College football, a multi-billion-dollar sport for the 130 schools that play at the highest level, is unique in that it must recruit student-athletes, unlike high school or pro football. An entire multimillion-dollar industry has developed to provide recruiting ratings and team-specific information for rabid fans. The question in this study was “Do recruiting rankings matter?”

This study uses the 247Sports class ratings and team composite ratings to predict the future success of teams. The Sagarin ratings are used as a proxy for team success. The results indicate that recruiting success, as measured by the recruiting rankings, explains up to 36 percent of the variability of the Sagarin ratings. That is, 36 percent of a team success is the result of recruiting success and not other factors.

American college football is a sport that generates billions of dollars annually. It is also a rapidly growing sport. From 2004 to 2018, total football revenues for the schools playing college football at the highest division, the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS), grew from $1.6 billion to $4.6 billion (Office of Post-secondary Education, 2019). Universities are increasingly competing for a share of those revenues.

College football is also one of the highest attended sports in the world. It exceeds most professional leagues around the world, both in total and average attendance. For example, the Southeastern Conference (SEC), if counted as an independent league, would have the highest average attendance of any league in the world. The SEC’s 2014 average attendance of 77,694 (NCAA, 2014) exceeded the NFL’s average attendance of 68,776 (Solomon, 2015).

Several major businesses, including Rivals, Scout, ESPN and 247Sports, rate high school prospects numerically. Typically, these recruiting services assign a ranking, from two to five stars, to show the rating of the recruit. Individual player ratings can be aggregated to evaluate the quality of each school’s signing class. Each recruiting service publishes school recruiting rankings which are influenced by both the number and quality of recruits signed by the school. The rankings typically include a numerical value and a star rating. Despite the potential differences among the systems, they all have the same goal: to predict future “on the field” success for players.

Because of the growth of college football and the proliferation of the multi-million dollar recruiting media, the question continues to be asked, “Do recruiting rankings matter?” There are two opposing arguments on this question. There are the people that Miller (2011) termed “star-gazers” who believe that the rankings are predictive and teams with better recruits perform better than teams with lesser recruits. This argument’s mantra would be, “It’s not always about the x’s and o’s, but it’s about the Jimmy’s and Joes” (Miller, 2014). These proponents tend to give examples that show overall results using many years of data, while conceding that outliers can and do occur.

Some of the best examples for the benefits of recruiting rankings are given by sports writers analyzing years of data. Clay Travis shows that during 1996-2014, every national championship team, except for Oklahoma in 2000, had at least two top 10 recruiting classes in the four years before the title. So, he concludes that, “football success has followed recruiting success.” Others evaluate teams based on the blue-chip ratio: the number of five-star and four-star players divided by total players. One analysis concluded that every national championship team from 2005-2013 had a blue-chip ratio above 50%. That is, over half of the roster was composed of blue-chip recruits.

The opposing argument is that the ratings are not reliable and should be dismissed. The proponents of this side point to specific outliers as evidence that the recruiting rankings do not matter. The outlier examples are teams with lesser recruiting rankings that win big or a star college player who was lightly regarded as a high school player. Some also argue that the recruiting rankings are either worthless at best or a scam at worst and point to the phenomenon known as the “Bama bump,” which occurs when a player that commits to Alabama is then upgraded in the recruiting services (Connelly, 2015). This is seen as evidence of the recruiting services pandering to large and rabid fan bases for subscription revenues.

Both sides of the argument have interesting anecdotal evidence. However, answering the question accurately requires serious data analysis. Our paper analyzed the correlation between recruiting rankings and team success with a large dataset for all schools in the FBS. This study examined the question, “How effective are recruiting ratings in predicting future team success?”

Our paper differentiated itself from previous studies in several meaningful ways. First, we had a larger dataset than any of the other papers – including 17 years of data for every FBS school. Second, we used the 247 Composite Class Ratings to measure the quality of recruiting classes. The 247 Composite Class Ratings combine data from all four recruiting services into an overall score, thus reducing the potential randomness of focusing on ratings from a single recruiting service. Third, we used the new 247 Composite Team Ratings which no other paper has used. Fourth, we measured team performance with the Sagarin rankings, which are superior to other performance measures because it rates all schools using an unbiased algorithm based on several factors – including strength of schedule. Thus, the Sagarin ratings are a much better proxy for the quality of team performance than wins or winning percentage.

Previous studies used wins or winning percentage as the variable for football success. Using wins has a seductive appeal because it is easy to collect, verify, and understand. However, not all wins are equal. A win over a top 25 opponent is obviously more valuable than a win over a lesser ranked opponent. The problem inherent in using wins or winning percentages is that strength of schedule is ignored, and any win is good and any loss is bad.

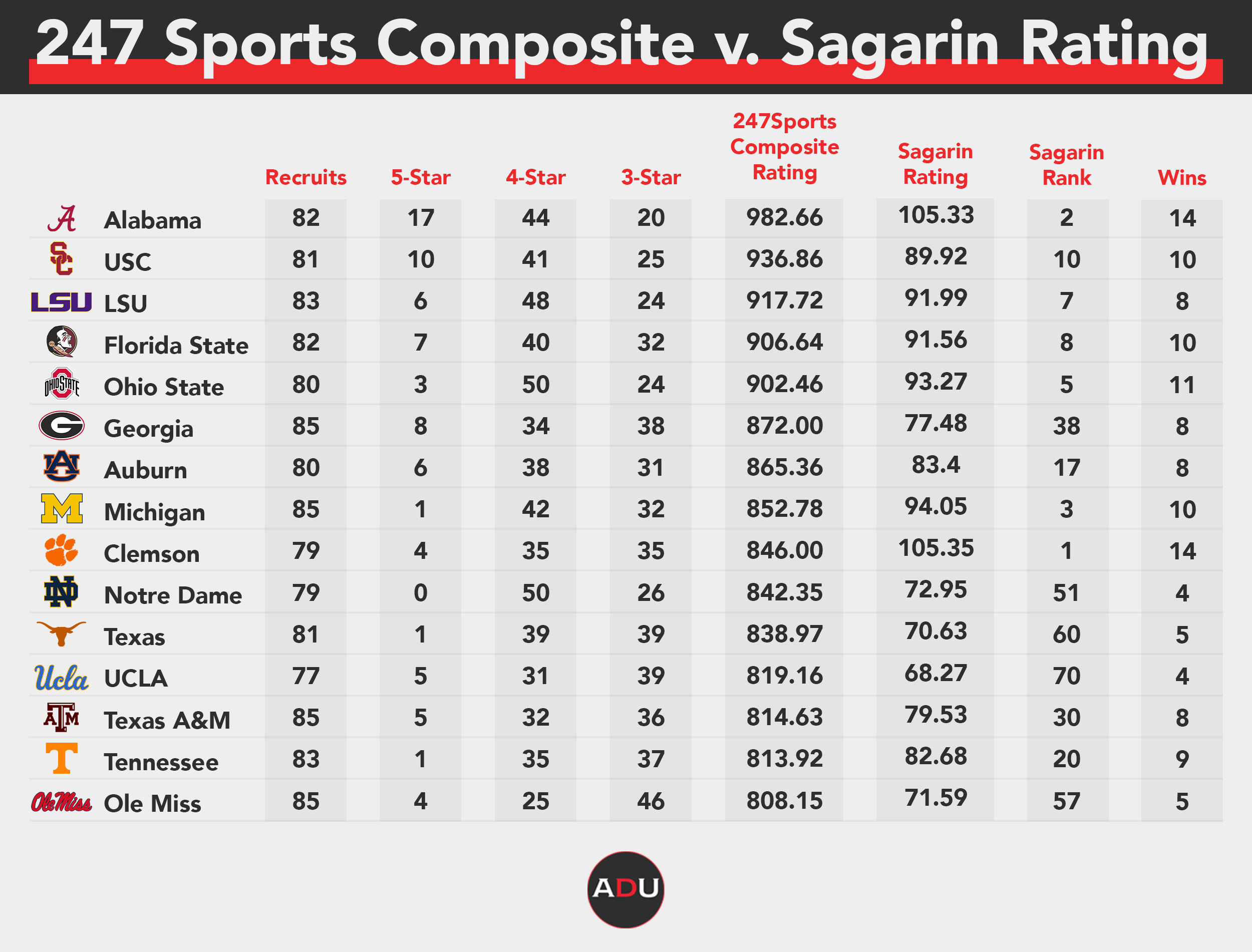

We compiled 247 Composite Rankings for the 2002–2018 recruiting classes and the Sagarin team rankings for 2005–2018. So, 17 years of recruiting data was used to predict 14 years of team performance. A team was composed of four to five years of recruiting classes. The table below provides a snapshot of the 2016 season and the relationship between the previous four years of recruiting classes and final Sagarin team rankings.

The following table shows the top 15 schools in 2016 according to 247Sports Composite Team Rating along with the school’s final 2016 Sagarin rating and rank plus wins. Alabama was the top rated school with 82 recruits from the previous four classes on its roster and a composite recruiting rating of 982.66.

The data analysis showed that recruiting ranking data plays a very important role in explaining the success of college football teams. The 247Sports ratings are good predictors of the final Sagarin ratings. The results indicated that up to 36 percent of the total variation in the Sagarin ratings was explained by the recruiting rankings. This indicated that the effort and expense of football recruiting is important to the health of the football program both in terms of wins and finances. Our results showed significance for each recruiting class in a given season, except the senior class which is likely explained, at least in part, by early entry into the NFL draft.

If a college football team is good, then it produces more wins, more tickets sold, and more revenues for the school. Athletic administrators concerned with how football performance impacts overall athletic department revenues are justified in spending resources on football recruiting if it improves a team’s overall recruiting ranking. Evidence from this study suggest that investment will return greater competitive success and, likely, increased football-related revenues.

The recruiting industry is based on the premise that rating high school recruits is meaningful and that higher rated classes and teams will provide more wins and more success. We find that, indeed, recruiting rankings do matter.