In partnership with USA Today we collected and analyzed employment agreements for assistant football coaches at public Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) colleges and universities (the, “Sample Set”). This article is primarily a graphic summary of significant economic data points and trends from the Sample Set coupled with a few observations regarding annual compensation, bonuses and mitigation provisions.

Summary: Fixed Annual Compensation and Bonus Potential

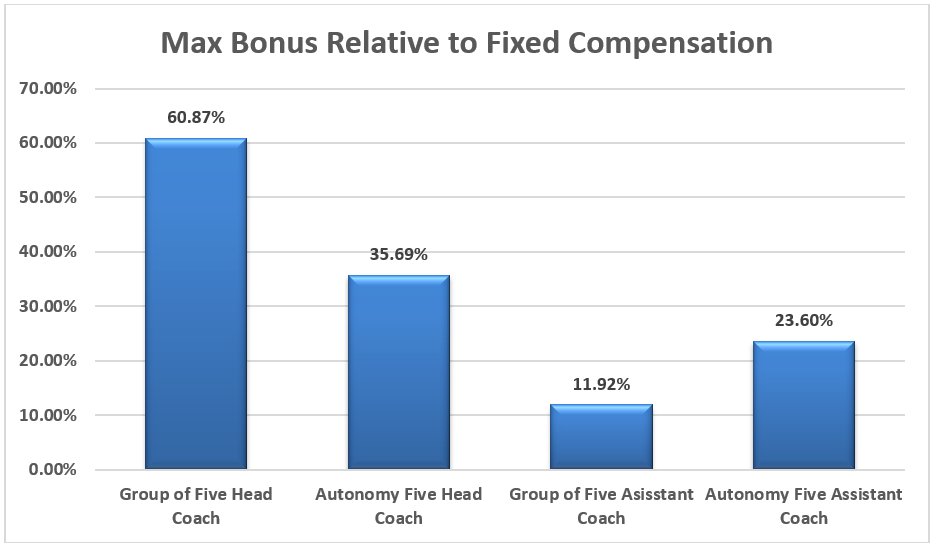

Bonus provisions present a possible trap for the unwary with respect to the new excise tax. There are 11 assistant coaches (including 3 coaching in the CFP National Championship Game) whose bonus potential may subject their university to the excise tax [see: How The New Excise Tax Impacts Coach Compensation]

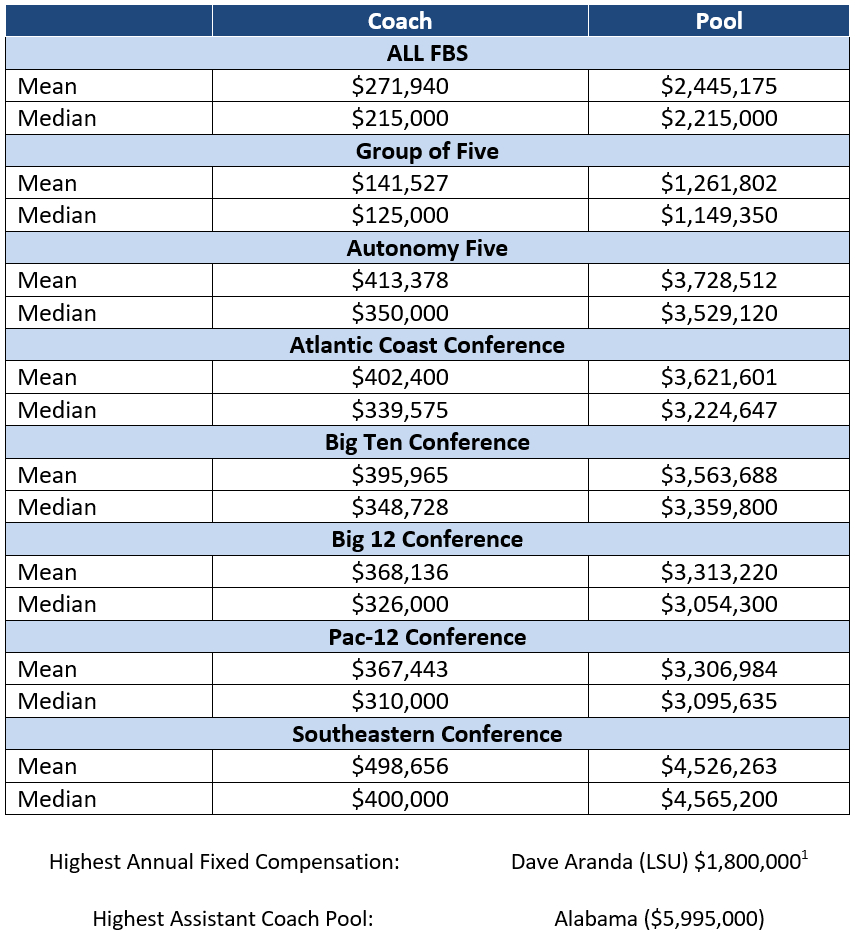

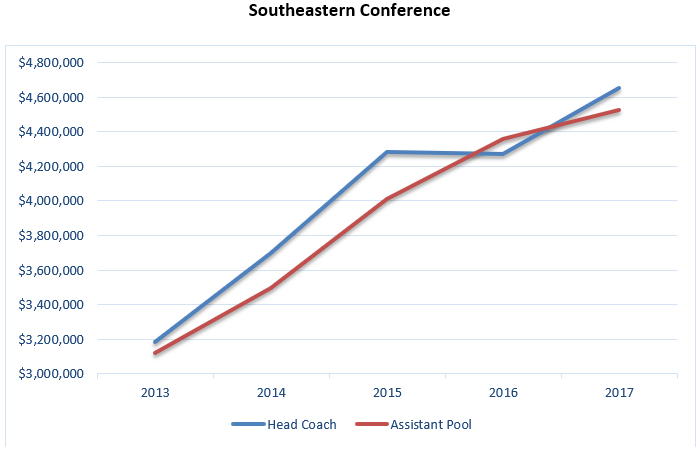

Head Coach Compensation Relative to Assistant Salary Pool

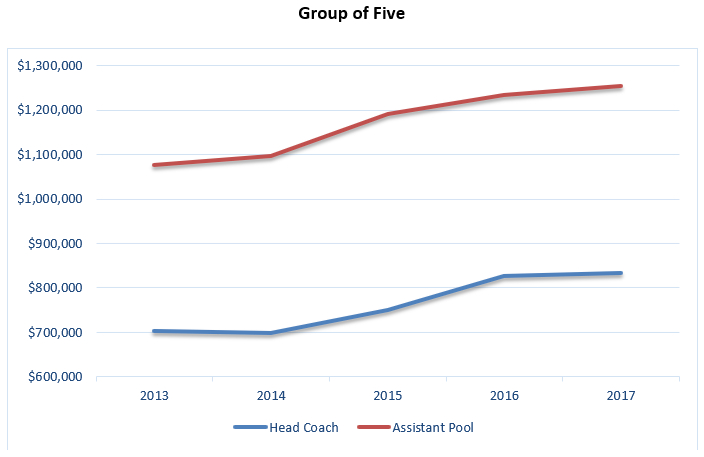

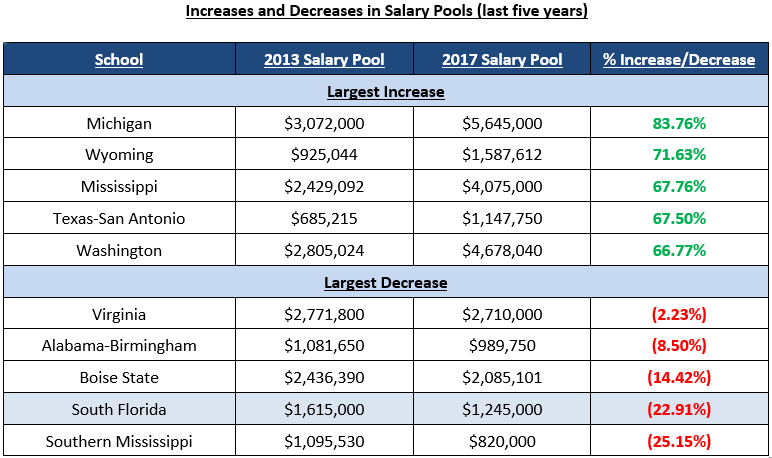

The gap between average head coach compensation and the average aggregate assistant coach salary pools at Group of Five institutions is likely to close, perhaps dramatically, as a result of (i) the addition of a 10th on-field assistant coach (effective January 9, 2018), and (ii) potential downward pressure on the compensation of those head coaches earning at the threshold of the new excise tax ($1,000,000).

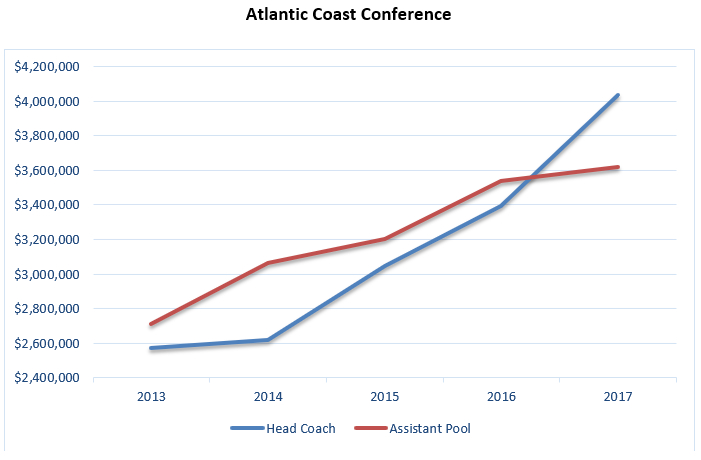

It is important to consider that there are five private schools in the ACC as well as the University of Pittsburgh, each of which claim an exception to open records laws. Consequently, the head football coach salaries that are available via informational tax returns are dated (at least one year and often two years old) and the sample set for ACC assistant coach salaries is disproportionately small, yet includes several highly-compensated, preeminent assistant coaches (Virginia Tech’s Bud Foster, Clemson’s Brent Venables, Tony Elliott and Jeff Scott, Louisville’s Peter Sirmon, Florida State’s Charles Kelly and Georgia Tech’s Ted Roof each earn $800,000, or more, annually). As a result, the difference in average head football coach compensation and average assistant salary pools is likely to be materially greater than depicted above.

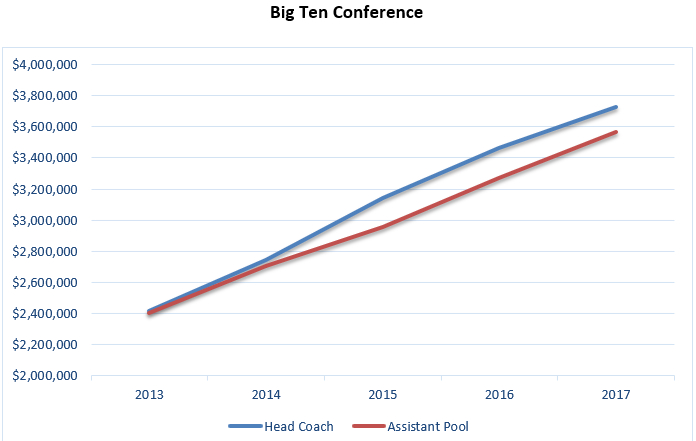

Head football coach compensation and assistant coach salary pools in the Big Ten have generally followed the same trends. Despite being nominally similar, and unlike the trends in the other Autonomy Five conferences, the average head coach compensation and assistant salary pool amounts in the Big Ten have not converged at any point over the last five seasons.

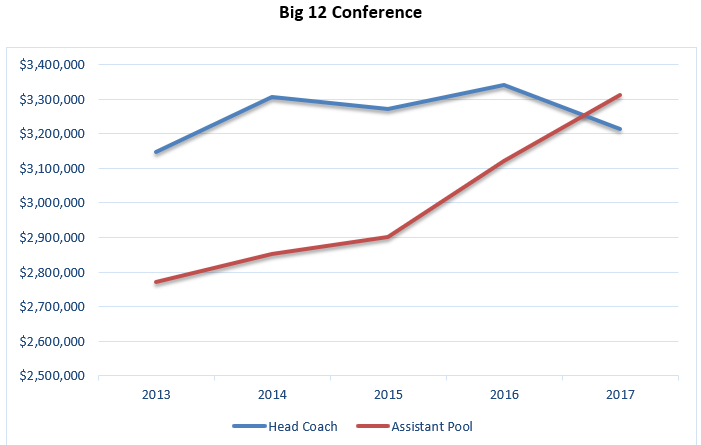

There has been a dramatic rise in Big 12 assistant coach salary pools over the last two seasons, and, as a result, the Big 12 is the only Autonomy Five conference in which the average salary pool exceeds the average head coach compensation. There are a number of factors that account for this circumstance, including the premiums placed on coaches to generate prolific offenses as well as the coaches challenged to defend against those offenses.

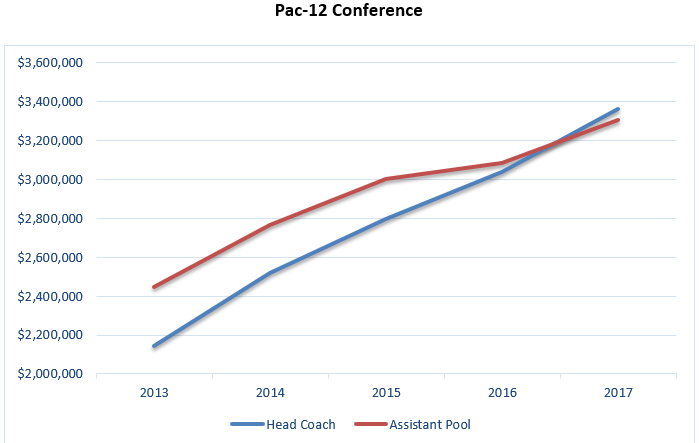

Similar to the Big Ten averages, Pac-12 head football coach compensation and assistant coach salary pools have remained consistent. But for a slight flattening of the assistant coach salary pools from 2015 to 2016, assistant coach salary pools would remain slightly larger than head coach compensation amounts in the Pac-12.

Assistant salary pools, as a percentage of head coach compensation, have decreased at 8 of 13 SEC institutions over the last five seasons (in top to bottom order of percentage decrease: Mississippi, Auburn, Alabama, Kentucky, Texas A&M, Mississippi State, Arkansas and Florida). These decreases have been buoyed, to some degree, by significant percentage increases at LSU (66.61%) and Missouri (68.05%).

Determining Annual Compensation and Adjustments

There are a host of factors that contribute to an assistant college football coach’s compensation: relevant, productive experience (e.g., college, professional, and level of each – FCS vs. FBS, Group of Five vs. Autonomy Five, CFL vs. NFL), history of performance (with an emphasis on recency), scope and uniqueness of skill set (e.g., recruiting prowess and teaching ability), position or title, market interest/leverage, etc. The foregoing coach-centric factors are, of course, in addition to the university employer’s interest in and financial wherewithal to pay the coach.

It can be challenging to accurately compare on-field performance of assistant coaches because of the difficulty in controlling for or normalizing innumerable variables, dependent and independent, that impact performance:

- Capacities and abilities of players coached;

- Competition / schedule;

- Injuries;

- Depth; and

- Support or challenges presented by the other side of the ball – e.g., a high-risk, up-tempo, no-huddle offense frequently places increased pressure (poor field position) and fatigue on the defense, etc.

Understandably, there is a correlation among compensation (annual salary and bonuses) and the overall performance of the team, the coach’s contributions (perceived or actual) to the success of a given phase or phases of the game (offense, defense and/or, to a lesser degree, special teams), that phase’s perceived contribution or discount to overall team performance (i.e., is the team considered an offensive or defensive juggernaut or liability?), the media attention focused on the team and phase performance and the recency of such performance. To be sure, statistical analysis is useful in evaluating and comparing performance. Statistical analysis alone, however, should be supplemented with reasonable, fact-based deductions that better paint the complete picture of a coach’s ability to recruit and develop student-athletes. For example, some coaches enjoy unique recruiting advantages provided by their institution (e.g., academic reputation, location, resources) while other coaches must overcome relative institutional challenges. Intangible factors are also critically important. Ask any head coach to list the top qualities coveted in an assistant coach and “trust” and “loyalty” will be at or near the top.

Our analysis of assistant football coaches over the past five years demonstrates a compensation bias in favor of overall team performance and recency. This is not surprising. And since the college football coaches’ labor market is a top-down, auction market (like most sports labor markets), increases at the top of the market tend to raise the fortunes of all coaches in the market, at least at the FBS level. It is debatable whether this escalation is sustainable. It appears undeniable, at least to us however, that universities can derive meaningful value from mining the market to identify coaches that out-perform their historical and current resources and represent equivalent (or perhaps even better) value than the over-valued coaches whose performance should otherwise be discounted as a result of relatively better or unique circumstances. Universities may fall into the trap of overestimating and overpaying coaches because they have (a) not identified equivalent or better alternatives in terms of talent, performance and fit; and (b) succumbed to pressure from a largely uninformed, albeit mostly well-intentioned, media and fan/donor base.

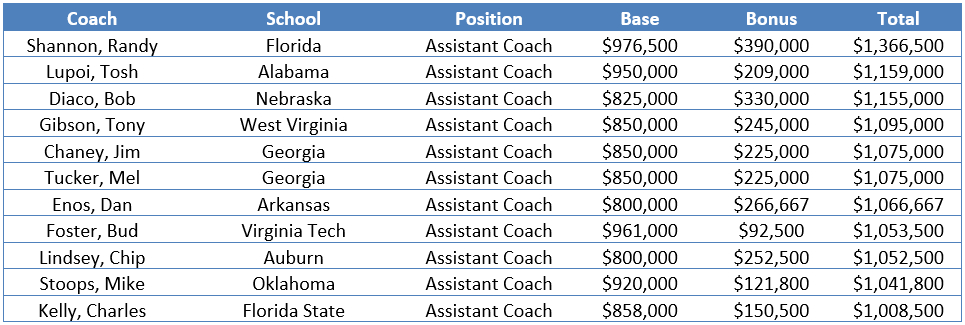

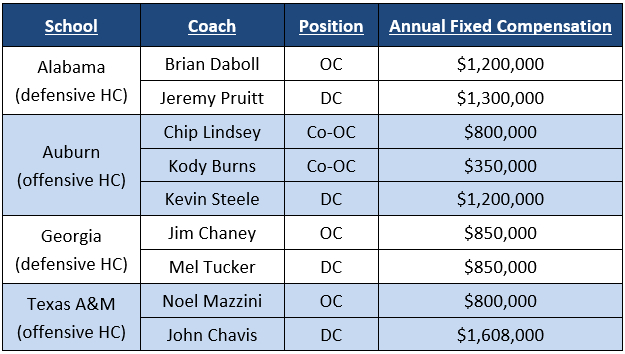

It stands to reason that a head coach with a given specialty – offense or defense – is more likely to be involved in coaching the assistant coaches and players on his “side of the ball”. It follows then that, other factors being relatively equal, compensation for coordinators will vary depending upon their responsibilities relative to their head coaches’ specialty. Our study of this issue reflects a general trend that defensive coordinators who work under an offensive specialist typically earn more than offensive coaches that work under a defensive specialist. Importantly, however, offensive coaches enjoy a decided advantage when it comes to receiving FBS head football coach jobs (incredibly, to date, 16 of the 18 head football coaches hired by FBS schools were apprenticed as offensive coaches). The following chart, based on 2017 compensation, provides examples from the SEC that support the assistant coach compensation relative to head coach specialty trend:

Additional examples supporting this trend include:

- Washington State Head Football coach Mike Leach owns a celebrated offensive mind. In 2017, Wazzu Defensive Coordinator Alex Grinch, a rising defensive coach who recently accepted the co-defensive coordinator position at Ohio State, earned $600,000 in annual compensation. In 2017 no Washington State assistant coach carried the offensive coordinator title and Coach Grinch’s 2017 annual compensation approximately doubled the next highest paid Wazzu assistant.

- University of Louisville Head Coach Bobby Petrino, a college quarterback and offensive whiz, guided the Cardinals to a third ranked FBS finish in total offense in 2017. U of L’s defensive coordinator Peter Sirmon earned annual compensation of $950,000 in 2017, a sum almost $350,000 more than the next highest paid U of L assistant coach.

- Oklahoma University and first year head coach Lincoln Riley led the FBS in total offense. Coach Riley, an offensive prodigy, was supported by defensive coordinator (and former head coach) Mike Stoops, who earned an annual salary of $920,000. Sensibly, the other assistant coaches on OU’s 2017 staff, including the three coaches that carried co-offensive coordinator and assistant head coach titles, earned annual compensation (exclusive of bonuses) at least $350,000 below Coach Stoops’ annual compensation.

Termination and Mitigation

Mitigation is a component of severance pay. In a previous ADU article, we summarized the doctrine of mitigation and provided an example of the University of Oregon’s well considered approach to using mitigation to limit its severance obligation in the context of its then current head football coach, Willie Taggart.

Our analysis of assistant football coach contracts revealed a trend, at least among Autonomy Five schools, that significantly reduces the Universities’ payout obligations in the event of the head coaches’ departures. There are a number of Autonomy Five schools, however, that do not differentiate payout amounts and mitigation requirements based on the departure of the head coach.

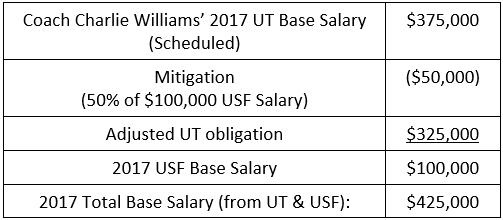

Consider the recent interplay between University of South Florida (USF) and University of Texas (UT) assistant coach contracts. Coach Strong brought several of his UT assistant coaches with him to USF: Coaches Burke, Gilbert, Jean-Mary, Mattox, Williams and strength and conditioning Coach Moorer. Each of these coaches was a party to an employment agreement with UT that included a mitigation provision that provided UT with a discount equal to “50% of the compensation received in the same corresponding year by Assistant Coach in his new position”. Notably, the UT contracts did not include “market check” and/ or “market adjustment” provisions. More importantly, the likelihood of a UT assistant coach securing a position at or near his UT salary in the circumstance where mitigation applies (i.e., being fired) was remote. Therefore, the mitigation formula created an incentive for the coach to accept below market compensation, which would likely come from another institution that already couldn’t afford to pay the coach as much as UT. This circumstance may be what the parties intended but few universities enjoy UT’s abundant resources. So, in the case of Coach Williams, he actually received a pay raise after getting fired from UT and landing at USF while USF saved a tidy sum during the period for which UT is obligated to pay him.

Coach Williams received a $50,000 raise in 2017 even though USF saved at least $100,000 by hiring him (Coach Williams’ USF compensation increases to $250,000 at the time UT’s on-going obligation expires). While each party – Coach Williams, USF and UT – benefitted by Coach Williams’ post-UT employment, UT’s relatively generous mitigation calculation is in stark contrast to the recent trend in mitigation provisions. For example, UCLA’s 2017 assistant football coaches’ contracts contain a clause wherein the assistant coaches agree to waive the right to, and UCLA shall have no obligation to pay, any severance payments if the departed coaches enter into an employment agreement that does not provide reasonable compensation consistent with the coaches’ experience for the positons accepted. These circumstances underscore the importance of a contract’s language separate and apart from its nominal economic terms.

[1] It has been reported that LSU and Assistant Coach Aranda recently agreed on a four-year, $10M contract that would make him the first college football assistant coach to earn $2M in annual salary.