The 2019 college football season is roughly 30 percent complete, and college athletes have settled into their routine of class, practice, film, weights, conditioning, eating, studying, and sleeping. What little free time exists is likely spent relaxing, meeting with friends, and scrolling through media.

As I have emphasized previously in this space, media is not limited to what we would consider the traditional mainstream media: newspapers, radio, magazines, and television. Today’s media environment also consists of social media outlets such as Twitter and Instagram, where college athletes have the ability, if they choose, to interact with anyone. It is this definition of “media” which I wish to explore further.

“Constant media attention to feed the appetite of the fans affects the football players’ view of their importance as human beings.” While that quote could easily be applied to college football players, it actually came from a 2011 International Journal of Sport Psychology research article by Elsa Kristiansen and Glyn Roberts about football (soccer) players in a Premier Division in Europe. While I am not attempting to compare student-athletes to elite, national-level soccer players from Europe, some parallels might be drawn between the two groups.

Consider this direct quote attributed to one of the soccer players interviewed by Kristiansen and Roberts (p. 353):

“The pressure is high in football… and that leads you to focus a lot on yourself, because you are convinced that you are part of something you believe is of major importance… that in turn makes you think that your performance is decisive both for the team and the action on the field… and for the health and happiness of people, so to speak.”

College athletes, particularly those in high-profile sports such as football and basketball, often find themselves in the media’s spotlight, especially in the smaller towns home to land-grant universities. These are towns such as Iowa City, State College, and pretty much any town that ends in -ville (Gainesville, Knoxville, Fayetteville, Starkville, etc.). The “health and happiness” of residents in such towns ebbs and flows based on athletic performances.

How athletes present themselves on social media has been the focus of numerous academic studies. Katie Lebel and Karen Danylchuk in 2012 were among the first to explore this area, studying how professional tennis players presented on Twitter. Andrea Guerin and Lauren Burch expanded to visual presentation in a 2016 article, exploring how Olympic athletes present on Instagram. I contributed to a 2017 study led by my former doctoral student Bo Li which looked specifically at student-athlete Twitter accounts and profile photos.

Equally as important are the high-profile case studies describing how athletes should NOT to behave on social media.

As a result, cottage industries developed in the early part of the decade as many athletic departments spent aggressively to bring in outside “media consultants” to present best practices to their athletes. Few athletic departments, however, have focused on the potential mental health consequences when athletes encounter negative media coverage, whether from the mainstream media or from misguided fandom. In fact, in a 2015 analysis of social media policies from 244 schools across all three NCAA divisions by Jimmy Sanderson and his colleagues, the overwhelming emphasis in such policies was on compliance and rule following. The authors recommended that future policies be more “reflexive” and involve athletes in the development process.

College football fans spend thousands of dollars each year on tickets, travel, foundation donations, tailgates and more to follow their favorite teams. Their “happiness” often hinges on whether those teams win or disappoint. Faced with underperformance, those same “fans” frequently extend their ire toward the college athletes directly responsible for their frustrations. This type of behavior is often referred to as “misguided fandom.”

Michigan State kicker Matt Coghlin was the focus of such misguided fandom after he missed a 47-yard field goal which would have tied the Spartans game with Arizona State on Sept. 14, 2019. Ignoring the fact that Coghlin had made a kick minutes before only to see it nullified by a penalty, MSU fans took to Twitter to express their frustration with the 22-year-old kicker.

Unless you are interested in NSFW rants from “fans,” it probably is not worth the time to search Twitter to find @matthewcoghlin posts in the immediate aftermath of the Sept. 14 game. Due to the high-pressure nature of the position, kickers often have the ability to determine a game’s outcome, making them the focal point of a win or a loss.

Following a high-profile missed field goal in the 2013 Iron Bowl, “fans” took to Twitter to blame Alabama kicker Cade Foster for the loss to Auburn. In what they coined “maladaptive parasocial interaction,” researchers Jimmy Sanderson and Carrie Truax published in a 2014 Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics article found evidence of four themes of this behavior directed at Foster: belittling, mocking, sarcasm, and threats.

In a 2012 research article in the International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, Kristiansen and her colleagues examined media stress coping strategies for elite soccer goalkeepers, a position somewhat analogous to a football kicker. Their research suggests athletes, when faced with extreme scrutiny from media or the public, use one of three strategies: seeking social support from their coach, family, and friends; avoiding media or the internet; and engaging in problem-focused approaches in which they fixate on the next task (game) at hand.

The researchers concluded that two factors, neither of which are present in college athletes, served as mechanisms to reduce stress from negative media coverage: age and experience. In the absence of age and experience, the social support system stood out as a primary way to assist athletes with media stress. “Coaches should recognize the importance of informational and emotional support when working with athletes who have to cope with negative media exposure,” (p. 305).

Social media consultant Kevin DeShazo, in his 2013 self-published book, iAthlete: Impacting Student-Athletes of a Digital Generation, advised four similar responses to college athletes who encounter extreme scrutiny deal: ignore it, retweet it, block the individual, or delete their account. Since most young people thrive off social media, the latter solution seems unlikely.

As of Sept. 17, Coghlin seems to have chosen to “ignore it” as he has not posted an original Tweet since May 2019, though he did retweet a post from the Spartan Radio Network promoting his appearance on a radio show two days prior to the Arizona State game.

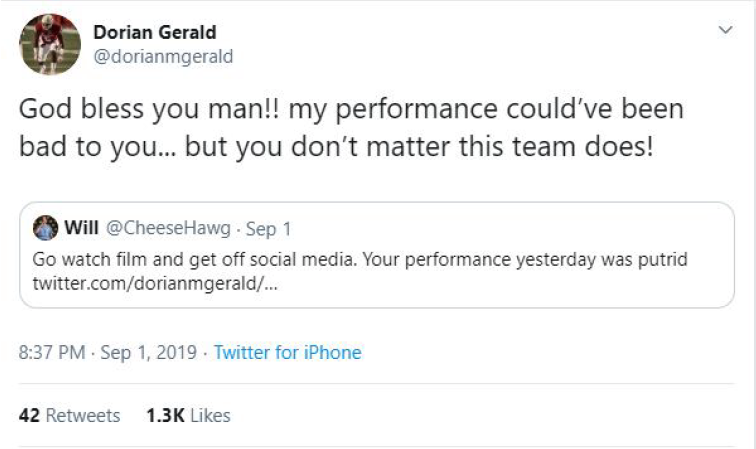

For an example of an athlete “retweeting it,” or at least engaging, we look to a Twitter exchange between an Arkansas Razorback football player and @CheeseHawg, presumably a “fan”, following the Hogs’ unexciting week one home win over FCS opponent Portland State on August 31, 2019.

Dorian Gerald was a starting senior defensive end in that game. The next day, at 6:51 pm, Gerald tweeted a photo of himself in action with text that read, “tough times don’t last, tough people do .. Shake back DG5️⃣🖤”. The photo shows Gerald celebrating at the end of a play. By all accounts, this Tweet is not out of the ordinary for a college football player. He even tagged a teammate who is also depicted in the photo. @CheeseHawg’s response was to tell Gerald to go watch film. Gerald opted to engage with the “fan”, replying within minutes and defending his performance and his team.

The next day, Sept. 2, Gerald Tweeted that his season was over and that he would be back next year “stronger than ever.” As the story unfolded that day, it was disclosed that Gerald had been hospitalized after the game for a strained artery, a serious injury that required blood thinners to reduced pressure on the artery. Gerald’s original Tweet probably had less to do with the outcome of the game, and more to do with the as-yet-undisclosed injury.

I sent an email to the Arkansas athletic public relations department here on campus Sept. 12 requesting the ability to ask Gerald a few questions. I could have used my academic position to email or contact Gerald directly, but I chose to follow athletic department policy and present myself as a reporter. My inquiry did not receive a response from the athletic department.

The reality is most college athletes are not made available to the media after a game. Communications staff often hand-select a few individuals, frequently the same players game after game, to speak to the media. As a result, college athletes do not have a forum other than social media by which to establish a personal brand or project an image of themselves.

I was hoping to understand why Gerald chose to engage. Did he think about potential ramifications to his personal brand? Why did he choose Twitter as a medium to disclose his injury? Understanding the motivations for athlete use of social media can help athletic departments make better decisions about the level of social media support they provide to athletes.

College athletes in the high-profile sports have to realize their actions in college have the potential to impact their future status. Writing in The Athletic on September 5, Joe Smith noted, “By the time they are drafted, the top prospects have played at least a season or two on national television in the NCAA, starring in March Madness or the College Football Playoff. Browns quarterback Baker Mayfield already had a cult following before he was a top pick, and it was the same with new Cardinals QB Kyler Murray.”

It makes sense, therefore, that college athletes present themselves to the media in a strategic manner which will allow them to leverage their abilities and enhance market value after college. A 2016 empirical study from Pawel Korzynski and Jordi Paniagua in Business Horizons, one of the top peer-reviewed business journals, recommended that “sports stars should pursue followers (on Twitter) and engage actively with them in order to maximize their contract value” (p. 189).

While college athletes might have an economic motive to maintain an active social media presence, particularly as mainstream media access to athletes may be shrinking, active engagement on social media carries potential risks to the athlete’s well-being. As more college athletic departments add sports psychologists and mental health counseling services to their portfolios of student-athlete development capabilities, the potential for how unaddressed negative media stress impacts mental health concerns for college athletes should not be overlooked.

This is not a new suggestion. Sanderson and Truax drew this conclusion in their 2014 paper on Cade Foster: “when college athletes do report being targets of this behavior, those who oversee athlete welfare along with other relevant personnel such as coaches, should discuss how to proceed in terms of using social media” (p. 344).