Management of personal finances can be challenging for athletes who are juggling roles of student and athlete, and multiple sources of money with different stipulations for usage. This responsibility can take an emotional toll on students and could be ultimately detrimental to their well-being. Financial education can give students what they need to change behavior. Limited research suggests that athletes with more financial knowledge are more confident with money management and decision-making, but they tend to have less knowledge than non-athlete students. Athletes would benefit from financial education early in their college enrollment, enhanced with financial workshops and counseling tailored to them.

With athletes able to profit from their name, image, and likeness, it is critical that they have access to financial education that is relevant to their current situation. According to NIL Network, 26 states have signed into law legislation that permits athletes to earn compensation from their own name, image, and likeness. Congress also has seen several bills introduced related to athlete compensation. In October 2020, the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) passed an amendment to its amateur code that permitted athletes to profit from NIL and allows its athletes to mention their intercollegiate athletic participation during promotional activities and appearances. Like scholarships or tax refunds, receiving large amounts of income at one point in time to be budgeted over the course of several months requires discipline and knowledge of future expenses. Given that a very low percentage of college athletes “go pro,” financial education can strengthen their financial future.

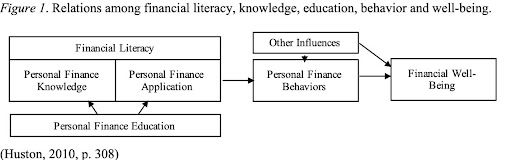

Financial literacy requires knowledge and the confidence to use that knowledge to make financial decisions (see Figure 1). Sources of financial knowledge, particularly for college students, vary widely and could include formal coursework, parental socialization, or financial counseling.

Together, financial knowledge and application are components of financial literacy, and developed through personal finance education. Financial literacy then influences financial behaviors along with other influences such as culture, economy, and personality characteristics. Financial behaviors impact one’s overall financial well-being.

Many college students are learning how to manage money for the first time and may not have a support system to ask questions about financial decisions as they navigate learning new skills. The combination of increased knowledge with the opportunity to gain confidence through its application is important in addressing financial literacy. The perceived ability to control one’s destiny is often referred to as locus of control. Internally motivated individuals believe that their actions determine personal outcomes, whereas externally motivated individuals are more likely to believe that personal outcomes are the result of chance or luck (external locus of control has been shown to be the most important predictor of poor financial behaviors). Gen Z athletes’ overconfidence increases their internal locus of control and has been linked to risky financial behaviors.

Through a 2018 NCAA Innovations in Research and Practice Grant, we gathered information on athletes’ subjective and objective financial knowledge, application of financial knowledge, and preferred modes of receiving financial education. Data were collected from two institutions in the same Power 5 conference, the results of which were published in the Journal of Athlete Development and Experience.

Participants were asked to rank their interest in financial literacy on a scale of 1 (not at all interested) to 10 (very interested). The average ranking was 7.3. Several participants were interested in investing and familiar with apps and platforms like Acorns, Robinhood, Mint, and exeq. All of the athletes interviewed suggested that they would benefit from financial education and literacy.

Subjective financial knowledge was measured through several methods. About a third of the athletes surveyed had received financial education in high school, 60% had not, and the rest (6.8%) did not remember. At college orientation, 19% received financial education, 65% did not, and 16% did not remember. Only 9% had ever met with a financial counselor. Senior exit interviews incorporated questions about financial knowledge and behaviors to gauge where athletes were at the time of graduation/exhausting eligibility. Most interview participants expressed a lack of knowledge in financial literacy. There were a wide range of responses when the athletes were asked how comfortable they were with managing their finances after college.

The pre- and post-tests that flanked financial literacy modules in a summer bridge program and first-year experience course contained three common objective financial knowledge items. For question 1, a scenario in which student-athletes were asked to assess how interest on a $100 savings account would work, 68% got the question correct both on the pre- and post-test from all respondents. From the matching paired responses, 61% got the question correct on both the pre- and post-test, 24% got the question incorrect on the pre- and post-test, 7% got the question incorrect on the pre-test and correct on the post-test, and 7% got the question correct on the pre-test but incorrect on the post-test.

For question 2, which built on question 1 by incorporating inflation and purchasing power, 59% of respondents answered correctly on the pre-test, whereas only 41% answered the item correctly on the post-test. From the matching paired responses, 37% got the question correct on both the pre- and post-test, 37% got the question incorrect on both the pre- and post-test, 5% got the question incorrect on the pre-test and correct on the post-test, and 22% got the question correct on the pre-test but incorrect on the post-test.

For question 3, which explored the rate of return on stock purchases versus stock mutual funds, 46% got the question correct on the pre-test, while only 29% got the question correct on the post-test. From the matching paired responses, 24% answered correctly on both the pre- and post-test, 49% answered incorrectly on both the pre- and post-test, 5% got the item incorrect on the pre-test and correct on the post-test, and 22% got the item correct on the pre-test but incorrect on the post-test. These results show that students may have the knowledge but struggle to apply it, and there are concerns with their retention of information.

All of the athletes who were interviewed had at least one bank account, whether checking or savings, and many had both types of accounts. About 21% of survey respondents followed a monthly budget, and the majority (92%) of those followed through on spending outlined in their budgets. Most athletes interviewed did not consistently track their spending. When asked how much of monthly income is left at the end of the month, 23% reported “usually nothing,” 47.5% reported “usually a little,” and 29.5% reported “usually a lot.” The top expenses athletes are responsible for included food for 78%, fuel/gasoline for 53%, housing for 48%, utility bills for 25%, cell phone charges for 24%, vehicle insurance for 14%, and car loan payments for 10%.

The majority of athletes (90% of respondents) do not share their funds. Over 60% purposefully saved money each month, 15% did not, and 24% saved some months but not every month. When asked about emergency funds, most athletes did not have one or considered parents to be the source of emergency support. Many were unfamiliar with what a credit score is and how it affects them.

Food (78%) and rent (48%) topped the priority list for athletes. Students self-reported their spending over a one-month period, providing the amount spent within the nine categories of food, transportation, entertainment, housing, personal care, school, insurance, debt, and family/friends. Students spent less than $100 on average in each category over the one-month period. At both institutions, athletes spent most often in the categories of food and transportation, even though athletic departments may offer meals to athletes regularly. Similarly, the availability of increased transportation options both on-campus and off-campus should allow students to feel less of a need to spend on gas, car maintenance, or services such as Uber.

Our survey asked athletes how they would like to receive financial education. Every option received significant interest, including: watch videos, get tips via text message, attend a workshop just for athletes, meet with a peer counselor, read a book, learn it as part of a class, and through an app on your phone. Like other Gen Z students, athletes prefer multiple modes of financial education. In focus groups, no participants knew about the available NCAA video modules on financial literacy. Overwhelmingly, athletes preferred one-on-one personal financial counseling because it is catered to their specific needs, with a professional counselor rather than a peer. They also preferred to have group meetings in the athletic facilities for convenience. The preferred formats for financial education that the athletes interviewed mentioned were one-on-one meetings with student-athlete development staff, one-on-one meeting with a financial counselor, guest speaker/workshop for athletes, in-person course for credit, online course for credit, and a combination of a class and one-on-one meetings. Thus, there is not one optimal way to provide financial education to athletes, and multiple options should be explored by athletic departments as they consider available resources.

If institutions offer peer counseling, we recommend that training include information about the experiences of college athletes, so peer counselors are able to address their specific needs. Institutions should offer peer or professional financial counseling to athletes in athletic facilities and during times outside of normal 8-5 business hours. Due to their difficult schedules preventing athletes from accessing campus resources during typical business hours, peer counseling could be offered during study hall/tutoring times. If athletes have required study hall hours or student-athlete development sessions, the athletic department can work with peer financial counselors so the athletes who take advantage of services get credit for this opportunity.

If a “Money 101” course is offered at your institution, athletes should consider taking it as an elective option, if degree applicable. If a course like this is not offered, but athletes enroll in a first-year experience or transition course, this content could be condensed into a module or within summer bridge programming. The facilitator should tailor some content specifically for athletes, like requesting video clips from the institution’s athlete alumni with their financial literacy tips and experiences with life after sport. We have heard about professional athletes that mismanage their money, but many student-athletes and generally college students may think to themselves, “that won’t be me.” Real examples move athletes to evaluate their own situation.

Programs to enhance athletes’ financial literacy can typically be implemented at no cost. Many athletic departments have a financial corporate partnership and should take advantage. Invite the sponsor to have workshops for individuals, team, by class standing. Corporate partners are very enthusiastic and willing to come talk with athletes about budgeting, establishing credit, and planning financially for their future. This is a way for departments to provide financial education to students without spending additional funds. Many programs do not have student-athlete development staff or programming because of financial or staff size limitations, so this is an option without additional costs.

Conversations during summer bridge programming help athletes prepare to budget and responsibly manage their first scholarship checks. We suggest inviting a financial representative once a month around the time rent is due to help athletes budget for the month, allowing them to stop by and talk if they have questions, which could also be designed as a virtual “financial office hours” session. This could be when students complete the monthly spending log to understand their habits, needs, and wants. Coordinators who offer student-athlete development programs might consider having students complete the log again after the first semester to see if financial behavior has changed, encouraging students to apply financial knowledge and money management skills learned. This is another retention strategy for financial knowledge.

If bringing in a financial planner is not feasible, invite athlete alumni from the financial industry, current or professional athletes, or other fields. to share tips with students. They can give a perspective on budgeting and saving, and how it looked during and when they left college. These visits could be recorded, with short clips put on a YouTube channel for students to view later. Athletes will also benefit from accounting workshops. Athletic departments should bring in an accountant or partner with an accounting firm to provide athletes information about taxes and filing, since NIL income is subject to taxes.

Having financial simulations where they can utilize real world examples such as buying a house, car, clothes, food, and childcare (if they have children) can be a good way for athletes to apply and expand subjective financial knowledge. Remember to make it engaging. Find a fun interactive game to play, like Financial Football, a free financial game that combines financial knowledge with a video game involving NFL teams. Athletes’ engaging with financial counselors and fun activities like Financial Football will help students retain information they learned in classes and workshops. We also recommend that the Student-Athlete Advisory Committee has a student in the Treasurer role to learn how to budget and allocate the organization’s funds, modeling application of financial knowledge.

Many athletic departments have formed partnerships for companies designed to help athletes develop and build their individual brands. These resources provide athletes support in creating a marketable brand to capitalize on NIL opportunities. Though this may not be available to athletes at institutions outside of Division I, athletic departments might consider partnering with the academic programs in Marketing, Graphic Design, or Communication on their campuses and offer engagement between students in these programs and athletes. Brand development by peers is likely to be a mutually beneficial experience for academic programs, their students, and athletes, plus stay fresh and relevant for Gen Z consumers.

As athletes gain access to revenue-generating vehicles, it will become imperative for athletic departments to augment existing financial literacy programs. In fact, offering financial literacy classes and educational programming should be the floor. NIL-related agreements between athletes and private companies will present complicated matters related to state contract law, state, and federal tax codes among other areas. Universities would be well-served to provide athletes with access to legal representation and contract analysts who are separate from the athletic departments. This bifurcation would safeguard against potential conflicts of interest that may arise between coaches, administrators, and athletes. Athletic departments must prepare their students for long-term financial well-being and NIL opportunities.