We reviewed all current forms of compensation for the athletic directors at National Collegiate Athletic Association member institutions of the Football Bowl Subdivision (“FBS”).[1] We analyzed these employment agreements and related documents (the, “Contracts”), which were obtained in partnership with USAToday, and created a sortable database of primary compensation (click here to view the FBS Athletic Director Database, the “Database”).

From the foregoing analysis, we respectfully submit the following economic takeaways, observations and suggestions:

1. Average Total Compensation and Bonus Availability

A. Total Compensation By Division

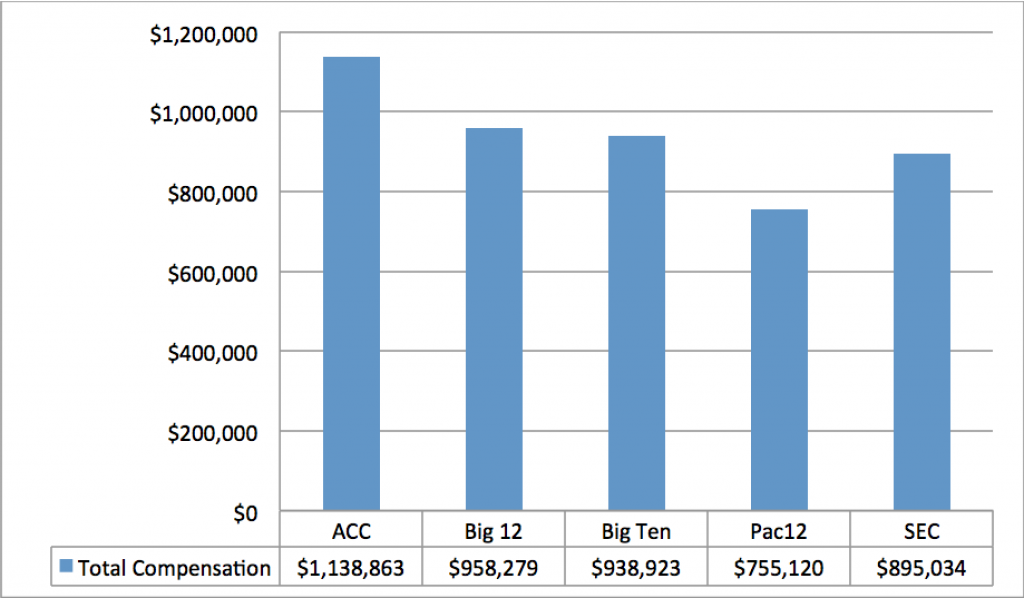

B. Total Compensation By Conference (Autonomy 5)[2]

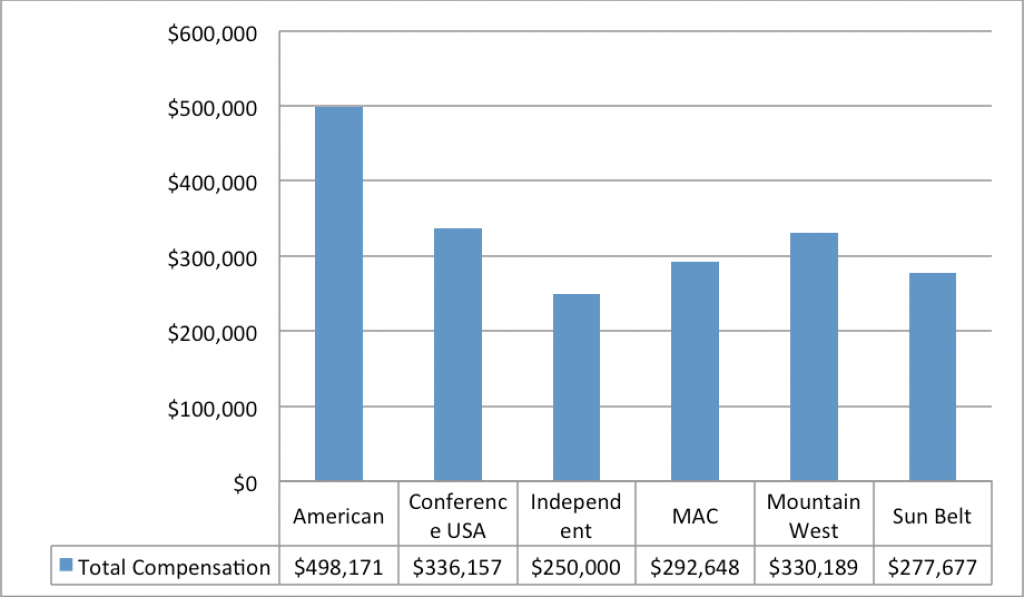

C. Total Compensation By Conference (Group of 5)

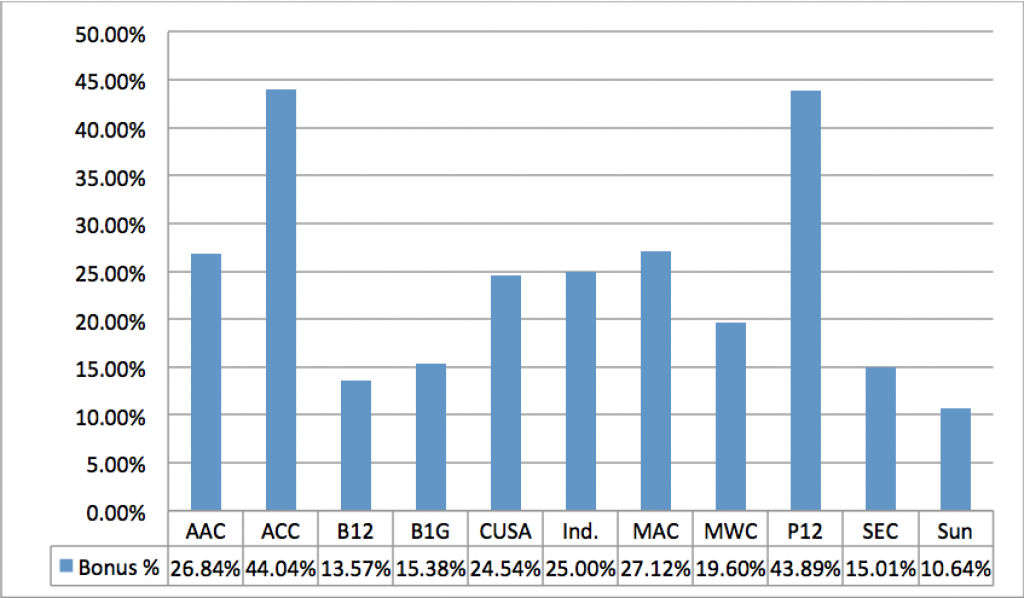

D. Maximum Bonus (as Percentage of Total Compensation)

There are 10[3] athletics directors with less than $1 million in total compensation who may become “Covered Employees” for purposes of the newly-enacted excise tax, as a result of bonuses earned: Ray Anderson, Scott Barnes, Mitch Barnhart, Rick George, Shane Lyons, Bill Moos, Dan Radakovich, Stan Wilcox, Scott Woodward and Debbie Yow. If an athletics director’s realistic bonus potential may trigger the excise tax, it may be smart business for universities to restructure the applicable employment agreement to reduce or remove bonus compensation in favor of: (a) increasing guaranteed compensation; (b) off-loading compensation obligations to third parties; and/or (c) establishing a split-dollar deferred compensation arrangement (See Section II of our previous ADU article regarding potential solutions to navigating the excise tax).

2. Job Changes

There have been 20 athletics director changes since our 2016-2017 AD compensation survey. As perhaps good logic would suggest, total compensation payable to the new, often yet unproven, athletics director decreased by $72,859, on average (we found an average year-over-year increase of $59,630 for sitting athletic directors). Meanwhile, when head football coach changes occur, there is often not a decrease in coach compensation (0.14% average increase with respect to 2017/2018 coach changes).

3. Payouts/Buyouts

Payouts are the sums owed by universities to athletics directors when the universities terminate athletics directors’ employment agreement without cause (as “cause” is defined in the athletics director’s employment agreements). Buyouts are the sums owed by the athletics directors to their universities when the athletics directors terminate their employment agreements without “cause”.

A. Ratio of Payouts to Buyouts.

From our analysis of athletics directors’ contracts we determined that the current average ratio of payouts to buyouts in the sample set is slightly greater than 3:1 (exclusive of the potential application and effects of mitigation). This ratio typically decreases as the employment agreements draw closer to their expiration. In some instances, particularly where the payout and buyout are based on different criteria (e.g., a payout calculated on remaining base salary through the end of the Term and a buyout established pursuant to prescribed payment schedule), buyouts can exceed payouts in the latter years of athletics directors’ employment agreements. For successful, veteran athletics directors – read: those with leverage – evaluating extensions to their employment agreements, consideration should be given to substituting a buyout (the “stick” approach”) with a retention bonus or similar longevity incentive (the “carrot” approach).

B. Relevant Financial Considerations.

There are numerous factors that support a 3:1 payout to buyout ratio. Importantly, unless a third party (e.g., future employer) satisfies the athletics directors’ buyout obligations (and resulting income tax consequences, if any), athletics directors receive payouts and pay buyouts with after-tax money; the worst of both worlds from an income tax perspective. Moreover, in most cases, the athletic directors’ employment agreements afford universities a discount in the form of mitigation obligations that typically impose a dollar for dollar off-set of the payout from active income earned by the athletics directors during the employment agreements’ remaining terms. In a few instances, mitigation provisions impose a complete offset of the former universities’ payout obligations immediately upon the athletics directors securing other employment at any time during the term of their prior employment agreement. Mitigation obligations imposed on the athletics directors have the practical effect of reducing, oftentimes materially, the payout to buyout ratio. And obviously, except in the rarest circumstances, universities’ financial means are exponentially greater than the athletics directors they employ.

C. A Commonly Overlooked Income Tax Issue.

Approximately half of the athletics directors’ employment agreements in the sample set failed to fully and/or properly account for the Internal Revenue Code’s (the “Code”) application to payouts, a form of deferred compensation. Following is a typical example of the issue, the potential consequences and the remedies applicable to payouts that represent deferred compensation under the Code.

Code Sections 409A and 457(f)

The American Jobs Creation Act of 2004 made sweeping changes to the federal income tax treatment of deferred compensation arrangements through the enactment of Section 409A of the Code. Section 409A provides three criteria for the avoidance of current income inclusion, and other potential penalties, on account of such a deferred compensation arrangement:

1. The amounts deferred must be payable only upon one of the following events: separation from service, a specific date or time, death, disability, change of control, or unforeseeable emergency;

2. The arrangement may not allow acceleration of a payment schedule (with some exceptions provided under the corresponding Treasury Regulations); and

3. Any initial election to defer payment must be made prior to the beginning of that tax year in question.

The consequences for failure to comply with Section 409A are severe. If a deferred compensation arrangement fails to meet the requirements described above, then there are three adverse consequences:

1. All deferred compensation under the arrangement is includible in the participant’s gross income at the later of (a) the date when the amounts are no longer subject to a substantial risk of forfeiture (at the time of termination), or (b) the date on which a Section 409A violation occurs (i.e., when the compensation is not paid in accordance with the plan);

2. The employee is subject to a penalty equal to 20% on such deferred compensation; and

3. The employee is subject to paying interest on the underpayment amount (the tax on the amount added to the employee’s gross income that became immediately due but was not paid).

There is another section of the Code which may impose similar consequences. Governmental and tax-exempt employers (other than churches and most church-related organizations) are also subject to accelerated income inclusion under Section 457 of the Code. Section 457(f) of the Code is based on similar principals of constructive receipt and substantial risk of forfeiture , and generally taxes the present value of deferred amounts on the date they are no longer subject to a substantial risk of forfeiture.

Fortunately for those that are mindful of these consequences, there are two commonly used exemptions to avoid these consequences:

• Short-term Deferrals. Section 409A does not apply if the deferred compensation must, in all circumstances, be paid no more than the first two and one-half months after the close of the tax year in which it ceases to be subject to a substantial risk of forfeiture. Further, the inclusion in income of deferred compensation that is taxed in the current year under Code Section 457(f) is treated as a payment for purposes of the short-term deferral rule. As a result, any “short-term deferral” that is exempt from Code Section 409A will always be a “short-term deferral” that is exempt from Code Section 457(f). However, the inverse is not necessarily true given that the definition of “substantial risk of forfeiture” under Code Section 409A is narrower than the definition under Code Section 457(f).

• Separation Pay Plans. Section 409A also does not apply to payments upon an involuntary separation from service that (1) do not exceed the lesser of two times the lesser of employee’s base salary at the end of the year before the year of termination, or the Code Section 401(a)(17) limit on compensation under a qualified retirement plan (currently $275,000), and (2) are payable by the end of the second year following the year of termination. Code Section 457(f) also provides for a separation pay plan exemption, but the Section 457(f) exemption does not limit the amount payable by reference to the 401(a)(17) limit. As a result, a separation pay plan that is exempt from 409A (i.e., separation pay due to involuntary separation from service or participation in a window program) should also be exempt from 457(f) (as a “bona fide severance pay plan”), but not necessarily vice versa.

The foregoing exemptions can be used in tandem to shield the payout payments from acceleration and the taxes and penalties imposed thereon.

An Illustrative Example

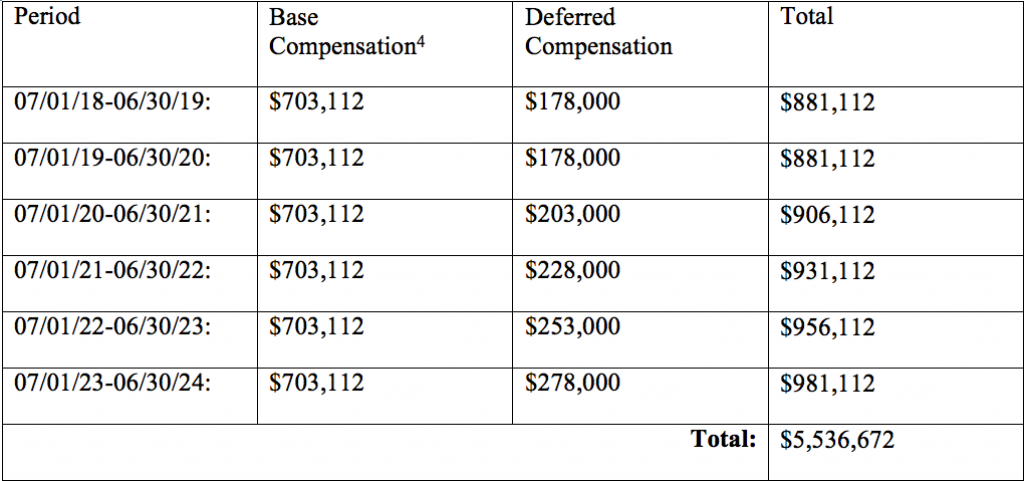

On December 1, 2016, Iowa State entered into an Amended and Restated Employment Agreement with its accomplished Athletics Director Jamie Pollard (the, “Contract”). The new Contract extended the term of AD Pollard’s employment to June 30, 2024 and provided him increased compensation, now totaling $868,112.

The Contract provides for the following in the event that Iowa State terminates AD Pollard’s employment, without cause:

“The parties specifically agree that University may terminate this Agreement without cause upon 30 days’ notice, and that upon such termination, University shall pay Pollard the amounts provided in Paragraph V(6)(a).”

The referenced Paragraph V(6)(a) provides that:

“University will be required to pay to Pollard an amount equal to the base and deferred compensation Pollard would have received for the remaining term of this Agreement provided under Paragraphs I, II and III. The payments shall be paid in equal monthly installments prorated over the remaining term of this Agreement.”

This payout is not conditioned upon the signing of a release, compliance with a noncompetition restriction, or any other action or circumstance.

Without suggesting that there is any reason why AD Pollard would be terminated without cause, assume that the University exercises its right of termination on July 1, 2018. In that hypothetical, the University would owe AD Pollard the following amounts:

This payout provision seems relatively innocuous. However, in this hypothetical, one may be surprised to learn of the significant adverse tax consequences associated with the termination.

Consequences to AD Pollard

The Contract is not, on its face, non-compliant with Section 409A. However, there is some ambiguity regarding the actual date of payment of the deferred compensation. The Contract is silent as to either party’s ability to accelerate the payment schedule. [Notably, many of the contracts reviewed include phrases such as “, or as the parties may otherwise agree” or similar language to describe the payment schedule attendant to the payout. Such a provision would theoretically allow the acceleration of the payment schedule and may unwittingly subject the arrangement to the adverse consequence described below.] While silence does not cause a failure of 409A compliance, any actual deviation in a payment date would violate 409A in operation. As such, additional specificity as to actual dates of payment, coupled with an explicit prohibition of acceleration or deferral, would be preferred. Assuming that Iowa State paid the payout amounts at the times scheduled (i.e., as long as the “deferred compensation plan” complies with Code Section 409A in form and operation), AD Pollard would likely avoid the early taxation, interest and penalties under Section 409A.

With respect to the consequences of Code Section 457(f), AD Pollard may not be as fortunate. The payout payments to AD Pollard prior to March 15, 2019 would be exempt from the coverage of 457(f) under the short-term deferral exception. Depending on the payment date, those amounts would be approximately $660,834. Those amounts would then be taxable in the years paid ($440,556 in 2018 and $220,278 in 2019).

Because the remaining payout payments would exceed two times AD Pollard’s base salary, he would not benefit from the Separation Pay Plan exemption and the present value of those amounts would be accelerated into AD Pollard’s 2018 income. The present value of the Section 457(f) accelerated payout payments that would be includible in AD Pollard’s 2018 income would be approximately $4,422,588. Assuming a combined federal and state effective tax rate of 40%, AD Pollard could have a tax consequence in the year of termination on the paid and accelerated portions of the payout equal of $1,945,258. Given that he would have only received approximately $660,834 in payout payments in accordance with the contract schedule, this could pose a significant problem for AD Pollard.

Consequences to Iowa State

In the course of negotiating payout provisions in coach and athletic director contracts, many administrators and their counsel mistakenly believe that the tax consequences to the employee have no effect on the employing institution. That’s incorrect.

While the consequences under Sections 409A and 457 of the Code would mostly fall on AD Pollard, Iowa State would be subject to corresponding penalties for (i) failure to withhold and pay federal employment taxes, and (ii) failure to withhold federal, state or local income taxes on account of the nearly $4.5 million of income accelerated into the year of termination.

The costlier consequence to Iowa State would derive from the application of the new excise tax under Section 4960 of the Code. While many consider the excise tax applicable only to certain employees making more than $1,000,000, the foregoing example is a clear illustration of a potential trap for the unwary. Section 4960(a)(2) of the Code imposes a 21% excise tax on “excess parachute payments” paid by applicable tax exempt organizations. The excise tax applies if the total present value of all parachute payments exceeds 3x the base amount, and the tax imposed is based on all excess parachute payments (i.e., parachute payment amounts exceeding 1x the base amount)[5]. The definition of remuneration for determining the amount of the parachute payment explicitly includes “amounts required to be included in gross income under section 457(f).[6]“ The present value of the payout would be approximately $5,119,034. The base amount is the average annualized compensation includible in the covered employee’s gross income for the five taxable years ending before the date of the employee’s separation from employment. For purposes of this hypothetical, we’ve calculated the base amount relative to AD Pollard as $679,165. Because the parachute payment exceeds three times the base amount, the payout would be subject to the excise tax under Section 4960(a)(2) and would result in a tax consequence of approximately $932,372 [($5,119,034-$679,165)*21%] to Iowa State.

As shown above, failure to properly consider and address the application of Sections 409A and 457 of the Code can have immense consequences to the employer and the service-provider alike.

_________________________

[1] Unlike the market for college coaches, there is not a traditional hiring period for college athletic directors. Consequently, the awarding, termination and administration of their Contracts, including adjustments to the duration and compensation prescribed by those Contracts, occurs throughout the calendar year. Thus, total compensation for college athletic directors is typically more difficult to normalize at any given time relative to compensation for college coaches. An independent methodology (described in the Database) was consistently applied to the analysis of each Contract in order to normalize the economic data derived therefrom and enhance its comparative utility.

[2] Notre Dame included in Atlantic Coast Conference.

[3] The same would have held true for Michael Williams (Cal), Mark Hollis (Michigan State) and Chris Hill (Utah).

[4] This amount reflects AD Pollard’s current base compensation. The contract provides for annual increases of 2%, followed by an increase to $725,000 on 7/1/19 and by $25,000 per year thereafter. However, those increases are “subject to a determination that Pollard’s performance has been satisfactory” and have been disregarded for purposes of this example.

[5] Code § 4960(c)(5)(A)

[6] Code § 4960(c)(3)(A)