USA Today (“USAT”) released its annual survey of head football coach compensation terms on Wednesday afternoon[2]. The USAT compensation database has become the go-to resource for salary information, in part, because it is current to the year in question (e.g., many coach contracts allow for annual, discretionary increases to salary and the USAT team goes to great length to update and verify these amounts on an annual basis) and because it follows a consistently-applied methodology[3] in distilling lengthy contracts to key economic terms.

One of the features of this year’s edition was a thorough analysis of the current amounts due to a coach should he be terminated without cause (for purposes of this article, “payouts”). The deviation between the lowest published amount (from $30,337 for Doug Martin to a staggering $40,000,000 to Dabo Swinney) provided fertile ground for discussion on the issue. The payout amounts were largely responsible for what USAT determined to be the “five deals that provide the least value for their respective schools.[4]” At the outset, it is important to clarify that a payout represents a potential, rather than a given or fixed, cost. Therefore, the value of a payout is more appropriately considered not by its potential cost to one party, but instead by the benefits derived by both parties to the contract, net of its likely cost.

Before jumping to any conclusion about the reasonableness of these amounts, it is important to consider the context and circumstances that drive many of the decisions about payouts. To provide such context, we reviewed the long-form contracts for the head football coaches at fifty[5] Power 5 institutions. From this group, we analyzed payout provisions[6] for out-years in each contract (as opposed to the current year terms shown in USAT).

When Are Payouts Triggered?

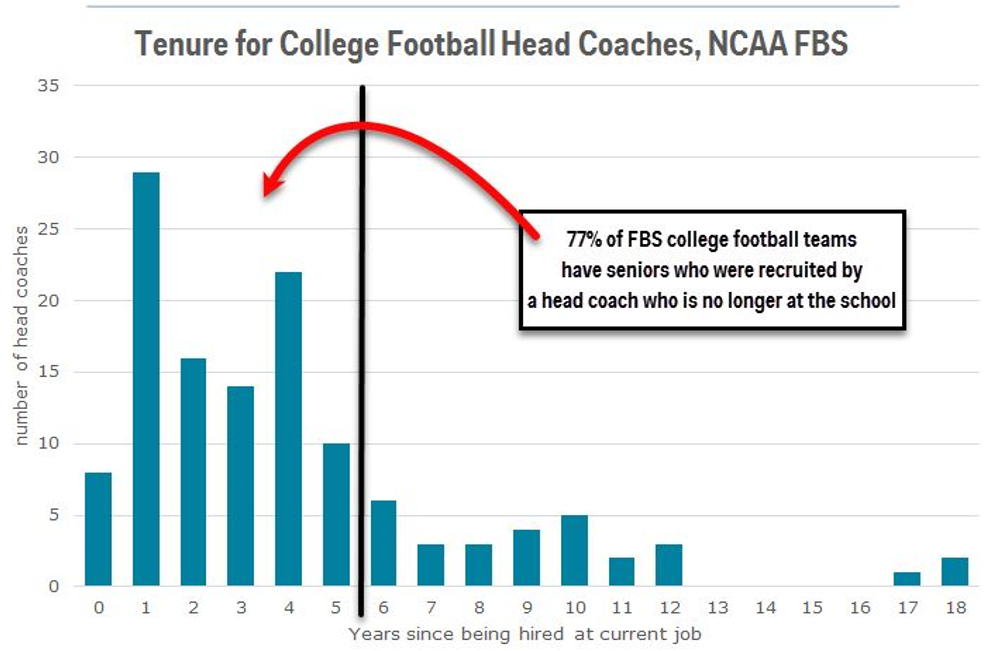

The USAT methodology views payouts applicable in the current year only. A better understanding of payouts, and their reasonableness relative to the market, is gained from analyzing payout amounts relative to the same[7] contract year.

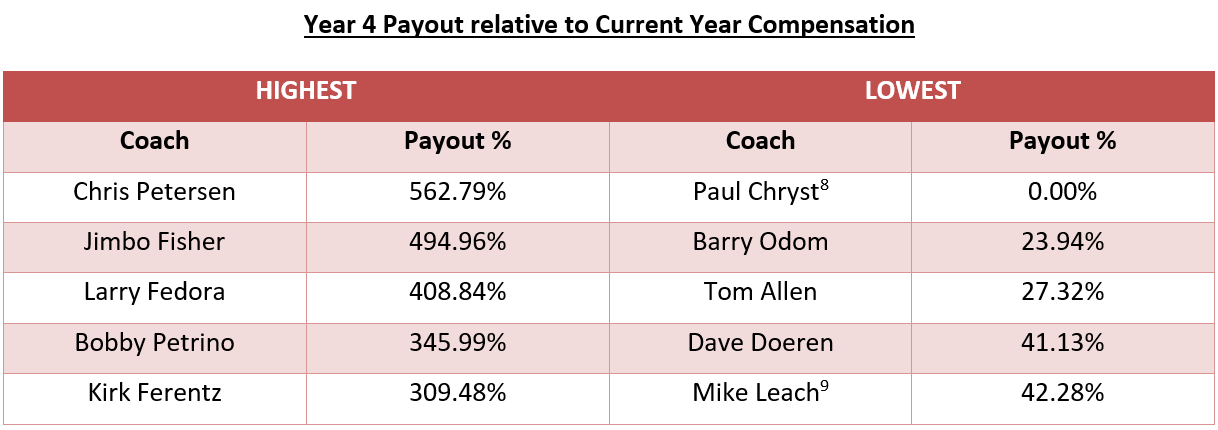

During the last three off-seasons, 41 schools initiated head coach changes. The average coach tenure at the time of termination was 4.85 years. Coaches were fired before their fourth year on the job in less than 20% of those circumstances. Consequently, the better metric for evaluating the payout market is what the contractual payout would be if the coach were terminated following his fourth season at the school. Among the reporting institutions, the average year 4 payout is $6,535,548 and the median is $4,333,334. These amounts equate to 158% and 136%, respectively, of reported current-year compensation.

Payout: Costs and Benefits.

Because payouts accompany the termination of a coach without cause, they concurrently represent a potential cost and a potential value to coaches and universities. From the university’s perspective, the primary consideration driving payout amounts is whether the value to the program in retaining the coach will be greater than the product of the payout multiplied by its likelihood.

Terminations prior to the start of a coach’s third season are extraordinarily rare. To wit, of the 41 terminated coaches in the above-referenced sample set, there were only 2 circumstances of a coach being terminated without cause prior to his third season. Those circumstances were similar and unique in that (a) each coach was promoted to the position from an interim role, (b) by an athletic director who was subsequently replaced, and (c) each held some relation to widely-condemned off-field issues at their school. However, coach tenure continues to creep downward, leading to speculation that some coaches may be on the “hot seat” after a mere two years.

In light of those data points, consider the following “hypothetical”:

- “Coach A” is a ~40 year old defensive coordinator in a conference where football “just means more” and has the opportunity to become the head coach at the school where he starred as a defensive back. Coach A signs a multi-year employment agreement which allows for termination after the 2nd year with a payout of $10,800,000.

- “Coach B” is a ~40 year old defensive coordinator in a conference where football “just means more” and has the opportunity to become the head coach at the school where he starred as a linebacker. Coach B signs a multi-year employment agreement which allows for termination after the 2nd year with a payout of $1,462,500.

If either coach were to struggle in year 2, which of the two athletic directors is more likely to face unreasonable demands from the school’s stakeholders (fans, boosters, student-athletes, coaches, athletics and university administrators)? If the opportunity cost of keeping a coach is perceived as being greater than the actual cost of terminating that coach, the stakeholders are more likely to demand the termination, no matter how unprecedented.

As head football coach tenures continue to trend downward, coaches are likely to demand and athletic directors are likely to accept large payout provisions as a shield from the often unreasonable demands of outsiders. A large payout early in the coach contract affords meaningful value to coaches and perhaps equates to recruiting success and on-field performance (a large payout offers greater assurance to current and prospective student-athletes that they are more likely to complete their collegiate career under a single coach) with no out-of-pocket cost to a school. Similarly, sought-after assistant coaches are intensely mindful of the job security of their head coaches or potential head coaches. Consequently, the prudent athletic director will balance the front-loaded payout structure in recognition that year 4 is, statistically, the prime evaluation year. A thoughtful payout structure aligns the expectations for the school, coach and stakeholders alike.

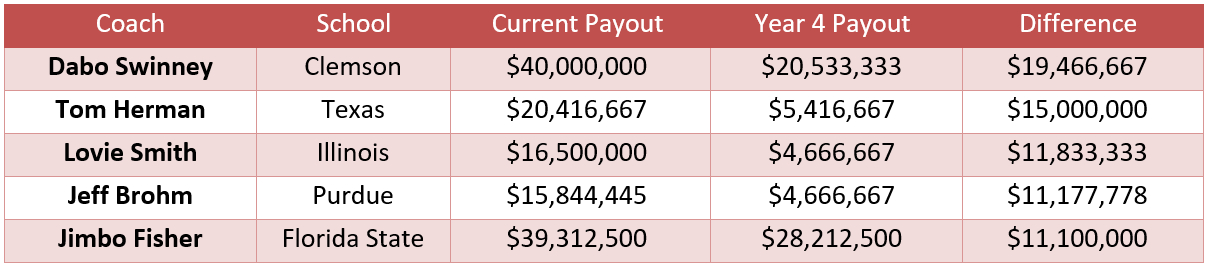

To this end, the following represents the largest difference between current payout and year-4 payout:

Discounts to Payouts: By Law and By Contract:

Most states laws invoke the mitigation of damages doctrine. Simply put, this doctrine imposes a duty on a person who has suffered damages to take reasonable action to avoid additional damages. In the context of a payout, the coach is the person that has suffered damages; the loss of his job without cause. Except in circumstances where doing so is impossible (e.g., disability) or highly impractical, most courts would require a fired coach to seek and secure other employment as a means to mitigate the University’s financial obligations under the contract. Thus, universities typically enjoy the benefits of mitigation even if the coach contract it negotiated is bereft of an express mitigation or offset provision. But because many universities are unsatisfied with the time, expense and uncertainty of a common law remedy, they negotiate express liquidated damages provisions that limit their payout exposure (30 of the 50 contracts in the sample set discussed herein include some variation of a mitigation/offset clause).

Willie Taggart’s employment contract with the University of Oregon is instructive in its consideration and treatment of important payout and mitigation issues. For example, Oregon’s payout obligations in the context of a termination without cause are limited in several ways:

- Defined Sum. Initially, the payout is limited to sixty percent (60%) of Coach Taggart’s Guaranteed Salary over the remainder of the term of the contract.

- Collateral Income. The contract expressly excludes liability for any collateral business opportunities or other benefits (e.g., unemployment compensation) resulting from activities such as camps, clinics, media appearances, broadcast talent fees, apparel, equipment or shoe contracts, consulting relationships or other income opportunities attendant to his position as the (then former) head football coach.

- Payout Period. The payout amount is paid on a monthly basis, as opposed to a lump sum over the scheduled term of the contract (the, “Payout Period”). Importantly, the duration and structure of the payout period is, of itself, a potential trap for the unwary as Internal Revenue Code Sections 409A and 457 treat payouts as deferred compensation, eligible for narrow, albeit complex, exceptions. This issue is frequently overlooked in this context, leaving coaches unknowingly subject to substantial penalties and/or accelerated tax consequences (and universities face corresponding withholding and reporting consequences).

- Mitigation Obligation. During the Payout Period, Coach Taggert is obligated to mitigate Oregon’s obligations by making reasonable, good faith and diligent efforts to obtain Comparable Employment, a broadly defined term in Coach Taggert’s contract.

- Offset. The University’s obligation shall be reduced by the monthly compensation (broadly defined) from Comparable or other employment.

- Market Check. If the monthly compensation from the new employment is not within an acceptable range of compensation as compared to terms produced from arms-length negotiations considering market-place factors, then the off-set amount shall be the median monthly compensation as determined from publically available sources in equivalent positions.

Effect on Assistant Coach Contracts. It is also becoming more common among FBS schools to reduce the payouts to its assistant football coaches to a sum less than the remaining compensation due under their contracts (usually stated in terms of a percentage of remaining salary or number of months of salary) in the event their head coach’s employment is terminated for any reason.

An aggregate reading of the foregoing reveals that the true cost of payout figures must be considered in context; the contract’s terms as well as the individual(s) involved and the employment market for those individuals at a given point in time can dramatically affect the true cost of the payout.

Conclusion:

Coach contracts represent one of many costs attendant to the successful operation of a college football program. Astute administrators, coaches and commentators recognize that coach contracts (and the myriad economic components contained therein) must be viewed in the context of a program’s global circumstances in order to assign value based on any one term.

____________________________________________________________

[1] Roger Denny & Bob Lattinville are co-chairs of the Spencer Fane LLP Collegiate Athletics Legal Team. Denny & Lattinville also collaborate with USA Today on the annual football coaches, men’s basketball coaches & athletic director salary databases as well as other athletics compensation databases which can be found on ADU. The pair can be found on Spencer Fane’s website.

[2] http://sports.usatoday.com/ncaa/salaries/

[3] http://sports.usatoday.com/2017/10/25/2017-ncaa-football-head-coach-salaries-methodology/

[5] Long-form contracts are not publicly available for: Baylor, Boston College, Duke, Miami, Mississippi, Mississippi State, Northwestern, Pittsburgh, Southern California, Stanford, Syracuse, TCU, Vanderbilt or Wake Forest.

[6] Payout amounts are determined as of December 1, 2017 of the year in question. Amounts do not take into account per-day pro-rating for a partial contract years. Longevity and/or retention payments were also not included in the calculated amounts.

[7] For each contract analyzed, the first contract year was determined as the most recent contract or amendment in which the term was extended.

[8] Coach Chryst entered into his original contract with the University of Wisconsin on December 19, 2014. The original contract provided for a payout amount determined as follows:

-$6,000,000 if separation occurs within the first year of Employment Agreement (12/18/14 – 1/31/16);

-$5,000,000 if separation occurs within the second year of Employment Agreement (2/1/16 – 1/31/17);

-$4,000,000 if separation occurs within the third year of Employment Agreement (2/1/17 – 1/31/18);

-$3,000,000 if separation occurs within the fourth year of Employment Agreement (2/1/18 – 1/31/19);

-$3,000,000 if separation occurs within the fifth year of Employment Agreement (2/1/19 – 1/31/20).

On February 1, 2016, the original contract was amended to add an additional year to the term of the contract. On February 1, 2017, the contract was again amended to add an additional year to the term. Neither amendment made any revision to the payout terms of the contract. Accordingly, the contract, as amended, contains no stated payout amount for a termination occurring during its final two contract years.

[9] Coach Leach’s, and others’, contract contains a rollover provision whereby the term of employment is automatically extended, unless either party provides notice stopping further extension before the extension becomes effective. For purposes of identifying contract years in this article, we have assumed, in each instance, that such notice was delivered at the outset of the current term. For example, if Washington State were to terminate Coach Leach’s employment, without having previously stopped the automatic extensions, it would owe a payout determined with reference for the then-remaining 4-5 year term, as opposed to the remaining 3 year term resulting from the assumption used in our methodology. Accordingly, the payout numbers calculated for this article are likely lower than the amount that would actually be payable by the school.