Playing intercollegiate sports is an amazing experience. Each year, over 480,000 collegiate student-athletes compete in 90 sports (men’s and women’s sports counted separately) at over 1,000 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) member institutions. Playing a college sport affords these hundreds of thousands of young men and women the opportunity for camaraderie, competition, transcendence, transferrable skill development, and a host of other positive outcomes. Succeeding in front of thousands of people brings a great sense of satisfaction and accomplishment. However, while college student-athletes’ successes are public, their failures also occur in front of people. In person and electronically. And those failures are commented on–often harshly–by anyone and everyone with a keyboard. A poor performance is broadcast widely. Friends see it in person, family members see the athlete react to the failure on TV, and strangers pass judgment and make snide comments on social media about the athlete and his/her abilities based on that performance.

So while being a collegiate student-athlete is an amazing opportunity, it also carries a great amount of stress. After all, these student-athletes are not robots. They are human beings who are playing a sport they love while they are getting their education. They think, they hope, they feel, they hurt. They are passing through the developmental stage when symptoms of many mental illnesses often arise. Yet they are expected to perform, and perform at a consistently high level. With these increased demands of participating in college athletics, student-athletes are at a greater risk for developing or experiencing mental health issues that can greatly impact their individual performance and subsequently their team outcomes. And that is where Sport and Performance Psychologists (SPP) are invaluable. SPP can help athletes manage these stressors, helping them compartmentalize the negative aspects of sport performance while also helping them maximize the positive aspects of sport participation.

Despite the potential for student-athletes to be subjected to increased risks to their mental health, college student-athletes are reported to utilize counseling or psychological services at rates lower than their non-athlete peers. Seeking help for mental health issues is stigmatized in the general population, but it is even more stigmatized among athletes. Furthermore, this dynamic is even more pronounced among male student-athletes who participate in contact sports. So when compared to their non-athlete student peers, when compared to female student-athletes, and even when compared to male student-athletes in non-contact sports, college football players tend to have more negative views about seeking professional psychological services. Researchers have found that attitudes or beliefs toward mental health is a major contributing factor in the likelihood of utilizing psychological services.

In summary, while all collegiate student-athletes face stressors, college football players face additional levels of stress, scrutiny, and pressure as they perform in their sport, given the visibility and popularity of this revenue-producing sport. When this reality is combined with the findings that college football players are less likely to utilize Sport and Performance Psychology services, it becomes increasingly important to better understand this dynamic so we can examine ways to access and provide services to these student-athletes within the unique context of college football. And understanding the contextual contributors to these beliefs is an important pathway.

While college football players’ attitudes and perceptions of mental health and usage of mental health services are strongly influenced by the complex student-athlete social environment (e.g. athletic trainers, academic advisors, athletic administration, teammates, friends, family), coaches play a primary role in the lives of these student-athletes. College football coaches set the social and cultural environment and play a primary role in determining the team’s overall attitude. Because the relationship between coach and player is considered one of the most significant relationships within sport, coaches were identified as primary gatekeepers in regard to attitudes and beliefs that most heavily influence mental health service utilization among their student-athletes. To investigate this dynamic and better understand the mental health and performance enhancement needs of college football players, we conducted a study that examined the attitudes of college football coaches about Sport and Performance Psychology services.

What We Found

In this qualitative empirical analysis, we interviewed nine coaches from college football programs across the United States. We interviewed one head coach and eight assistant coaches (e.g., offensive line, defensive line, wide receivers) who collectively had an average of 17.6 years (SD = 12.8) of coaching experience. All coaches had used aspects of Sport and Performance Psychology with their teams at some point during their careers and seven of the nine coaches currently had access to a SPP within their athletic department. Additionally, at the time of the study all coaches noted they have referred players to SPP in the past 6 months.

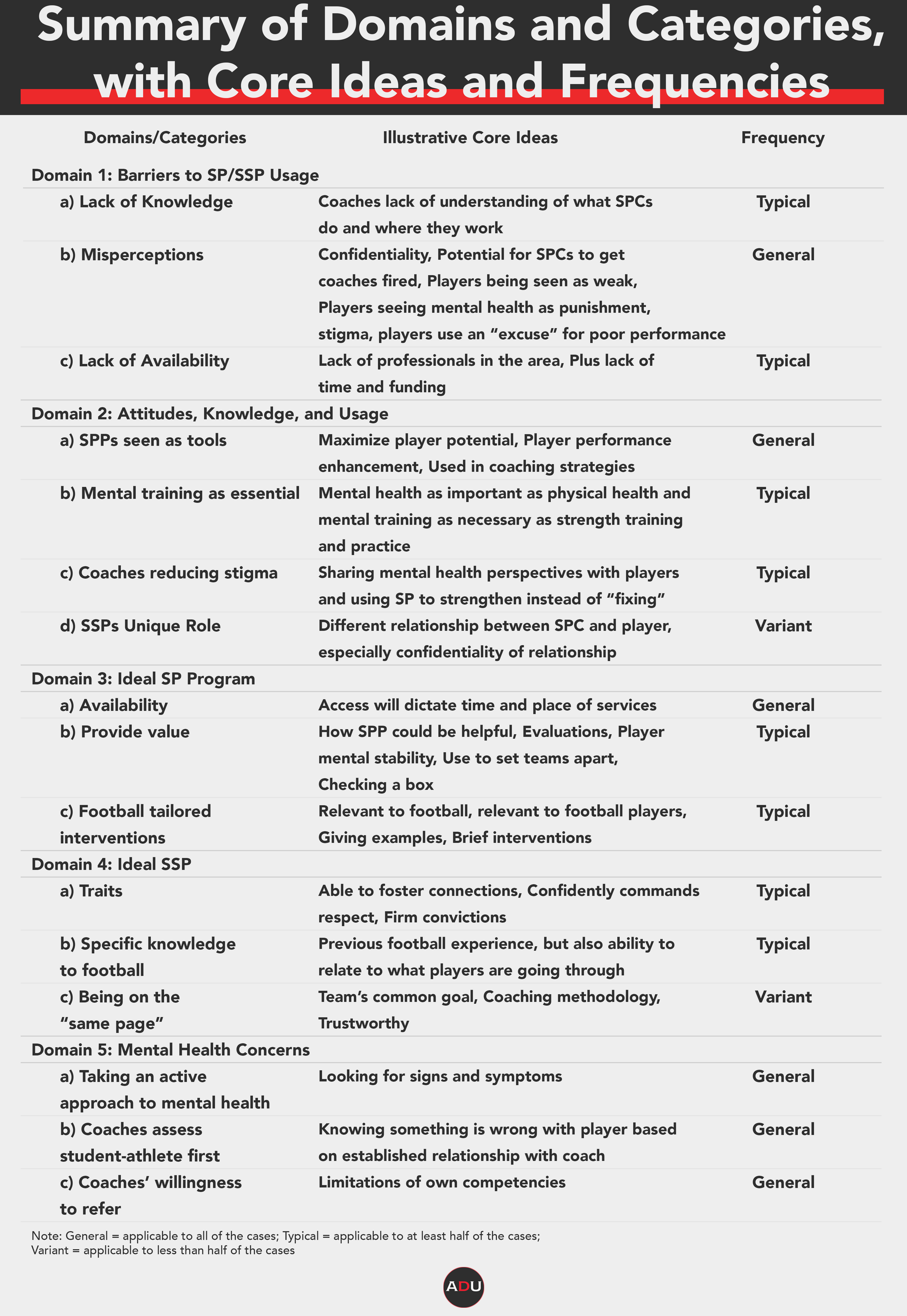

By employing a Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR) methodology, we distilled the responses of the coaches into Domains and Categories, which represented a structured categorization of attitudes and beliefs among the college coaches in the sample. The results of our analysis of the interview data produced five Domains: (a) Barriers to Sport Psychology Usage; (b) Attitudes, Knowledge, and Usage; (c) Coaches’ Ideal Sport Psychology Program, (d) Coaches’ Ideal SPP; and (e) Mental Health Concerns. Each of these Domains had a number of categories within its thematic structure, which can be found in the table below. Given the lack of knowledge about this dynamic, this qualitative study was an important exploratory effort to provide empirical evidence into how college football coaches view mental health and the potential impact of Sport and Performance Psychology services on the well-being of their student-athletes.

Results indicated that these college football coaches were able to articulate specific recommendations about ways to structure a Sport and Performance Psychology program, as well as ideal characteristics for the type of service provider they would want providing Sport and Performance Psychology services to their football players. Coaches also provided insight into their perception of barriers that exist for football programs to utilize Sport and Performance Psychology services, as well as their awareness of mental health concerns and how coaches could be resources to connecting their football players to services to help them address these concerns.

What Do These Findings Mean?

In regard to barriers, the coaches in our study discussed a lack of knowledge, a lack of availability, and misperceptions about what SPP do. Coaches had an awareness of the stigma associated with seeking mental training or for seeking help with mental health concerns; yet, coaches also indicated a lack of knowledge about the specific role that a SPP could play. These results highlighted some coaches’ lack of understanding of what SPP do, where SPP work, and their perception that their players also shared similarly unclear views.

Relatedly, coaches held acute misconceptions of the ethical bounds of confidentiality, a professional ethical obligation for SPP. Confidentiality—what is divulged in the office stays in the office (with some explicit exceptions to protect client safety)—is a cornerstone across fields of applied psychology and mental health provision. Confidentiality provides clients an assurance that they can be vulnerable and honest with the SPP about their mental health issues without judgement, retribution, or consequence. However, this dynamic is often not fully understood outside of those in the field. In this study, coaches reported that they were worried about being fired for what their players told the SPP, and they shared concerns about student-athlete information shared with SPP being used for gambling purposes. This result highlights the disconnect surrounding coaches’ understanding of confidentiality and their expectations for access to clinical information about their players.

Furthermore, college football programs maintain rigid and time-consuming schedules, so it is no surprise that coaches in this study perceived availability as a limitation to access. In response, SPP often hold non-traditional office hours to accommodate the hectic schedules of coaches and student-athletes. Coaches in this study also reported that they wanted a SPP available to the coaches, the team, and the student-athletes on a year-round basis. In addition, and perhaps most importantly, coaches stated they want an SPP present in team meetings, in coaches’ meetings, at practice, and in office hours. This finding is encouraging to our field because SPP have reported that being embedded within the team setting is a key contribution to their effectiveness—this presence helps combat the stigma of seeking professional help. However, within this embedded context, SPP must also set appropriate professional boundaries in order to ethically maintain professional guidelines (e.g., confidentiality) that are unique to SPP but often unfamiliar to coaches, administrators, and the general public.

These results also suggest that SPP working with college football teams need to be knowledgeable and skilled not only in mental health issues, but also in performance enhancement interventions, which represents the other side of the coin in Sport and Performance Psychology. By enhancing player performance through mental skills training, SPP can provide added value to coaches and teams, something the coaches in this study desired, with mental skills training tailored to fit the specific needs of football coaches and players. Likewise, coaches in this study indicated a preference to work with someone who had a similar sport-participation background (or sport-specific knowledge) because coaches in this study believed these SPP better understand the unique concerns, needs, and pressures that college football players face.

Finally, these results suggest that SPP working within the university athletic department or counseling centers could benefit from networking and increasing their visibility with coaching staffs. By doing so, these SPP could more effectively facilitate the process of helping coaches refer players whose mental health needs required professional psychological services. Coaches in this study indicated that they were actively looking for signs and symptoms of mental health concerns (e.g., depression, anxiety, adjustment disorder). These coaches also conveyed a willingness to refer players to SPP for those concerns. By building relationships with coaches, SPP could potentially increase coaches’ perceived confidence in Sport and Performance Psychology services as a necessary resource. In addition to building those relationships, SPP could provide consultation to coaches on ways to assist athletes who have received psychological evaluation with a subsequent diagnosis and treatment plan. Coaches supporting student-athletes during their treatment—while recognizing that there are limitations to the knowledge they are privy to in this process—enhances the likelihood that the student-athlete will be on a trajectory toward positive outcomes in enhancing their mental health and well-being, which will contribute to increases in their on-field performance.

Conclusion

As the field of Sport Psychology continues to expand and become more embedded within college athletic programs, it is necessary to assess ways that SPP can be effective in delivering services and accessing populations. Football represents a unique athletic subculture, one that has a demonstrable need for psychological services but is paradoxically a context that has been traditionally difficult to access. The findings of this study can provide athletic directors with coaches’ perspectives on their perceived constraints to utilizing Sport and Performance Psychology services, along with coaches’ vision for their ideal service framework with the ideal SPP characteristics. Utilizing these perspectives can help administrators better understand how to meet the specific needs of college football players, and how to position SPP to help meet those needs.

In summary, collegiate athletic departments value their expansive and diverse sport offerings (e.g., mantras such as Indiana University’s “24 Sports One Team”). However, this current COVID-19 disruption is illustrating that NCAA Division I college football brings unique value to athletic departments, universities, and to the landscape of our national sport identity. However, this comes at a cost because football’s high profile and ability for potential financial provision also can also subject college football players to heightened threats to their well-being and mental health. Athletic directors can utilize the result of this study to initiate and continue conversations with their coaches about the needs of their programs. These conversations can help administrators make decisions about incorporating Sport and Performance Psychology services that can validate their commitment to improving mental health and overall well-being of all college student-athletes, particularly the young men who play the most visible, demanding, and financially viable sport in their department.

Based on “Sport Psychology Utilization among College Football Coaches: Understanding College Football Coaches’ Attitudes about Sport Psychology,” published in Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics. Full text available.