The University of Houston held a press conference on Thursday, August 25, 2016, to announce a $20 million gift from Tilman Fertitta, chair of the University of Houston System Board of Regents and of Billion Dollar Buyer fame, to transform the basketball arena. During the press conference coach Kelvin Sampson said it would give the Cougars, “an unbelievable competitive advantage.”

Coach Sampson was right. Since the gift, the Cougars have made an appearance in the Sweet 16 in each of the past five NCAA tournaments. For context before the gift, the program did not have a Sweet 16 appearance since 1984 or finish a season ranked in the Associated Press poll since 1983.

The gift by Fertitta illustrates a major shift in philanthropy: big gifts matter now more than ever. A single pivotal donation or a pair of significant gifts can mean the difference between a failed and successful capital campaign or fundraising year. Leadership gifts transform facilities and programs. Big gifts also create incredible momentum for athletic directors and their programs.

Fortunately, research on 33 of the largest gifts in college athletics history shows there is a clear and methodical path to pursue and secure them (disclaimer: the research does not include the Fertitta gift).

Philanthropy becomes hyper-concentrated

An important and significant shift in fundraising was recently highlighted in an article titled, “‘Dollars up, donors down’: More charity money is coming from the ultra-wealthy,” by CNBC’s Robert Frank. One of the key points of the article was that fundraisers “have to adapt to a highly top-heavy landscape for philanthropy, with fewer donors but bigger contributions on the line.”

The data backs Frank’s theory that big gifts hold greater significance than ever before. A booming trend in the reliance of larger gifts is clear. For example:

- Results from the annual Council for Advancement and Support of Education’s (CASE) Voluntary Support of Education (VSE) survey found that 95% of money raised in 2022 came from just 5% of all donors. In the context of philanthropy, the Pareto Principle, which asserts that approximately 80% of the funds come from 20% of donors, was accepted just 20 years ago. However, in the realm of higher education giving, this principle is now mostly outdated.

- In 2011, Giving USA: The Annual Report on Philanthropy defined a mega-gift as approximately $30 million and collectively these gifts totaled $2.73 billion. One decade later, the definition of a mega-gift increased to an astounding $450 million and remarkably those gifts accounted for $14.9 billion.

As the macro data has highlighted, philanthropists have begun to concentrate their influence and gifts, giving a dramatic rise in transformative gifts. Due to a confluence of factors in society and philanthropy, transformational gifts are expected to become more influential in the trajectory of college athletics.

Curiosity about the process to pursue and secure leadership gifts

My fascination with leadership gifts started when I was director of the POSSE at Oklahoma State University. In 2007 and 2008, I was able to observe the adeptness of fundraisers and generosity of donors, including gifts from Sherman Smith ($20 million), Malone and Amy Mitchell ($28.6 million) and Boone Pickens ($63 million, his second-largest gift to athletics).

As a young fundraiser, I was curious about the process that made these gifts a reality. Almost 15 years later, my curiosity led to the creation of a list of the largest documented gifts in the history of college athletics. This evolving compilation now includes 58 gifts (or gift commitments), each reaching the threshold of $20 million. What truly stands out? 32 of these momentous 58 gifts were made within the past five years: so many, so recently.

As the data shows, programs are more reliant on larger donations from a smaller number of wealthy donors; however, the process behind closing big gifts has always been somewhat mysterious, even to seasoned fundraisers. Despite effective transformative gift solicitations, there was insufficient data to develop a successful algorithm for fundraising strategies. Questions still lingered:

- Was success just because of luck and just a matter of being in the right place at the right time?

- Was success a result of a special, long-term relationship? With so much turnover in college athletics, is that even realistic for fundraisers?

- How can athletic directors, development officers, and university presidents most effectively influence the philanthropic process?

Analysis of the largest gifts in the history of college athletics

To answer these questions and codify a process to pursue and secure leadership gifts for both research analysts and fundraisers, I studied 33 of the 58 largest gifts in the history of college athletics.

Framework

Using Ben Porter’s Principal Gift Checklist as an instrument for the study, his 17 checklist items were analyzed in the 33 gifts. Porter’s research revealed that administrators and fundraisers should have a “green light” for a $5 million+ gift solicitation after about 12 of the 17 checklist items are present.

Donor Attributes (for research analyst professionals):

-

- Alumni status: The belief among fundraising professionals is that individuals, or their spouses, who are university graduates forge stronger connections with the institution.

- Known assets of $100 million or more: Generally, the rule of thumb is one must have at least $100 million in assets to make a gift of $5 million or more.

- Evidence of liquidity: A liquidity event such as a business or stock sale or inheritance is a good indicator that a prospect can make a substantial gift.

- Demonstrated seven-figure philanthropy to a charitable organization: Previous giving is an outstanding philanthropic indicator of future giving.

- Over the age of 60: As wealth builds and long-term financial standings have more clarity, donors are more willing to commit larger gifts.

- Regional proximity: The closer donors are to campus, the more they can participate in athletic events and board meetings, tour facilities, meet with staff, etc.

- Deep, long-term nondevelopment engagement: Porter describes “life connection” to analyze if the donor has/had children/grandchildren attend the university, if they are double-alum couple, season ticket holder, etc.

Cultivation Steps (influenced by development professionals):

- Established development officer relationship: Development officers have time to learn details and determine the philanthropic motivation of donors to help shape strategy.

- Campus visit: A campus visit can be inspiring, help recreate a stronger connection, and better understand the vision of the athletic director and other university leaders.

- Three or more visits with the director of athletics: Building trust takes time.

- High-level annual giving: Which signals confidence in the department and leadership.

- High-level board service: This can reconnect donors to the university, capture vital feedback, and learn of visionary plans.

- Meaningful engagement of key family stakeholders: Spouses and children are often part of the decision-making process for transformational gifts. Their buy-in can have an influence.

- First major gift (or test gift) of $500,000 or more: This is typically a path to build trust and credibility with donors. It also helps to focus philanthropic interest.

- Stellar execution of test gift: If a donor feels great about the impact of a gift, s/he is likely more inclined to give a larger gift. It is about trust building.

- Creative, customized stewardship of test gift: The department’s personalized, sincere gratitude motivates higher levels of giving.

- Prior meeting with university president: If the CEO of campus takes the time to cast a vision for the impact of a transformational gift, the donor is more likely to give.

Results

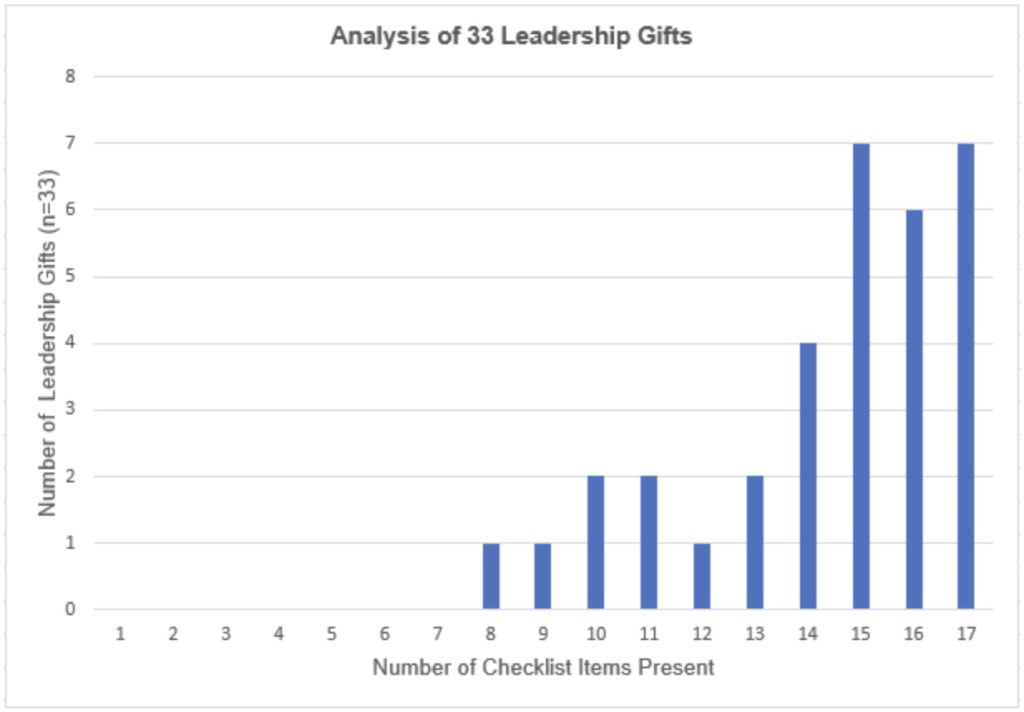

The 17 checklist items highlighted above were analyzed in 33 of the largest gifts in the history of college athletics; all 33 gifts were $20 million or more. An average of 14.3 of the 17 checklist items were present in the 33 gifts. This number is up from an average of 13.5 (of the 17) checklist items present in the initial study last year of 15 gifts. The expanded research has strengthened the idea that the checklist process is significant. The frequency of each checklist item can be found in the table below.

Given that the 33 gifts studied were at the $20 million+ level, surpassing Porter’s examination of gifts at $5 million+ level, it logically follows that a greater number of checklist items (14.3, to be precise) were present. In simpler terms, securing larger gifts necessitates cultivating a deeper relationship and ensuring that more boxes are eventually checked. The graph below displays the number of gifts that correspond with the number of checklist items present.

While this study reaffirms what most experienced fundraisers know – the pursuit of leadership gifts is a process that takes time and intentionality – it should also help to systemize the process.

Research analysts know seven crucial items to evaluate; and fundraisers know which ten items to focus their time on for cultivation and stewardship purposes.

There are no shortcuts to transformational gifts. As my mentor at the 12th Man Foundation, Stu Starner, taught me, “Daily processes – worked diligently – over a period of time – will inevitably achieve success.” Your athletic department’s fundraising success may only be one checked box away.

Summary and takeaways

The study, which gives rare insight into over half of the largest gifts in the history of college athletics, can serve as roadmap to plan and eventually secure transformational gifts.

Promising news for leaders in college athletics: the Wealth-X Billionaire Census 2020 examined the top interests, passions, and hobbies of billionaires and other wealthy individuals and found philanthropy and sports emerged as the two most prominent areas. Philanthropy and sports rated higher than areas such as politics, real estate, art, aviation, education, technology, outdoors, public speaking, writing, and even family. In the latest census, philanthropy and sports remain the top two for billionaires aged 50 or older. This data alone has tremendous, positive implications for the future of fundraising in college athletics.

Key takeaways for fundraising professionals:

- Giving has become less of a grassroots movement and more top-heavy. As the concentration of wealth continues, this trend should intensify.

- Modeling, research, cultivation, and stewardship should focus on the 17 checklist items, which lead to transformational outcomes. Since giving potential in fundraiser portfolios is not spread equally, development professionals should invest time in the “needle movers.” Typically, about 10% of a fundraiser’s portfolio can make a real difference. In short, to paraphrase John Wooden, do not confuse being busy with being productive.

- A “campaign of one” (one donor, one large gift) – as described within the advancement profession as a novel approach to fundraising – can have a greater return on investment than ten other major gifts combined, so focus time and effort accordingly. The Principal Gift Checklist, a proven methodology and visual reminder, will help to prioritize fundraising activities and time. Fundraising success occurs one checked box at a time.

- Leaders, often pressed for time, should be more intentional in the planning process to pursue and secure transformational gifts. For example, two of the top donors analyzed said in separate interviews they did not consider their leadership gift until athletic directors approached them with an opportunity to invest in the program at a higher level.

The late Boone Pickens, the largest donor in the history of college athletics via Oklahoma State University, would often say, “A fool with a plan can beat a genius with no plan.” Fundraisers should take note – big gifts matter more than ever – and plan accordingly.

Jason Penry has 20 years of experience in consulting for universities. Penry was the second-ever holder of the James W. Aston ’33 University Chair in Institutional Development, established in 1985, at Texas A&M University. Penry spent over a decade in university leadership as a chief advancement officer/vice president/vice chancellor at Arkansas State and Angelo State/Texas Tech System.