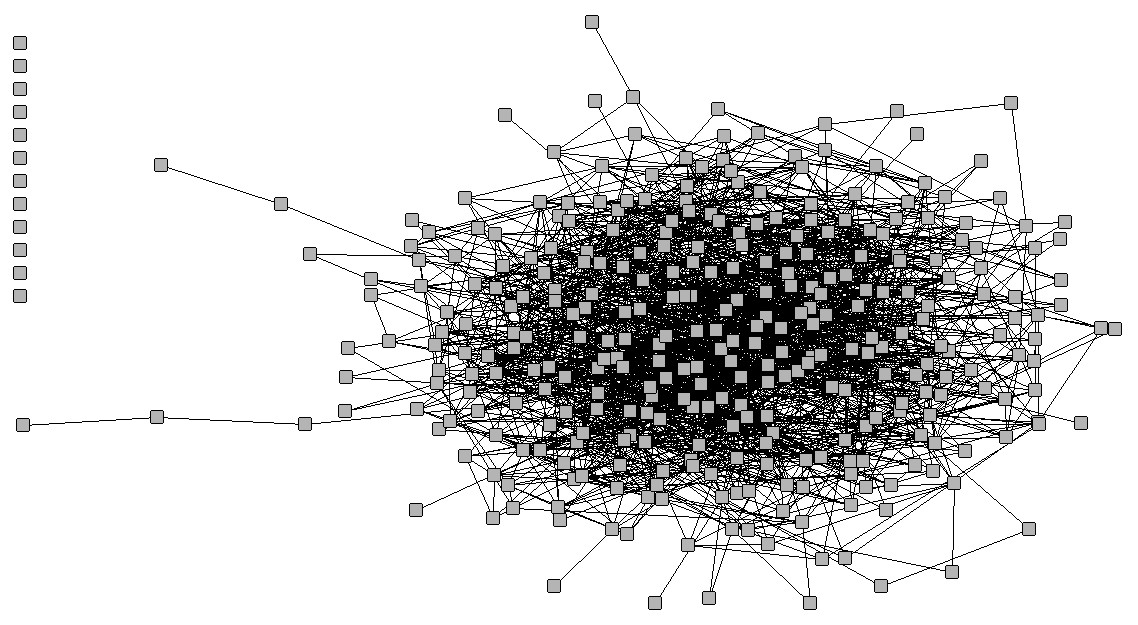

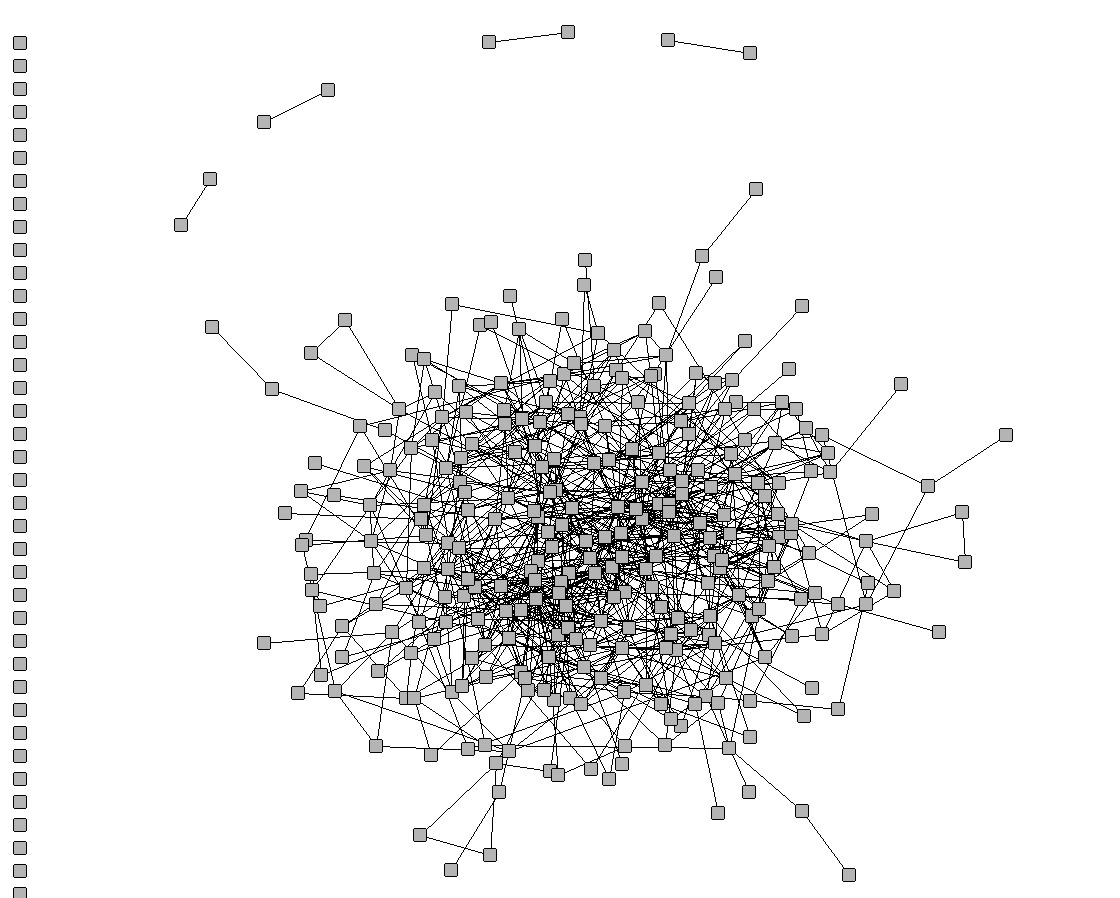

With this affiliation information, we used network analysis software to create four networks: person-by-person networks of ADs and SWAs, and organization-by-organization networks of ADs and SWAs. Immediately, differences between the AD and SWA networks were visually obvious: the AD networks were much denser, indicating a greater number of ties and interconnectedness between members, than the SWA networks. Diving into statistical analyses of these networks confirmed the visual evidence of structural differences between these networks (see the full published manuscript of our study for the visual representations of the networks and a full analysis).

AD Organization-by-Organization

SWA Organization-by-Organization

AD Person-by-Person

SWA Person-by-Person

The AD network, which predominantly includes males, was far more cohesive (interconnected) than the network of SWAs. In cohesive networks, information is more likely to spread and members have greater access to best practices, job openings, and other important information. The inverse is also true; fragmented networks provide individuals with fewer opportunities to access information from other members of the network. The cohesive AD network affords its members with constant access to information and other interpersonal exchanges that allow members to reach and solidify leadership positions. Whether this means new job openings or gossip, members in cohesive networks can more efficiently access such information. The AD networks possessed such characteristics while the SWA networks simply did not.

If the SWA is supposed to represent the women’s version of the “old boys’ club”, our research suggests it may not be very effective in combating the lack of women in leadership positions on its own. This is not to say SWAs cannot reach the position of AD; rather that when such a promotion transpires it is less likely to result from the SWA network. Moreover, the SWA network had a high number of “isolates”, or members who share zero affiliation ties with other members of the network. Isolates are entirely disconnected from the rest of the population; they receive none of the resources available through a network of colleagues.

In the AD network, 12 of the 341 actors were isolates; for SWAs, that number was 35. The large number of isolates suggests that in some organizations, the SWA position represents an obligatory woman on the leadership team, where individuals are promoted but hold limited influence because they are not socialized and entrenched in the network of their peers. Appointing women to token leadership positions where their voice may be limited by structural limitations may do more harm to the overall progression of future female leaders given how isolates weaken the overall structure of the SWA network. An isolated SWA suggests women may have a seat at the proverbial leadership table within the NCAA, but no real voice.

Whereas the SWA network was largely fragmented, the AD network was highly cohesive. When the 12 isolates are removed from the AD network, the remaining 329 ADs were all connected. Information travels efficiently and resources are easily accessible in such connected networks, providing great value to the members within the network. The interconnectedness is equally problematic for those restricted from the network – such as women. While women made up roughly 10% of the AD network, of the 25 most “influential” people in the AD network, only one was female. Moreover, women were over-represented on the periphery of the network and were over-represented among the isolates based on what chance alone would suggest. In other words, there does seem to be strong evidence of an “old boys’ club” within the AD network.

While the person-by-person networks examined ties between individuals based on shared connections to organizations, the organization-by-organization networks represented the ties between organizations based on a shared connection to a common person within the network. Analyzing such networks also allowed us to consider which organizations hold the most influence and power. For instance, if a great number of ADs or SWAs worked for or went to school at a particular institution, that institution would be considered influential within the respective network. Here too, we found interesting differences between the ADs and SWAs, starting with the 10 most popular and influential organizations within each organizational network.

The most noteworthy finding involved working for the NCAA: within the SWA network, the NCAA was the most popular influential organization, yet it did not rank in the top 10 for ADs. SWAs, then, seem to gain professional legitimacy through an NCAA affiliation, something that does not appear to be as needed while on the path to AD. One other interesting takeaway from the organizational network was the signaling of academic degrees, as the two oldest sport management programs (UMass, Ohio University) both reported top five scores in the AD network and UMass had the second highest in the SWA network.

The findings of this study broaden our understanding the networks of ADs and SWAs and reinforce the notion that informal networks matter in reaching leadership positions in the NCAA. Moreover, the gendered nature of leadership networks appear to play an important role in the underrepresentation of women in NCAA leadership positions, with the less connected, all female SWA network indicating less access to information compared to the more connected, mostly male AD network.

While we knew there were a small percentage of women in the AD networks; we did not realize they would be largely relegated to the periphery of the AD network. Similarly, we assumed going into this study the SWA network would be less cohesive than the AD networks; we did not foresee such a substantial difference between the two networks, particularly with the discrepancy in isolates between the networks.

We have now presented this data at academic conferences and published this research–and each time we conclude with the same sentiment. After working with these networks and detailing their gendered nature, we are left with a somewhat uncomfortable conclusion. Aspiring leaders are often instructed to utilize their informal networks for jobs, personal recommendations, or other resources to advance their careers. For both students and young professionals, suggestions about leveraging “who you know” are rampant in recommendations for career advancement. Yet–and this is perhaps the most important conclusion of our research–if the informal networks of SWAs and ADs are exclusionary and largely gendered, staying within one’s informal networks reproduces a system of gendered discrimination.

If those in leadership positions share news of potential job openings or provide advice on best practices with their own informal networks, they are indirectly (and in all likelihood unknowingly) fostering a system of gendered discrimination. Such a realization may appear harsh to some, but it reflects a conclusion strongly supported by our research into the networks of ADs and SWAs.

So what can we do this information? Organizations could consider formal mentorship and networking programs that include women and strategically connect them with the informal networks from which they are largely excluded. A formal AD-to-SWA mentorship program with an AD outside of their home institution would provide SWAs the opportunity to increase their informal network, twofold. In addition, workshop sessions at the NCAA Convention, centered on SWAs advancing to AD positions, would be another opportunity for women to permeate AD networks.

If organizations are serious about increasing diversity and opportunities for women in leadership positions, they must be cognizant of the gendered biases present in their personal networks, and consciously consider women, most of whom will be outside of their network, for leadership positions.

This article is based on Katz, M., Walker, N. A., & Hindman, L. C. (2018). Gendered leadership networks in the NCAA: Analyzing affiliation networks of Senior Woman Administrators and Athletic Directors. Journal of Sport Management, 32, 135-149.