Kansas State professor Lisa Rubin determined that “No single pathway or training regimen leads directly to a position in the field” of athletic academic advising, according to an article she published in 2017. Her data showed that most advisors have a masters, the majority majored in fields like sport management, counseling or higher education, and about half played a college sport.

We decided to build on the information from Rubin’s 2017 questionnaire by looking at whether the work conditions of advisors, such as how many teams they advise, or their backgrounds, such as whether they played college sport, varied by the type of NCAA Division I athletic department they advised for. We used the categories “Power Five”, “Group of Five”, Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) and athletic departments with “no football” (NFs) as the types of Division I athletic departments. During 2021, we sent out a survey through the National Association for Academic Advisors of Athletics (otherwise known as N4A). 413 advisors responded with results that we could use. In some cases, the background of advisors or their work conditions changed based on the type of Division I athletic department they worked for, and in others, there was little to no difference. Here are a few of the trends that we observed.

Some Trends Haven’t Changed Drastically In The Last Five Years

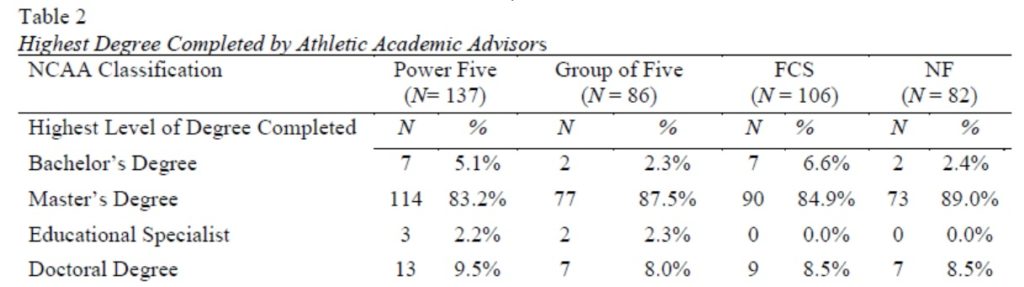

The vast majority of advisors still hold masters degrees. If anything, this has become more common. At least 95.6% of advisors reported that they had a masters degree. Just under 10% of advisors had a doctoral degree.

Also similarly to Rubin’s results, over half of advisors reported that they played a college sport at the NCAA, NAIA or junior college level, with two-thirds of those playing on a Division I team at some point in their career.

As far as highest level of education or college athlete experience, this was one area where no type of Division I athletic department was more likely to have more advisors that were former athletes with an advanced degree. Since so many advisors held masters degrees, it seemed unlikely that any one type of Division I athletic department would have an advantage in that area.

The important takeaway, other than there are not significant changes from 2017, is that potential athletic academic advisors should attend graduate school, and since the majority of advisors played a college sport, former athletes who are interested in becoming an advisor should feel encouraged that their experience could help them land a job in that career field.

The Race And Gender Of Athletic Academic Advisors Does Not Vary By Type Of Division I Athletic Department

A study published by Angela Lumpkin, Regan Dodd and Lacole McPherson found that women and racial minorities are underrepresented in several staffing areas within athletic departments, but that academic advising is an exception. This is an area, however, where the number of women or racial minorities can vary by the type of athletic department. The study written by Lumpkin also observed that women are more likely to obtain athletic academic advising positions at Division I athletic departments without football programs. We were interested to see if women or racial minorities are more or less likely to work as athletic academic advisors at a certain type of NCAA athletic department. Based on our data, this was not the case. We do have data in another project regarding whether women or racial minorities are more likely to advise certain types of sports; however, the study is under review.

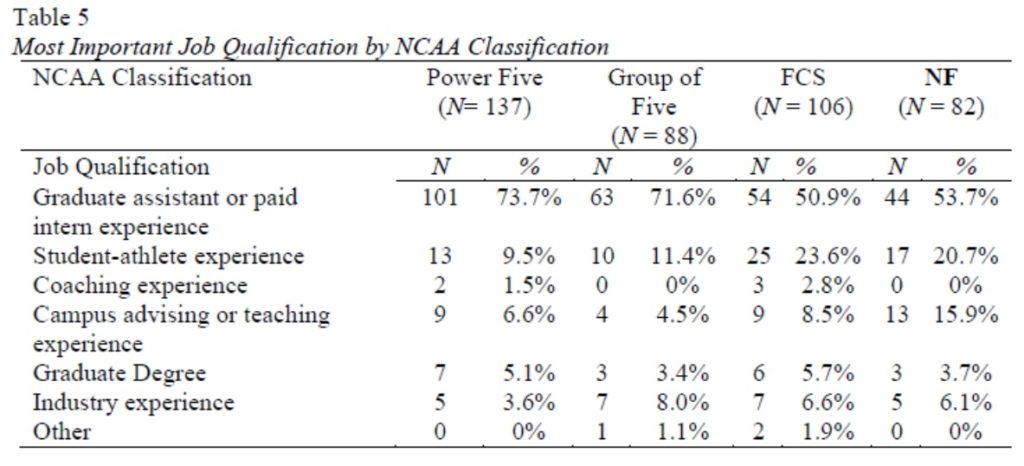

Former Coaches Are More Likely To Work At The FCS Level

So far, we have made it sound like there isn’t much of a difference in the advisors at FCS or NF athletic departments compared to Power Five or Group of Five, but there were a couple areas with noticeable gaps. The advisors at Power Five and Group of Five athletic departments were significantly more likely to have worked as a graduate assistant or paid intern in athletic academic support. FCS athletic departments, however, hired more former college coaches. It is important to point out that the advisors in our study only reported what type of work they did before becoming an advisor. We did not ask them what type of backgrounds that they, or other administrators, wanted when they hired an advisor. Power Five and Group of Five institutions might be hiring the most desired candidates with relevant graduate assistant experience, and as a result, there may be less of these candidates available for FCS athletic departments. Another possibility is that FCS athletic departments simply prefer to hire former coaches. This is a topic that could be studied by other researchers.

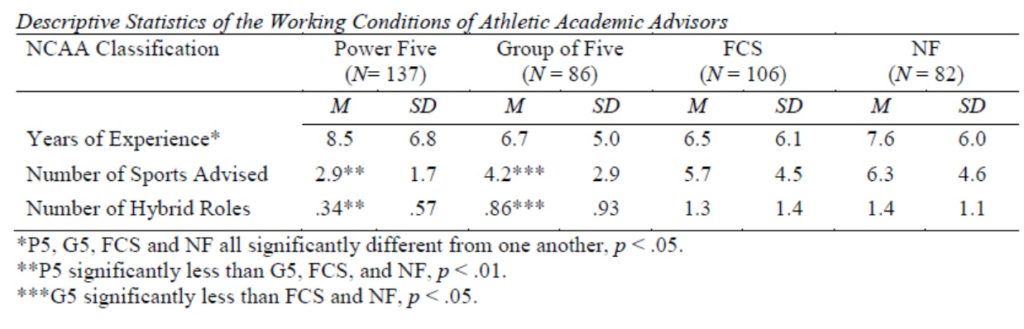

Advisors At Power Five Athletic Departments Have Less Job Duties

Advisors at Power Five athletic departments advised less teams than advisors at Group of Five athletic departments. The same applied to advisors at Group of Five athletic departments compared to FCS and NF athletic departments. The advisors at Power Five athletic departments, compared to those in Group of Five, held less “hybrid roles”. This means that they had less job duties outside of advising, such as working as a learning specialist. The same went for Group of Five athletic departments compared to those in FCS and NF athletic departments.

We should not necessarily assume that the advisors at FCS institutions and athletic departments without football have a higher workload, since we did not ask advisors to estimate how many hours they worked per week on average. Also, the number of teams an advisor oversaw does not clarify how many athletes they advise, since the size of a team’s roster varies by the sport. The data does suggest that advisors who want to focus on a specific role should try to work for a “Power Five” or “Group of Five” athletic department, and those that may want a wider variety of work should consider FCS or NF athletic departments.

Relevant Work Experience Is The Best Path Into The Advising Profession

While we were not shocked by this result, it was noteworthy just how strongly that advisors agreed that relevant previous experience, meaning experience as a graduate assistant or paid intern in athletic academic support, is “the most important job qualification” for potential advisors. The advisors at FCS and NF athletic departments were twice as likely to choose experience as a college athlete over being graduate assistant or paid intern compared to advisors at Power Five and Group of Five athletic departments, but even half of those advisors thought that relevant previous experience was the most important qualification. Working as a graduate assistant or paid intern might not be practical for adults who currently work in a full-time position and may want to become an advisor, but our data suggests that students who want to become advisors need directly related work experience. There were some advisors who voted for other answers such as “coaching experience”, “campus advising or teaching experience”, or “graduate degree”, but they were few and far in between. Only three voted for “other”, so we are confident there was not an extremely important background characteristic we missed in our questionnaire.

A Few Quick Points

There are some other noteworthy takeaways from our data. First, some other researchers have used Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS), FCS and NFs as their types of Division I athletic departments. Although American Athletic Conference commissioner Mike Aresco might disapprove of our use of “Power Five” versus “Group of Five”, our data showed a few significant differences between the two types of athletic departments.

Second, only a few advisors had experience competing at either the Division II or Division III level. Since advisors indicated that experience as a college athlete was the second most important characteristic to becoming an advisor, behind being a graduate assistant or paid intern, athletic departments who are searching for graduate assistants or paid interns could broaden their candidate pools by recruiting former athletes from the institutions that compete at this level.

Third, advisors have shared in previous research that they believe a higher workload increased their chances of experiencing burnout. If advising a higher number of teams or being more responsible for more job duties in a “hybrid role” results in more work hours, then advisors at FCS and NF athletic departments may be more susceptible to burnout.

Finally, this study provides more evidence regarding the advantages that Power Five institutions, and to a lesser extent, Group of Five, have over the rest of Division I. Power Five advisors have more years of work experience as advisors, advise a lower number of teams, and are less likely to serve in “hybrid roles”, although they had no advantage in a few areas like educational background. If these additional responsibilities are more demanding, then this is just one more of the many advantages “Power Five” athletic departments have.